Modest Mouse’s album, The Moon and Antarctica, was already five years old when I first heard it—as a file shared over AOL Instant Messenger. When I downloaded the file inside my dorm room at the beginning of sophomore year of college, I didn’t know it would become the soundtrack to some of the most delicious and productive solitude of my life.

How to Defend Your MFA: The Hairdresser’s Line of Inquiry

I was having my hair cut recently in my home town in the English countryside, enjoying a break from the perpetual motion machine of New York. Not a terribly interesting thing in itself, but when you’re in the summer bridging your two-year MFA program, with your thesis relentlessly vying for your attention, any moments in which you can sit and relax are worth noting. So there I was, happily trapped at the mercy of the hairdresser, trying to look uninteresting enough to avoid conversation, when:

“So what do you do?” she asks innocently.

Spirit in the City: Lauren Nixon on Creative Places and Spiritual Practice

Lauren Nixon is a Food and Wellness Educator who guides people in cultivating spirit-filled lives through self-care practices and real, healthy food. She writes about healthy food for BlackGirlinOm. Her writing has also appeared in MindBodyGreen, Elephant Journal, Cooking Light Magazine’s Simmer, Boil Blog and others.

I spoke to Lauren during a time of exciting transition

Unleashing the Unconscious: Poetry, Place and Neuroscience in the Art of Kuma Kitsune

Above: Detail from Kitsune’s A Walk Through the Looking Glass.

Kuma Kitsune is a mixed-media artist and photographer living in Portland, OR. Her work incorporates a diversity of materials, such as fabric, projection film, tiny shreds of paper — and, in her most recent installment, other people’s poetry. More of her work can be seen here.

E. D. Watson: Your current work, A Walk Through the Looking Glass, is an assemblage of twenty-four individual pieces, titled with fragments of poetry produced by Hafiz, Ray Bradbury, Mary Oliver, Rimbaud and Lewis Carroll, which form a corresponding poem. Viewers are then invited to re-position the works and create their own poem from the new arrangement of the titles. Can you talk a little bit about how literature influences your work, and how you came to select these particular, seemingly disparate, writers?

Kuma Kitsune: I think what most influences my work is the Surrealistic concept of unleashing the unconscious.

The Book I Read Before I Was Ready: The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

When I was fifteen years old, my mother’s book club read The Red Tent by Anita Diamant. Whether she knew it or not, I was reading along with her.

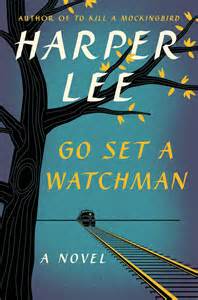

In Defense of ‘A Watchman’

Now that the hoi polloi have had a chance to read Harper Lee’s “new” book, I don’t feel uncomfortable writing about it before most people have had a chance to make up their own minds. (Spoiler alert: those of you still on the waiting list at your local public library, I’m going to talk about the way Lee supposedly shreds the moral fiber of everyone’s favorite dad, a.k.a. Atticus Finch, like a log of string cheese. You probably already know about this though, unless you’ve just awoken from a coma. In which case: Hi. Welcome back. )

Now that the hoi polloi have had a chance to read Harper Lee’s “new” book, I don’t feel uncomfortable writing about it before most people have had a chance to make up their own minds. (Spoiler alert: those of you still on the waiting list at your local public library, I’m going to talk about the way Lee supposedly shreds the moral fiber of everyone’s favorite dad, a.k.a. Atticus Finch, like a log of string cheese. You probably already know about this though, unless you’ve just awoken from a coma. In which case: Hi. Welcome back. )

The Panic of Writing

I’m halfway through a three-week writing retreat at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia, and what has occurred to me over and over is how little time I build writing into my daily life, how haphazard it is, an afterthought, something I too easily cast aside.

Bad Kids at the Milk Tea Shop: Leisure Time, Reading and Writing in Chengdu and Neijiang, China

Luis Humberto Valadez was born and raised in Chicago Heights, Illinois. He received his MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poets at Naropa. His publications include the poetry collection what i’m on from the University of Arizona Press (2009) and the book/music project Valid Lush from Plumberries Press. After completing a term of service with the Peace Corps in Neijiang, Sichuan, China, he was hired by Peace Corps China as a TEFL Manager and is currently based in Chengdu. More of his work can be found at here. Valadez takes his job supporting Peace Corps teachers seriously, and also tries to fit in a literary life.

Singapore’s Literary Culture and the Power of a National Library

Image credit: Shravan Krishnan.

In a recent interview with SG Magazine, Malaysian writer and resident of Singapore, Tash Aw, criticized Singapore’s lack of literary culture. Calling out the country’s educational system, Aw says, “the whole thing about writing requires you to question stuff in general. Not necessarily political things, but from a personal point of view. It needs you to question stuff that’s going on inside yourself. Very basic things, like family. That’s not something the Singaporean educational system encourages.” Aw goes on to point out the Singaporean peoples’ general disregard for literature and self-history, their emphasis on work and social standing, as well as other cultural ideas.

In defense of his country, though, Aw offers this: “I think Singapore is very creative, with great film-makers and visual artists. Literature is the one thing that’s lagging behind. The Great Singapore Novel isn’t going to happen for a long time, because to have any novel, let alone a great one, you need to be able to draw upon reserves of experience. If you’re going to rely on that post-’65 narrative, then Singapore is a young country. Somewhere like Britain has had hundreds of years.”

The Purpose of Subversive Writing, Or, The Pastor’s Wife Has Tattoos

Subversion has been on my mind for at least six months now. I like the way the word sounds when I say it out loud. It moves toward the front of my mouth, over my tongue and lips, rolls back toward my throat, and finally lands on the tip of my tongue at the end of the last syllable.

As the word “subversion” rolls around the mouth, it’s also a word, in action, that deconstructs and challenges. It’s a hard-working word, frightening to those who hold power. The word comes from the Latin subertere, meaning “to overthrow.” I love the definition of the word: “An attempt to transform established social order and its structures of power, authority, and hierarchy.”

Literary Treasure Hunting in Cape Town

Between 2006 and 2012, I lived in and studied in Cape Town, South Africa. During my time there, I discovered works I never would have found in the States (where I’m from). I could have wept with joy when I occasionally, unexpectedly, stumbled upon great books in junk shops with low-low prices. It was like unearthing a treasure. I spent uncountable hours reading in the African sun—on a quiet corner of campus, on a beach off the Atlantic Ocean, under any tree I could find.

Catching #FerranteFever

If Italian author Elena Ferrante knows about #FerranteFever, the social media hashtag used by fans to describe their obsession with her books, I’d be willing to bet the phenomenon makes her uncomfortable. Possibly, she’s rolled her eyes about it. That’s because, in this age of selfies and shameless self-promotion, Ferrante is something of an iconoclast, eschewing all public appearances and social media, granting few interviews, and fiercely guarding her true identity (Elena Ferrante is a pen name).

If Italian author Elena Ferrante knows about #FerranteFever, the social media hashtag used by fans to describe their obsession with her books, I’d be willing to bet the phenomenon makes her uncomfortable. Possibly, she’s rolled her eyes about it. That’s because, in this age of selfies and shameless self-promotion, Ferrante is something of an iconoclast, eschewing all public appearances and social media, granting few interviews, and fiercely guarding her true identity (Elena Ferrante is a pen name).

In a rare interview with the author in the spring 2015 issue of the Paris Review, Ferrante declares herself “still very much interested in testifying against the self-promotion obsessively imposed by the media. This demand for self-promotion diminishes the actual work of art, whatever that art may be, and it has become universal.” She then goes on to explain the creative space that opened up for her when she realized that her anonymity would be protected by her publishers. “[It] made me see something new about writing,” she says. “I felt as though I had released the words from myself.”

Getting Lost

I’ve been getting lost lately. I’m forty now; getting mixed up and turned around isn’t a problem I recall having as a twenty-something. It began one day in my late thirties when I went for a walk by myself in the subdivision where my brother lives with his family. Only the day before, I’d gone for a run with my seven-year-old niece, who rode her bike. She suggested we head to the back side of the subdivision, where I’d never been before. She was confident we wouldn’t get lost. I followed her, and as she promised, we made it safely back without incident. I thought I’d paid attention to the path she took.

John Ashbery and the Eastern Bloc: The Absurd is Our Guide

John Ashbery, My Guide

John Ashbery, My Guide

The past three decades have been an exciting time for poets from formerly Soviet nations. Many contemporary poets from this region came of age (and established their voices) while poetry was inextricably linked to rebellion against communist regimes. You were a protest poet—or you weren’t a poet. But after the dissolution of many corrupt governments in the 1980s, poets were able to inhabit or create different identities—even apolitical ones.

I find myself hungry for these voices, and want to hear their stories. I’ll be the first to admit I often lack the context for the works—and I’m reading English translations to boot. As an American reader, I lean on more familiar poets to be my guides. Slovenian poet Tomaž Šalamun has often cited his affinity for (and influence by) American poet John Ashbery. And so, Ashbery has been my escort through Šalamun and other poets from this region.

My Murderous Heart

Last year, I wrote a confessional essay in honor of the 2015 Lenten season about a time I nearly killed my ex-husband. It was recently published in The Cresset. Several of my friends read it, discovering that, at one time, I’d had a murderous heart. You never know, of course, if anyone will read your work or if it will go unnoticed. I had hoped for oblivion for this one mainly because it was difficult to know how friends and colleagues would react. I do a tolerable job of helping others think I’m homespun, normal—I think we all do this. It helps us gloss over the messiness of life and makes day-to-day interactions easier.

Assumptions in the Desert

“There was a wall. It did not look important. It was built of uncut rocks roughly mortared. An adult could look right over it, and even a child could climb it.” -The Dispossessed, Ursula K. LeGuin

We make assumptions. For example, as a writer, I make assumptions about my audience, about you. One of those assumptions is that you read, most of you widely, and many of you deeply. Since this blog is attached to a literary journal, it is very possible that some of you write. At the same time, I could be completely wrong. That is the nature of assumption after all.

Last week, my wife and I were driving through a small town in the Utah desert. The evening was approaching and I was hungry. The next town was probably an hour off. The problem was that we only passed two restaurants on the highway, China Star and Pizzaria. Take a moment to look at the pictures and you might make some assumptions of your own.

Remembering “Before I Forget” by Andre Brink

The first time I went to Cape Town, South Africa, I was about to turn twenty. A junior in college, I had little experience with life, love or literature and I was hungry for more. In the Cape Town library, I discovered Before I Forget, Andre Brink’s shameless fictional recollection of lovers possessed by the book’s narrator—who happens to be an aging South African author.

The first time I went to Cape Town, South Africa, I was about to turn twenty. A junior in college, I had little experience with life, love or literature and I was hungry for more. In the Cape Town library, I discovered Before I Forget, Andre Brink’s shameless fictional recollection of lovers possessed by the book’s narrator—who happens to be an aging South African author.

I was captivated.

When I decided to reread it nine years later, all I could remember was that it was indulgent. In the opening pages, eighty-year-old Chris Minaar sets up the premise: He’ll recount every woman with whom he’s slept over the course of his long, debauched life as a white South African novelist.

We Are Made of Words

When I think of words, I imagine a terrain and see myself as an amateur geologist of sorts. The words are stones, shaped by the passage of time, by the elements. I pick one up and examine it to get a feel for its weight, shape, edges, size and proportion to others. I hold it up to the light to get a sense of its tint and hue, trying to decide what new dimension it will add to my collection. I recognize it as a weapon, a fragment of a puzzle, as evidence. As building material.

I celebrated my fortieth birthday a few weeks ago, and received a gift, the very best gift: Words. They came in the form of short, personal notes from several of my students (I teach at a small college in northern Indiana). They wished me a happy day and encouraged me by explaining their experiences in my classrooms. I don’t know who organized such a thing. I didn’t tell anyone beforehand that it was my birthday (though, on the day, it splashed across Facebook). Someone anonymously delivered the notes to my office. It was hush-hush, a surprise. By the time I finished reading, I was in tears.

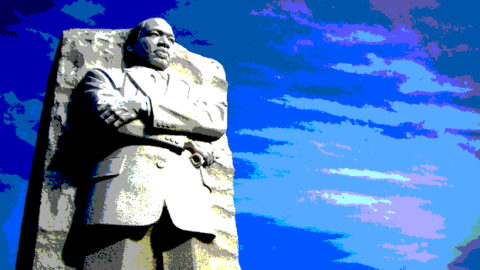

Pre-K & MLK

What Doesn’t Kill You Makes Someone Else Stronger

NaNo FAIL; Or, How Cello Lessons Had No Impact on My Ability to Write a Novel

Last November, I posted about how taking cello lessons inspired me to participate for the first time in NaNoWriMo, or National Novel Writing Month. Since then, a lot of people have asked me how the experiment panned out. I’ve been waiting—partly from shame, and partly for the enhanced perspective that is the reward of time—to admit that I failed to produce a complete novel in a single month.

The last few days of November were excruciating. I woke up on November 30th with my inner voice screaming, “You failed! You are a failure! A fail-y, fail-y FAILURE!” Like I’ve said before, my inner voice is a jerk.