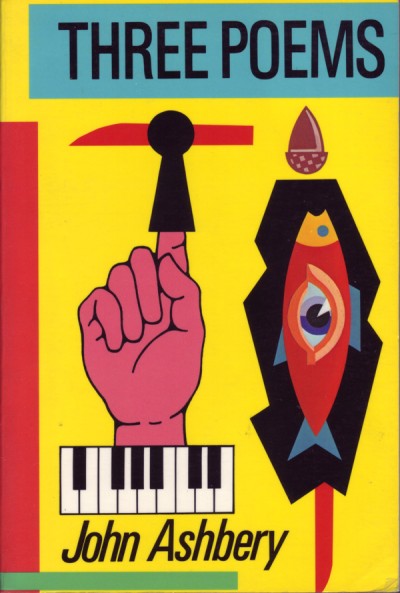

John Ashbery, My Guide

John Ashbery, My Guide

The past three decades have been an exciting time for poets from formerly Soviet nations. Many contemporary poets from this region came of age (and established their voices) while poetry was inextricably linked to rebellion against communist regimes. You were a protest poet—or you weren’t a poet. But after the dissolution of many corrupt governments in the 1980s, poets were able to inhabit or create different identities—even apolitical ones.

I find myself hungry for these voices, and want to hear their stories. I’ll be the first to admit I often lack the context for the works—and I’m reading English translations to boot. As an American reader, I lean on more familiar poets to be my guides. Slovenian poet Tomaž Šalamun has often cited his affinity for (and influence by) American poet John Ashbery. And so, Ashbery has been my escort through Šalamun and other poets from this region.