Nihil Est Machina: Finding Literary Beauty in a Godless Universe

In the volatile world of the internet, I still occasionally come across the notion that not believing in a god is to not believe in anything. Non-believers are still all too frequently seen as cold and cynical, undervaluing the world if they value it at all.

The Book I Read Before I Was Ready: The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

When I was fifteen years old, my mother’s book club read The Red Tent by Anita Diamant. Whether she knew it or not, I was reading along with her.

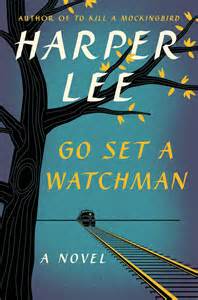

In Defense of ‘A Watchman’

Now that the hoi polloi have had a chance to read Harper Lee’s “new” book, I don’t feel uncomfortable writing about it before most people have had a chance to make up their own minds. (Spoiler alert: those of you still on the waiting list at your local public library, I’m going to talk about the way Lee supposedly shreds the moral fiber of everyone’s favorite dad, a.k.a. Atticus Finch, like a log of string cheese. You probably already know about this though, unless you’ve just awoken from a coma. In which case: Hi. Welcome back. )

Now that the hoi polloi have had a chance to read Harper Lee’s “new” book, I don’t feel uncomfortable writing about it before most people have had a chance to make up their own minds. (Spoiler alert: those of you still on the waiting list at your local public library, I’m going to talk about the way Lee supposedly shreds the moral fiber of everyone’s favorite dad, a.k.a. Atticus Finch, like a log of string cheese. You probably already know about this though, unless you’ve just awoken from a coma. In which case: Hi. Welcome back. )

Bad Kids at the Milk Tea Shop: Leisure Time, Reading and Writing in Chengdu and Neijiang, China

Luis Humberto Valadez was born and raised in Chicago Heights, Illinois. He received his MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poets at Naropa. His publications include the poetry collection what i’m on from the University of Arizona Press (2009) and the book/music project Valid Lush from Plumberries Press. After completing a term of service with the Peace Corps in Neijiang, Sichuan, China, he was hired by Peace Corps China as a TEFL Manager and is currently based in Chengdu. More of his work can be found at here. Valadez takes his job supporting Peace Corps teachers seriously, and also tries to fit in a literary life.

Singapore’s Literary Culture and the Power of a National Library

Image credit: Shravan Krishnan.

In a recent interview with SG Magazine, Malaysian writer and resident of Singapore, Tash Aw, criticized Singapore’s lack of literary culture. Calling out the country’s educational system, Aw says, “the whole thing about writing requires you to question stuff in general. Not necessarily political things, but from a personal point of view. It needs you to question stuff that’s going on inside yourself. Very basic things, like family. That’s not something the Singaporean educational system encourages.” Aw goes on to point out the Singaporean peoples’ general disregard for literature and self-history, their emphasis on work and social standing, as well as other cultural ideas.

In defense of his country, though, Aw offers this: “I think Singapore is very creative, with great film-makers and visual artists. Literature is the one thing that’s lagging behind. The Great Singapore Novel isn’t going to happen for a long time, because to have any novel, let alone a great one, you need to be able to draw upon reserves of experience. If you’re going to rely on that post-’65 narrative, then Singapore is a young country. Somewhere like Britain has had hundreds of years.”

Literary Treasure Hunting in Cape Town

Between 2006 and 2012, I lived in and studied in Cape Town, South Africa. During my time there, I discovered works I never would have found in the States (where I’m from). I could have wept with joy when I occasionally, unexpectedly, stumbled upon great books in junk shops with low-low prices. It was like unearthing a treasure. I spent uncountable hours reading in the African sun—on a quiet corner of campus, on a beach off the Atlantic Ocean, under any tree I could find.

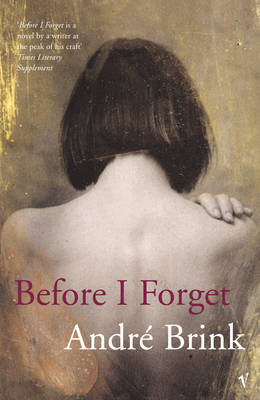

Remembering “Before I Forget” by Andre Brink

The first time I went to Cape Town, South Africa, I was about to turn twenty. A junior in college, I had little experience with life, love or literature and I was hungry for more. In the Cape Town library, I discovered Before I Forget, Andre Brink’s shameless fictional recollection of lovers possessed by the book’s narrator—who happens to be an aging South African author.

The first time I went to Cape Town, South Africa, I was about to turn twenty. A junior in college, I had little experience with life, love or literature and I was hungry for more. In the Cape Town library, I discovered Before I Forget, Andre Brink’s shameless fictional recollection of lovers possessed by the book’s narrator—who happens to be an aging South African author.

I was captivated.

When I decided to reread it nine years later, all I could remember was that it was indulgent. In the opening pages, eighty-year-old Chris Minaar sets up the premise: He’ll recount every woman with whom he’s slept over the course of his long, debauched life as a white South African novelist.

NaNo FAIL; Or, How Cello Lessons Had No Impact on My Ability to Write a Novel

Last November, I posted about how taking cello lessons inspired me to participate for the first time in NaNoWriMo, or National Novel Writing Month. Since then, a lot of people have asked me how the experiment panned out. I’ve been waiting—partly from shame, and partly for the enhanced perspective that is the reward of time—to admit that I failed to produce a complete novel in a single month.

The last few days of November were excruciating. I woke up on November 30th with my inner voice screaming, “You failed! You are a failure! A fail-y, fail-y FAILURE!” Like I’ve said before, my inner voice is a jerk.

Who Decides the Humanities’ Future?

I’ve just stumbled across yet another depressing article about the bleak future of the English Major. They usually go something like this: People are reading less, it’s terrible, woe to we who write! I read these types of articles because they are posted in literary magazines, by and for people concerned with the decline of reading and literature. But I believe articles of this ilk may be missing the point.

However well-intended and meticulously researched, the journalistic approach of this type of article lacks the essence of the discipline they are discussing. Literature and the arts are not about facts and figures, they are about what it means to be human, hence the label: the Humanities. Literature seeks to expose the truths of human existence, the shared experience, the feeling of being alive. So, in my first post for Newfound, I find myself looking for my place in all this cognitive shifting sand.