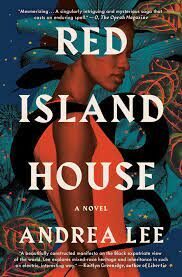

Red Island House: An Interview with Andrea Lee

Gary Percesepe

In the following interview with poet and philosopher Gary Percesepe, Andrea Lee reflects on the sources and influences of her new novel, Red Island House; the enduring beauty, poverty, and legacy of colonialism in Madagascar; the unique challenges of a Black American woman confronting cultural differences in a remote African nation; Jacques Derrida’s notion of survie as linked to notions of inheritance, memory, guilt, forgiveness, and the unforgivable; and whether Madagascar has a future. The New York Times ran an excerpt of Red Island House, which Newfound readers can find here. The daughter of a Black pastor who grew up in a prosperous Black neighborhood in Philadelphia, Lee is currently writing a memoir with the working title, Lincoln Went Down to the Nile.

GP: Andrea Lee, welcome to Newfound. Red Island House is so many things at once: an epic novel set in the remote African island of Madagascar; a look at neocolonial ravages in one of the poorest countries on earth; a deconstruction of the idea of “Paradise”; a narrative of a Black American heroine confronting her ancestral continent. What inspired you to write it?

AL: The novel grew out of my experience as a sojourner in Madagascar–that’s to say, someone who has visited the country every year since the late nineties. For a long time I resisted writing it because I felt my knowledge of the country was too shallow. As you know, I live in Italy, where the Indian Ocean is a popular tropical destination, and my family and I came to Madagascar purely as vacationers. Madagascar is one of the most beautiful places in the world, a huge Indian Ocean island with astounding biodiversity and a unique cultural mix, and it was easy to be captivated by the coral beaches, the lemurs, the baobabs, the intricate mixture of indigenous peoples. It was also impossible to ignore the fact that the country, a former French colony, is one of the world’s poorest, and carries the scars of centuries of foreign exploitation. Underneath my enjoyment I felt a queasy guilt at my own privilege.

As always, though, I was looking and listening, gathering up anecdotes from those coastal places where Malagasy and foreigners mingle. One night we ate in a pizzeria called Libertalia, with a pirate painted on the wall, and there I heard a local legend about a shipload of French and English pirates who found the coast so beautiful that they built a crude settlement of the same name: a brawling, “liberty”-minded colony that scandalized the local tribes and was finally eradicated in slaughter and flames.

That 200-year-old tale pushed me to write my novel. For a long time, I’d been intrigued by the trope of tropical paradise: first, that places so described often have a colonial past, and second, that modern foreigners who settle down on palmy beaches often find, not Arcadia, but existences full of misadventure. Behind the hotels and dive centers in Madagascar, I saw the ugly evidence of hyper development, sexual tourism, pillaging of resources.

So my Madagascar observations inspired stories, some of which appeared in The New Yorker. And then I joined them together into a larger narrative, a novel with a theme of neocolonialism. I wanted to explore what happens when humans try to exploit paradise: a parable of the Fall of Man. My working title was Paradise Twisted. To unify the novel, I created a single setting: a big villa, the Red House, built by foreigners on an edenic islet in Madagascar. I named the islet “Naratrany.” In Malagasy, the word means “wounded land.”

GP: I was fascinated by the physical description of the Red Island house itself, with floors that look like blood. You described it to me once as “a discount Tower of Babel.” How did these images of the house come to you?

AL: Traveling in the Indian Ocean, I saw the huge Italian villas of Malindi, and other grandiose European vacation houses, and I was struck by their vulgarity. On my first visit to Madagascar, we stayed in a decaying beach villa built in the 1950s, the last decade of French colonization. It was by far the grandest building in a community of fishermen and cane workers, and I immediately equated it with the big house on a plantation. That house had a gloomy, haunted atmosphere; I had horrible dreams there. The floors were painted a deep red common to a lot of old European houses in the region, but to my imagination this color irresistibly suggested bloodshed, an accumulation of old crimes. So, the Red House came into being, an emblem of human greed and colonial depredation. I intended the place to be–like Manderley, or Tara–an almost living presence.

GP: The main character in Red Island House is Shay, who is deeply conflicted on many levels. The “arc” of her character in this novel is fascinating. It is easy for you to relate to her?

AL: Shay is a unique literary character, a Black American woman confronting cultural differences in a remote African country. Her interior journey is the thread joining the vignettes that make up Red Island House. It’s easy for me to relate to her; through her I wanted to express an aspect of myself–my reaction to Madagascar, which ranged from a confused feeling of kinship with people who looked like me, to a deep shame at my own entitlement. I envisioned her as perceptive and adventurous, married to an Italian but deeply attached to her Black American heritage; so I made her an expatriate professor of black literature. Still, for all her learning, Shay is thrown off balance by Madagascar, and that conflict drives the narrative.

In her story, I wanted to play with another colonialist literary trope: the swashbuckling adventure yarn, where an explorer battles his way through a savage land. As a child I loved H. Rider Haggard and his genre, and always longed to see a heroine who was more like me. So I decided to subvert the old stereotype of a white man in a pith helmet, and create a Black heroine of the diaspora, who goes deep into the unknown continent of her ancestors. As the years pass, she gains humility and wisdom. The greatest challenge she faces is having to confront her own privilege as part of the developed world, her personal heart of darkness. And Shay does encounter “savages,” but in general their skin is white.

GP: The vivid descriptions of smells, tastes, sounds, and views made me feel as if I had spent a year in Madagascar. Beyond this, the book is a compendium of detail about the culture of the country. What research did you do for the book?

AL: As I said, I hesitated at first. In this period of public discourse about appropriation, the project seemed a bit presumptuous. So, I decided two things. The first was to focus on the in-between world of resident foreigners. The second was to offer respect to the country by researching history and cultural detail, thus avoiding the typical American tendency to see African countries as an undifferentiated mass.

Madagascar has one of the richest literary traditions of any African country–the first literary review in Africa was founded in the nineteenth century by Malagasy writers. I read poetry and prose from authors like Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo and Naivo (Patrick Naivoharisoa), as well as translations of the ancient national oral epic, Ibonia, and oral poetry like the Malagasy hainteny. I read foreign missionaries’ records, and the journals of Dutch slavers in the Indian Ocean. I read the eighteenth-century General History of the Pyrates by Captain Charles Johnson, which recounts the myth of Libertalia.

And I explored outsiders’ fantasies about Madagascar, such as seen in early letters of Paul Gauguin–did you know that he first planned to live there, instead of Tahiti? And then, there is Hitler’s horrific plan to exile Jews to Madagascar. In Noel Coward’s Private Lives, frivolous socialites dream of escaping to Madagascar, as does Natasha in Tolstoy’s War and Peace. William Burroughs’s surrealistic novella Ghost of Chance takes place in Madagascar. Throughout the novel, I include pieces of this information to honor the complexity of a country familiar to most people around the world only through the Dreamworks film franchise.

GP: You grew up as the daughter of a pastor of an historic Black Baptist church in Philadelphia. As a philosopher and pastor of a church myself, I sense a deep, though not obvious, spirituality in this novel, particularly at the end, which I found deeply moving. I want to ask you what part does the sense of the sacred play in it? And do you feel that there is a kind of redemption operative in this novel?

AL: To open the novel, I borrowed a quote from Naivo, one of the foremost young Malagasy writers: “Madagascar is a sacred country, though at the mercy of outside interests.” And certainly, to me at least, there is an intense spirituality diffused through the air of the place. This may connect to the fact that, besides Christianity and Islam, one of the official state religions is Animism, which lends a sense of soul life to the landscape. As someone who grew up in a religious family, I sensed this atmosphere immediately–and I also felt that the damages wrought by human-induced climate change and foreign exploitation were a spiritual violation.

The novel ends with a look at the future and the new life it brings. Although there is loss and destruction, there is also birth. And birth is always a sacred event, bringing with it, however briefly, a primal sense of hope. I wanted to suggest the idea as well that the profound violence of colonialism is always in some ways accompanied by the creation of a new culture–a mixed culture–that springs up inevitably in spite of the bitter facts of conquest, enslavement, destruction, racism, classism, plundering. As Shay is forced to recognize, no culture colonizes another without being subtly colonized itself. So Red Island House does not have a happy ending, but it offers the redemptive sense that humanity survives and evolves.

GP: As you know, I’ve written about the French philosopher Jacques Derrida. In our correspondence, you mentioned Derrida’s notion of survie, which in Derrida and Emmanuel Levinas is linked to notions of inheritance, memory, guilt, forgiveness, and the unforgivable. Shay, of course, is an academic who would be familiar with these broad themes in the Western tradition. I’d love to see literary critics and philosophers pick up on these themes in your work. Is there ever really a post in post-colonial? As Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” What Ibram X. Kendi calls “racialized capitalism” is ravishing the island, along with the rest of Africa. The continent of Africa today is almost 90% unvaccinated for COVID. Of course, this question, posed from within the Christian tradition, cannot even be asked apart from the notion of hope. Another way of asking this question is, what hope is there for Madagascar today?

AL: To me, Derrida’s survie in general suggests the capability to witness and endure–to accept–paradox. I mean the Tiresian gift for contemplating both sides of the coin at once: past and present, self and other, life and death, male and female, oppressor and victim—and, as you have said, forgiveness and the unforgivable. By the end of Red Island House, Shay is approaching a glimmer of this kind of visionary acceptance.

As for the future of Madagascar, I think that hope is a subjective thing when you are dealing with a largely marginalized country of 30 million people, most of whom struggle to survive on less than a dollar a day, an island nation already enduring the ravages of climate change, where thousands in the famine-ridden Southern regions are reduced to eating locusts. As you have suggested, neocolonialism is alive and well, in the form of sex tourism, environmental degradation, and Wild West-style plundering of resources by kleptocratic politicians allied with foreign states. Yet, at the same time, those Malagasy who are surviving have an almost magical resilience and creativity: the country has a high literacy rate and is one of the most digitally advanced of any African nation, while the capital, Antananarivo, is home to an exploding art and music scene. There is an incredible young population–the median age in Madagascar is twenty–that is very future-minded, striving against all odds for a place in the contemporary world.

GP: These are complex themes you address. Was it difficult initially to identify an audience for the book?

AL: I think that in the industry there was an eagerness to pigeonhole it as a very different kind of book: a more conventional novel about love, marriage, and travel, against a flat, exoticized tropical background. In fact, I was advised by an experienced friend that it was best not to mention the word “identity” or “colonialism” in my book discussions, as it might hamper marketing! I found this very frustrating–yet now it seems that the book has reached its proper audience: readers interested in exploring cultural collision and the legacy of history in one of the most beautiful and least-known countries on earth.

GP: Andrea, you are currently writing a memoir. What can you tell us about it?

AL: In a way, I’m addressing the subject of Arcadian fantasies all over again. My memoir is called Lincoln Went Down to the Nile. It describes my childhood in the sixties and seventies in a prosperous Black suburb outside Philadelphia: an aspirational place in which the neat lawns of Lincoln Avenue did indeed run down to the Nile Swim Club–the first Black swim club of America. The doctors, ministers, teachers, and businessmen of the neighborhood were deeply involved in the civil rights movement, but also devoted to achieving the American suburban dream for their families. The result was a feeling of mingled comfort and uneasiness that influenced their children: an extraordinarily creative generation of Black writers, filmmakers, artists, and intellectuals, who grew up in that idyllic green space. I think the subject is particularly timely as attention has recently been drawn to the strong Black communities of the past, lost to deliberate destruction, or dissipated through increased possibilities offered by integration.

After writing about a place as far away from my American roots as Madagascar, it’s very moving for me to return to home territory. The more that I write about countries where I live as a foreigner, the more fascinating I find the small landscapes of my growing up. Even in the familiar there is always some deep mystery to explore.