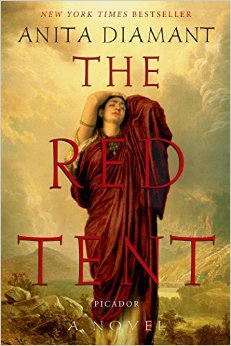

When I was fifteen years old, my mother’s book club read The Red Tent by Anita Diamant. Whether she knew it or not, I was reading along with her.

The Red Tent is a fictional (yet thoroughly researched) first-person account of the life of Dinah, the only daughter of Biblical patriarch Jacob (who is more famous for having twelve sons). With Dinah’s help, women’s histories are traced matrilineally; daughters, sisters and mothers are remembered and honored. Through Dinah’s eyes we see women come of age, begin menstruating, fall in love, make love, bear children, bear losses, age and die. It is by turns tender and irreverent. Oh yes, there are love scenes.

I was totally unprepared for this book.

Just to give some context to my reading life up until that point: I was scandalized when I read about Rachel, Jacob’s most beautiful wife, using traditional medicine to help her conceive—specifically a mandrake root, which “looked so much like an aroused husband.” I was also confused. Mandrakes are used for magical purposes in the world of Harry Potter! I had no idea what “an aroused husband” looked like, and I couldn’t imagine running into one on the Hogwarts campus.

I was a sophomore in Catholic high school and I felt this book’s impacts immediately. Studying the Old Testament in religion class, the injustice of learning of only Biblical patriarchs was made starkly apparent to me. I’d played the lead in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat in seventh grade, so I felt a connection to Jacob’s favorite son. But Dinah’s silence, I realized, wasn’t a temporary injustice of the “Close Every Door” variety. Jacob’s only daughter was never saved or resurrected during my U.S. Catholic education. I had to find her on my own.

In class, I shuddered when a fellow student had to read out loud the list of Jacob’s children and mispronounced Dinah’s name. Dinah introduces herself in the opening passage, “the first vowel high and clear, as when a mother calls to her child at dusk; the second sound soft, for whispering secrets on pillows. Dee-nah.” But everyone in my classroom said it in the “Mama’s in the kitchen with Dinah” way, and I could only grit my teeth.

This book’s impacts on me deepened with time.

I never stopped wondering about the women of the Bible, and was unsatisfied with the limited ways their actions, intentions and words were recorded. This book gave me a lifelong thirst for women’s voices in my fiction. (And history. And spirituality.)

The Red Tent itself was where women in Dinah’s family went during menstruation. They were secluded from their husbands or sons, but rather than feeling shame in this, they comforted each other and celebrated the power of their bodies. This book made me very comfortable with menstruation. I don’t think I could have been such a supporter of The Vagina Monologues in college if I hadn’t read this as a teenager.

But I am skipping ahead: When I went away to college, I covered my extra-long twin dorm bed in fire-red sheets. When a new friend visited my room, she saw a sheet hanging off my top bunk bed and said my dorm was the Red Tent. I got the reference and started gushing about Diamant’s book, which she had also read. I was amazed by the ways she told me that book had inspired her.

I learned that she’d already picked out her first daughter’s name: Dinah. When I visited her parents’ house, I saw a painting she’d made of how she imagined the character Dinah’s face.

That year we forged a lifelong friendship with ancient tales of mothers, sisters and daughters as its bedrock. This friend is a nurse and midwife, now—fulfilling another dream inspired by The Red Tent.

Laura Eppinger graduated from Marquette University with a degree in Journalism. Her laptop screen got cracked during a year in Cape Town, South Africa, but it never stopped her from writing. Her publications list lives here.

Laura Eppinger graduated from Marquette University with a degree in Journalism. Her laptop screen got cracked during a year in Cape Town, South Africa, but it never stopped her from writing. Her publications list lives here.

I first encountered The Red Tent in college and it had a profound impact on me as well. I was studying Judaism in preparation for my conversion and my sponsoring rabbi recommended I read the book. I’m really glad I did, since it greatly expands the story of Dinah, who is mentioned only in passing in the Bible and is presented as a victim. I really appreciated Diamant’s efforts to develop Dinah’s character and to give her a voice and identity.