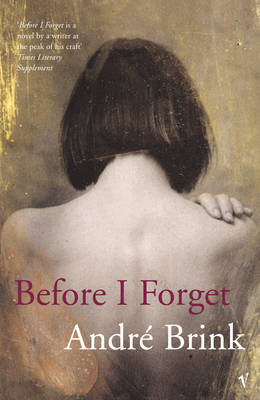

The first time I went to Cape Town, South Africa, I was about to turn twenty. A junior in college, I had little experience with life, love or literature and I was hungry for more. In the Cape Town library, I discovered Before I Forget, Andre Brink’s shameless fictional recollection of lovers possessed by the book’s narrator—who happens to be an aging South African author.

The first time I went to Cape Town, South Africa, I was about to turn twenty. A junior in college, I had little experience with life, love or literature and I was hungry for more. In the Cape Town library, I discovered Before I Forget, Andre Brink’s shameless fictional recollection of lovers possessed by the book’s narrator—who happens to be an aging South African author.

I was captivated.

When I decided to reread it nine years later, all I could remember was that it was indulgent. In the opening pages, eighty-year-old Chris Minaar sets up the premise: He’ll recount every woman with whom he’s slept over the course of his long, debauched life as a white South African novelist.

Things get interesting when we meet a lover named Daphne. It’s the 1970s; apartheid is at its height in South Africa. Minaar is twenty-something and Daphne is a willowy, blonde dancer. During a private dance, she reveals that she always wears a tight rope belt around her midriff. She is bruised, in constant pain, and abstains from sex. The reason she gives for torturing herself: “It’s this country. Don’t you see?”

A little background: This encounter takes place after the Soweto uprising of 1976, in which tens of thousands of Black African student protesters demonstrated against the designation of Afrikaans as the official language of national education. These peaceful protests were met with violent government retaliation. Many Afrikaans-speaking whites felt helpless and frustrated by the government’s injustice.

As I reread the book, I wondered about Daphne, and found myself wishing Brink had given her more of a voice. Daphne’s belt reminded me of Simone Weil’s hunger strike, and I was intrigued by the way she adopted her country’s agonies into her own body. Given more than one line of dialogue, would Daphne have expressed something similar to Weil? At twenty, I was the consummate student. I sought more words to consume, more information. I wanted authors to speak to me and I wanted to hang on every word.

Nine years of studying and reading and critiquing later, I am comfortable taking a book to task. This time around, it was Minaar’s character that stood out to me as most lacking.

Minaar likens himself to Scheherazade, claiming he retells the stories of his loves to amuse others and make sense of his life. This promises the reader exaggeration and magic, which Minaar delivers.

Nevertheless, Minaar differs from Scheherazade in a crucial way: Scheherazade is fighting for her life, against terrible odds. Minaar, on the other hand, is the portrait of privilege: white, straight, male, professionally successful. He’s more like King Shahryar, who beds and kills a new wife every night. Upon this reading, I felt that the novel fails because readers cannot draw convincing parallels between Minaar and Scheherezade.

Most of Minaar’s lovers have been white South Africans or Europeans, with a few exceptions. When we catch up to the modern day, Minaar is nostalgic over a Black South African woman he employed as a “Girl Friday.”

The nudge-nudge language suggests readers should be charmed by such a naughty tryst. But on my recent read, my antennae raised: this woman is much younger, from a historically disadvantaged ethnic group and social class, and Minaar’s employee. Can a relationship with such an unequal power dynamic have started with consent at all? We cannot know—we’re never told how it began, only that it ends, “ Like so many others. Married…what a waste.”

In fact, every woman of color with whom Minaar sleeps is his employee. While a pretty accurate portrayal of racial separateness in the New South Africa, the issue is never taken head-on by the narrator, nor discussed by any other character. The narrator’s blindness to these inequalities is his biggest shortcoming; the book’s is its reticence to comment on such matters.

I am also critical now of how convenient so many of the fantastical parts are. Minaar’s lovers are impossibly good-looking and insatiable; of course they could only be satisfied by a weedy novelist. Taken with an ironic avoidance of the realities of race and class in the New South Africa and some murky issues with consent, there were times I could not believe I used to love this novel.

Rereading the book was like holding up a mirror and seeing a past self. The past reader loved any words that were strung together, and wanted others to tell her how the world worked. Reading again, I wanted to demand that she demand more of what she read.

Laura Eppinger graduated from Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA in 2008 with a degree in Journalism, and she’s been writing creatively ever since. Her laptop screen got cracked during a year in Cape Town, South Africa, but it never stopped her from writing. Her publications list lives here.

0 comments on “Remembering “Before I Forget” by Andre Brink”