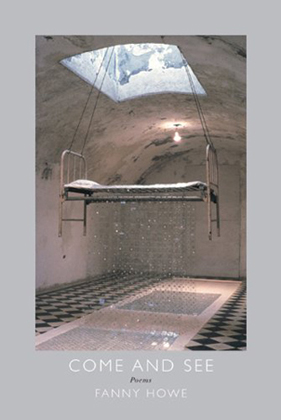

‘Come and See’

Caitlin McCrory

Fanny Howe, “Come and See”

Graywolf Press

2011, 94 pages, paperback, $15

Fanny Howe, the author of more than twenty books of prose and poetry and the winner of such awards as the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize and NEA grants, said of her work in a 2004 interview with the Kenyon Review: “If someone is alone reading my poems, I hope it would be like reading someone’s notebook. A record. Of a place, beauty, difficulty. A familiar daily struggle.” Fanny Howe’s latest collection of poems, “Come and See,” is just that, a place crafted out of one’s struggle to record and to reveal an often alluring, but ugly, history.

Fanny Howe, the author of more than twenty books of prose and poetry and the winner of such awards as the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize and NEA grants, said of her work in a 2004 interview with the Kenyon Review: “If someone is alone reading my poems, I hope it would be like reading someone’s notebook. A record. Of a place, beauty, difficulty. A familiar daily struggle.” Fanny Howe’s latest collection of poems, “Come and See,” is just that, a place crafted out of one’s struggle to record and to reveal an often alluring, but ugly, history.

The role that history takes, both through physical location and through metaphor in Howe’s work, seems to have some influence from a writer whom Howe admired, Ilona Karmel. Karmel was a Polish-Jewish prisoner of Nazi work camps who attempted to record and translate, in extraneous detail, her history and the history of other prisoners in such an awful place. Karmel’s experiences are contained in her work “An Estate of Memory.” Howe’s title poem, “Come and See,” the last poem in the collection, describes Karmel’s work as one that pursues the truth “through a relentless and unfavorable account of human behavior.” Where Karmel offered a decidedly wretched and heartbreaking firsthand account of the Nazis, Howe’s writing frames both the allure and disgust of the twentieth century through what appears as a wide-angle lens, capturing the horizon and placing the clouds just out of view, thus leaving her reader with the idea that there is some significant detail that can’t quite be seen.

Howe’s first poem, “This Eye,” sets the precedent for her collection, revealing her work as a documentary of the twentieth century. The reader witnesses the entrance into the Great War, WWII, and such crises as the fall of the Czars and the nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl. “This Eye” opens the poetry collection, as Howe’s speaker describes a scene of a young boy and his grandmother:

A boy reads about war

in bed with his grandmother.

She keeps getting up to look out

What she sees horrifies her.

That’s why she pulls the curtains

to protect the love she can’t see.

This grandmother, whom Howe described in a 2011 interview as “someone she almost recognizes as herself,” serves as an eye, or even a god, who looks out onto the world to document what she sees for Howe’s reader. However, there is a catch here with this eye because, as the eye of this speaker transforms through “Come and See,” she does not always give a clear view of what it is she witnesses. While the titles of Howe’s poems begin to offer detail about physical place (“The Grotto,” “Following Wang Bing,” and “The Rachmaninoff Hotel”), the structures of the poems themselves rely on abstract descriptions of “a stairway in a house or a velveteen bed spread” that seem to purposely lead a reader to generalize what it is he or she sees. As such, a reader may begin to feel frustrated at a point, as I did, having to question what, exactly, one is supposed to be a witness to: is it a place, a person, or even another record of the story being told? Then in the poem “Now I Have Seen Everything,” Howe’s speaker addresses the idea of ahistoricism, stating

He bent over me with the sadness of a specter.

We stayed like that with a floor length window open onto

the hangar

in an a-historical space. You can only confess once.

After that, there is very little to say about anything, especially

a lost chance.

This address from Howe’s speaker appears to imply that while in a place of ahistoricism, the chance to form a clear view and an honest record of history is minimal, at best. The speaker’s address of ahistoricism is linked, I presume, to the fact that many of us will always only almost recognize these people and these places that Howe describes, from Bieberkopf, Rasputin, Ratzinger to Chernobyl and Baghdad, because they’re aligned with a world outside our individual lives and outside our individual histories.

Even with Howe’s distinction of physical places in the titles of her poems and with reference to films like “The Ascent,” how we find ourselves engrained in, or a part of, a history we recognize outside of our own lives is not defined. Our definition of place within our histories becomes metaphorical then, as Howe’s work seems to hint, because, for the most part, we are now living lives where our own images are constantly reflected back to us, á la Jacques Lacan’s “mirror” or, similarly, Charles Horton Cooley’s “looking-glass self.” Because of this singular reflection, we see only what we wish to, we age as we wish to, we lie to ourselves as we wish to, and, most importantly, we ignore history as we wish to. The ability to almost recognize a world outside ourselves (and the world that the speaker in “This Eye” shows to the reader) becomes key to understanding the function of “Come and See” as well as Howe’s idea of a poem as a record.

Even in this recognition of mis-recognition, I wonder if the sort of ignorance I have described exists as a defense mechanism for survival, as the memory of historical events and figures may often appear ahistorical to our individual lives. To use Howe’s own words in “After Watching Klimov’s ‘Agoniya,’” “some moments in history last too long.” In some moments, we cannot remember these events as they were lived because to do so would mean our own metaphorical deaths. While this is not to excuse sheer narcissistic ignorance and disconnection—part of a larger theme that “Come and See” addresses—I was initially frustrated when I began to sort through the function of both place and ahistoricism in “Come and See.”

Even if I can follow Howe’s speaker and recognize the “tyrant” she describes to be Hitler, and even if I am able to see Hitler in photos and the terror he enacted, subjectively I still do not know the position from which Howe’s speaker bears witness; and that unknown brings me to tears because I’m forced to acknowledge that I’m a part of a history I can’t recognize. All I can recall is the terror and the pain of what I think has been lived since that moment, which is exactly the location Howe wants her reader to come and see.

Howe’s interest in recounting both the disgusting and the alluring history of the twentieth century that each of us are witness to and descended from best connects her work with Karmel’s and shares links with some of her contemporaries, including Carolyn Forché’s “The Angel of History” and Claudia Rankine’s “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely.” Each work is as heartbreaking as it is frustrating because the speakers attempt to move through a space where, as Howe writes

…love aches its way through the interstices.

Sticks like a dent in an inchworm’s back.

You can’t take it out because it is the thing in itself.

Love is the green in green. Does this explain its pain?

It’s precisely this love that aches with such pain that helps me finally recognize the place I was supposed to come and see. I see a history that I cannot escape, a history that wants to live, a history that does not call to the word “sacred” as a means of retelling the places of massacres, a history that reaches out from necessity because “only that which exists can be spoken of.” As the specificity of places are recalled in “Come and See,” from Gaza to Templars Square along with the archetypal family figures, not to mention Nietzsche and Kerouac, a reader’s inability to clearly recognize an event or a person transforms into a desire—a necessity—to have a history where pain and grief and sorrow and love are spoken of and continue to exist. Without such a story, what sort of life is it that we are living?

I think of all that Howe has written, knowing that in a matter of weeks I will have to co-lead a writing workshop for returning veterans at the university where I teach. Then, I will have to face not the Baghdad and the decisions that the Bushes made, as Howe describes in “Come and See,” but the faces of my students and the history that is written into them and the place where “the skin is no longer the veil,” where my disconnection will no longer be my role. I take from “Come and See” “the love that aches its way through the interstices” and the pain of knowing that

It was a terrible century:

consisting of blasted

oil refineries and stuck ducks,

fish with their lips sealed by plastic

and tar in the hair of cooks.

Filth had penetrated the vents.Institutions moan from the bowels.

Balls of cotton

from the hospital dumpster, redden.

Yawning in obsolescence

the computer wonderswho punched in such poor grammar.

First padded virgins

graduate to this suffering drama

all by her-selves.

Who were once cells.History is more than just another surmising

grandmother at a window…

Even in our own frustration and uncertainty as to what role we believe history takes in our lives, or even what that history looks like, we’ll have to face opening the curtains at that window to remember what it is to let in “the light that wants to live” and to see what we’ve been missing just beyond the horizon.

Caitlin McCrory, Poetry Editor.

0 comments on “Review: McCrory”