Upending the Myth:

On torrin a. greathouse’s

‘Wound from the Mouth of a Wound’

A review by Brandon Thurman

torrin a. greathouse, “Wound from the Mouth of a Wound”

Milkweed Editions, 2020

66 pages, softcover, $16

In the original myth, it was Perseus who beheaded Medusa, a violence preserved in story and later in stone. In Cellini’s grotesque 16th century sculpture, a curly-haired Perseus appears to be stepping blithely onto and over Medusa’s body while holding her head aloft in casual victory. From far away, it’s difficult to tell whose scalp is covered in snakes—his or hers.

In the original myth, it was Perseus who beheaded Medusa, a violence preserved in story and later in stone. In Cellini’s grotesque 16th century sculpture, a curly-haired Perseus appears to be stepping blithely onto and over Medusa’s body while holding her head aloft in casual victory. From far away, it’s difficult to tell whose scalp is covered in snakes—his or hers.

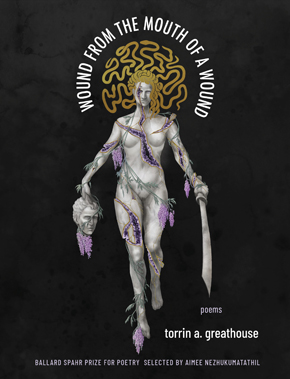

The cover of torrin a. greathouse’s collection of poetry, “Wound from the Mouth of a Wound,” and its opening poem, “Medusa with the Head of Perseus,” inverts this myth, using Luciano Garbati’s 2008 sculpture as a sort of mirror held up to that violence. In Garbati’s sculpture—which currently stands defiantly in a New York City park staring down the courthouse where Harvey Weinstein stood trial—it is Medusa who holds a sword in one hand and Perseus’s head in the other. She glares stonily ahead, as if demanding the viewer to answer a central question: Which of the two of them is the monster?

▱

Snake-headed Medusa is a character straight out of a Freudian nightmare, a character seemingly unworthy of sympathy. But greathouse immediately corrects this in the first stanza of her book: “I do not want to speak about the beginning / of this story,” they start. “But you already know the myth: rape / that made the body punishment for itself.” That myth is more than appropriate in the age of #MeToo, so it’s difficult to believe it is thousands of years old: A god rapes a woman in the temple of another god who, blaming the woman, turns her into a monster. As horrifying as it is, readers hardly even need to be told the backstory. As greathouse says, even if readers haven’t heard the story before, “you already know the myth.”

In beginning their collection with this myth, greathouse asks that the coming poems be read in its context. “My family is the myth of an animal devouring / itself,” greathouse writes.

… My mother

disowns me & suddenly I am a folktale.

Am I the serpent-headed girl? Or her endless

reflection? Or the winged mare burst

forth from her blood? Child of slaughter.

Wound from the mouth of a wound.

Like Pegasus springing from Medusa’s wound, greathouse’s book propels forward from there in five parts through her questions of lineage, violence, body, transphobia, and ableism.

▱

A childhood home, choked “slowly, gently” by wisteria. This is the metaphor greathouse chooses for their own body, going on to liken a doctor’s litany of prescriptions to how her mother would whitewash their porch, “how she knew the structure was beyond repair & still insisted on a graceful collapsing.” Occupied by phlebotomists, doctors, nurses, and therapists, the poems in the first section find the speaker constantly under the eye of the medical professional, forced to fight for her own dignity ad nauseum. And so, when they say “disabled,” she immediately strikes it out, again and again. greathouse pushes back against how her society labels bodies like hers as “broken,” “outliers,” or “abnormalities.” Society looks at their body and asks, “If a clock is broken do you repair it or / ask the world to conform to its sense of time?” Society asks, “If we discover a new and hungry / sickness is it our duty to cure it or to let it be?” As greathouse points out, these questions are formulated so as to be “rhetorical,” their answers obvious, unspoken. Throughout the collection, however, greathouse allows the speaker’s body to trouble those lazy formulations. Pulling herself out from under the critical gaze of the medical professional, greathouse chooses instead to hallow her own body. In “Hydrocele,” a nurse points out to them how “the mouth of a muscle that could have become a doorway / to the womb—failed to close.” greathouse responds with a moment of awe, with silent praise for “this body’s reluctance to be named son.”

▱

At the end of the first section, the speaker finds herself transitioning not at first into a “daughter,” as she says, but into a “flood.” From long pent-up tears spill a jumble of “fish hooks,” “my mother’s curls,” “prom tickets,” and “handfuls of baby teeth.” The reader is washed by this flood into section two, which more deeply explores the characters of the speaker’s father and mother, as the speaker dares now to look at her body through their eyes. In “Ode to the First Time I Wore a Dress & My Mother Did Not Flinch,” the speaker is disheartened that her mother

… will see this

velvet slip as nothing more than tender

skin to be shed bloody from a boy

to make from him a man.

This is a speaker who knows herself but who also knows acutely how a careless observer might perceive her.

One of the most striking aspects of greathouse’s work in this collection is its formal ingenuity. The titles themselves are almost exhilarating in their originality; the reader encounters first “Phlebotomy, as Told by the Body” and later “Phlebotomy, as Told by the Skin.” One poem splits itself in two as the speaker tries to decide which public bathroom to use. greathouse weaves throughout the manuscript a series of what they call “essay fragments,” complete with footnotes and annotations. Most notably, at the start of section two, greathouse introduces her brilliant invented form, the burning haibun, taking a prose poem and, through erasure, burning it down until it is a haiku. One senses that greathouse is enacting this same burning erasure throughout all of section two, blacking out the many judgments of the speaker’s parents, reducing their violence to its simplest form—something that can be counted out in syllables, even if its meaning remains elusive.

At the same time, the speaker finds herself being erased and is troubled by what she finds in the dark gaps left behind. Having erased her father’s fists and the alcohol on his breath, her first haiku still finds “father hidden in / erasure of me.” As the speaker reflects on their eating disorder in “All I Ever Wanted to Be Was Nothing at All,” she remembers how her “mother used to say if I just turned / sideways / I would disappear.” That disappearing takes on a parallel form to one of greathouse’s haibun: As her parents try to erase her, to black her out in their shadows, she stops them in their tracks, refusing to “say the word / scorching both our tongues,” but still remembering “how my family taught me / my body as another name for pyre.” Some things can’t be erased. Memory—and grief—burn on, never seeming to consume their source.

▱

In section three, the poems turn to childhood and enter into a more narrative mode, softening into a vulnerability that feels apt when considering that stage of life. This central section is, in many ways, the heart of the collection, laid open. It begins with that universal nightmare of one finding themself at high school naked. Later, readers see the speaker “weep,” “sob,” and “howl” at her own childlessness after making love. A bantam hen is torn to shreds by coyotes. Within a second burning haibun, in one of the book’s more vulnerable moments, the speaker bares her neck to her mother: “You said you wanted / a daughter till you had one.”

In one of the strongest poems of the collection, greathouse circles around a memory of fishing with their father, trying repeatedly to find a way into that story, to find a name for the fear it left her with: There’s “no word for the fear of fishhooks,” but it’s not the fear of water, not of darkness, not of mirrors or of dead fish. In greathouse’s fourth and final time starting the story over again, their father has a fishhook through his palm, and “his blood—his blood was touching everything.” This image bleeds out beyond just this one poem, and the reader can see how violence has left the speaker with the specific fear named in that poem’s title: “Hapnophobia or the Fear of Being Touched.” greathouse is always circling that violence in this collection, a Medusa with a sword in hand. As she tenderizes meat alongside their mother for a family meal, she acknowledges and pushes back against the terrible fact that “any body softens / with violence.” The section ends with her reflecting upon a picture of her rapist’s wedding dress. No matter how she tries to curse it with ugly images (“failed dove” or “drying hemorrhage”), “the dress / is still beautiful. Pale & soft & pure”—and this turns out to be the most damning image of all. “Isn’t this just like my poems?” they realize. “Dressing a violence in something pretty & telling it to dance?”

▱

“I’m a one-girl armageddon,” greathouse declares near the beginning of her fourth section. Her reckless, redemptive energy in the poem is book-ended by the near-defeat in her voice in the final poem of the section: “I just want to be a question this body can answer.” Both moods are all too relatable for any body that’s been othered by those they love. This section returns to address ableism head-on, bearing down for a deathblow on the rhetorical questions from section one. Continuing to impress with their knack for marrying form and content, greathouse’s “Abecedarian Requiring Further Examination Before A Diagnosis Can Be Determined” uses the abecedarian form to effectively highlight the exhaustive examination inflicted upon the bodies we call disabled. “Antonym for me a medical / book,” they demand. “Replace all the punctuation … with question marks.”

As in “Hydrocele,” greathouse chooses again to turn to their difficult body—body “of chronic pain, my limp … blood-glittered coughs … seizures / rattling me inside my skin”—and bless it with “rituals of small mercies.” As they put it earlier in the collection, they are in the process of “unlearn[ing] lame as the first breath of / lament.” Evoking Cael Lyons’ stunning cover art, greathouse looks into a broken body and sees “the glimmer of geode.” Reading “Still Life with Bedsores,” I couldn’t stop thinking about the nauseating beauty of Kathleen Ryan’s sculptures of moldy fruit. Moving past their initial revulsion, the viewer—upon closer examination—realizes the mold is formed from precious jewels. In “An Ugly Poem,” greathouse remembers how she had “just wanted to talk pretty enough to be mistaken / for what I was.” Not anymore. She’s all rot and gemstone. “Sometimes, a strange man calls me BITCH,” she reflects. “Sometimes, this is the most woman I feel / all day.”

▱

Only seven months into 2020, the number of murdered transgendered people had already exceeded that of the previous year. In its reckoning with that grim reality, the final section of greathouse’s collection can be difficult to read. Death stares down the speaker of these poems. “The Body of a Girl Lies on the Asphalt Like the Body of a Girl” puts greathouse into conversation with Ilya Kaminsky as she refuses to reduce the horror of trans death to a metaphor. Earlier, though, she is unable to stop herself from listing out “Metaphors for My Body, Post-Mortem,” from anticipating the cruel fact that the violence inflicted on them may continue even after their death: “a toe tag / corrected; … a mother’s favorite / picture of her son; … closed casket; / endless closet;” and then, on the last line, nothing but one final semi-colon, linking absence to nothing.

greathouse begins this section, though, by reminding us that it doesn’t have to be that dramatic to be terrible. Sometime the most banal terrors are the most unlivable. In their “Litany of Ordinary Violences,” greathouse makes a list of the various aggressions inflicted upon them as they simply move throughout their town—by drunks, street preachers, shirtless men, dignified commuters, countless strangers. “Forgive me,” she asks of the reader, “I cannot find the poem in all of this.” It’s true. This “poem” is, from one view, nothing more than a list of everyday traumas—but she is compelled nonetheless to speak them, to make them “a stranger in my mouth,” to exhale them like “a breath / I don’t remember holding.”

▱

Perseus was, in the end, only able to defeat Medusa by using his bronze shield as a mirror, to track her without once having to look her in the eye. It is fitting, then, that greathouse completes their collection with “Ars Poetica, or Sonnet to Be Written Across My Chest & Read in a Mirror, Beginning with a Line By Kimiko Hahn,” a sonnet literally reversed so as to appear backwards on the page. As her statement “on the art of poetry,” it subverts what is arguably the most common poetic form, while insisting on coupling the poem inseparably with the poet’s own body. What may at first seem like a gimmick quickly impresses its meaning upon the reader as they struggle to parse out the words, their brain and eyes doing painful flips over each other to do so. The speaker defiantly draws a boundary here, declaring their body—and their body of work—their own. There’s no room here for careless observers. If you care to perceive the poem’s power—her power—it will be on her terms. It will require a mirror and a respectful acknowledgment of her body: “crippled, trans, woman,” and, most importantly, “still alive.” greathouse sums this all up in the conclusion of her opening poem:

I see Perseus’s head dangling

from Medusa’s hand & know

transition like this—to hold

a violent man’s face in your hands

to set him & his blood aside.

There’s something quite moving about standing in front of a mirror and reading this final poem, your own face—whether more Perseus or Medusa—framed beside it. Here, in a gory sort of mic drop, Medusa drops the head of Perseus and walks away, still embodied, still breathing.

Brandon Thurman is the author of the chapbook “Strange Flesh” (Quarterly West, 2018). His poetry can be found in The Adroit Journal, Beloit Poetry Journal, Nashville Review, RHINO, and others. You can find him online at brandonthurman.com or on Twitter @bthurman87.

Brandon Thurman is the author of the chapbook “Strange Flesh” (Quarterly West, 2018). His poetry can be found in The Adroit Journal, Beloit Poetry Journal, Nashville Review, RHINO, and others. You can find him online at brandonthurman.com or on Twitter @bthurman87.