A Forever Drifting Red Balloon

Review by Rachel L. Slotnick

Matthew Cooperman, “Spool”

Parlor Press

2016, 120 pages, softcover, $14

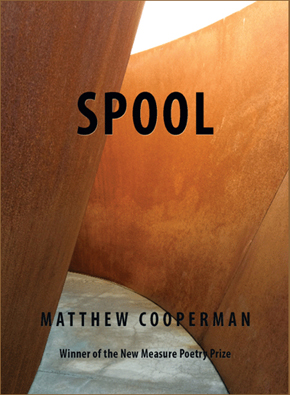

Matthew Cooperman writes poetry that simultaneously engages and disengages. His new collection, titled “Spool,” appropriately features an ominous and teetering Richard Serra sculpture on its cover, and the poems collectively follow suit. From the opening lines, we are at once drawn in and rejected by language that weathers as we read on, mimicking the mirage of rust on Serra’s outdoor installations.

Matthew Cooperman writes poetry that simultaneously engages and disengages. His new collection, titled “Spool,” appropriately features an ominous and teetering Richard Serra sculpture on its cover, and the poems collectively follow suit. From the opening lines, we are at once drawn in and rejected by language that weathers as we read on, mimicking the mirage of rust on Serra’s outdoor installations.

In every possible way, the book is divided into threes. We read three sections of poetry, and each line is constrained to three words. Consequently, the reader grasps to connect a concluding pronoun on the tail end of one thought to a hopeful verb waiting across the expanse of the margin to the next. But then after three words, the reader is expelled again, doomed to wander through the abyss of space that syphons the language into fragments of narrative. We want them to add up to something. We conjure what they might add up to. But we’re left to confront our own frustration as we teeter between recurring motifs of bees swarming through colony collapse, and a single, soft, red, balloon drifting through the wispy clouds.

The poems weave a spell that entices us to keep piecing them together. Puzzles are scattered through space and time, often reflecting on evolution itself. We travel to Avalon, the island paradise where King Arthur and other heroes were laid to rest, sometimes we awake in Ancient Illyria before the ruins were ruins, and then we blink and find ourselves amongst the Hottentrot in Southwest Africa. Occasionally, we are microscopic, cellular guardian angel proteins fighting an uphill battle against cancerous warriors. Regardless the poetry spools on, it keeps moving, as the narrative decays rapidly the harder we pull the thread. In so many ways, these poems are the literary reincarnation of Ariadne’s ball of thread, guiding Theseus through the labyrinth. Just when we think we have found our footing, and we expect the poetry’s narrative development and physical form to continue crumbling like Grecian pillars, they reform, restructure, and insist on permanency. In so many ways, they are Richard Serra’s Cor-Ten steel, teetering on the brink of collapse, but beckoning you to walk through danger.

Each of the poems are titled as Spools, and assigned a numeric identity, although of course, they follow no sequential order. Many explore etymology and evolution both on and off the page. They shift and correct themselves as they transition from encoding into internalized thoughts within the reader’s psyche: “exactly some etymology/ lurking in the trees/ author was hard/ of herding he/ saw vowels as/ substantive pets I/ like meaning but/ will take moaning.” In this stanza, Cooperman explores the human inclination to settle for the next best thing, as in our heads we read “hearing” instead of “herding,” and then stumble. Again, we read “meaning,” instead of “moaning,” and pause to question our eyes. The point is the gap between what is written and what is meant, what is hoped and what is actualized. In Cooperman’s words, “yelp of joy/ a cause of/ appearances the lies/ of the poets.” As our eyes leap across margins and search for a semblance of reward, an answer to unfurl from the wiggling dance of spinning, spooling words, Cooperman reminds us that everything is a mirage of appearances.

He fixates on process as a sort of unraveling when he evokes Serra’s famous list of 84 verbs that inspired him. They are all linked to the act of making and hint at the desperate hope of finding something tangible when the narrative concludes: “to cast to/ crease to fold/ to roll to/ bend to shorten/ to twist to/ dapple to shave/ to crumple to/ tear to chop/ to cut to/ mind to mold.” Consequently, Cooperman’s poems roll and twist and dapple and mold, as the shapes themselves morph from crumbling pillars into dancing words, from erased text evaporating into shades of gray to cross-outs hinting at past lives and reincarnation. He seems to be saying that process is all about doing and then undoing. One poem even takes the zig-zag form of a zebra, and then looks in the mirror: “things occur in/ increments half of/ a zebra my/ black and white/ lies partial sayings.” Again the poem is weaving words that are lies, yet grieves that it is missing its other half.

The poems speak to each other through mantras of inertial forces and the world’s spindle. They beg for evolution and they struggle to see straight as Cooperman weaves Middle English into Spanish and Portuguese. They reference “bee belief” while they question the hive, then they go blind: “I am beginning/ to see and/ continuing to see” is followed by a stanza in which the text fades to a nearly invisible gray. Elsewhere, French decays into a spray of water as Cooperman spools, “on a slide/ in a dream/ La Poudre spring/ run off the/ rack of a/ moose emerging from/ the river/ a.” As we watch the moose of our dreams emerge from a secret underwater world, and we envision a rising crown of antlers lighting the poem like a sun, we almost don’t even notice that for once, Cooperman has strayed from the form of the spool, allowing two words to occupy an entire line, followed by a single vowel, at once a poet’s lie, an identifying article, and a single red balloon floating above the landscape.

Craving resolution, I look back to the beginning for a semblance of circumference. Have we been here before? Cooperman opens not on Spool 1, but on Spool 16, “time is honey/ and honey pain…to ask questions/ to want answers/ a red balloon/ caught in the elms.” I can’t seem to shake that balloon from my memory, an isolated vowel hovering in the clouds, even as the collection sets under a lavender sky: “blood colored hyacinth/ part enigma part/ body that obliterates/ verses were the/ murex that dyed/ all existence purple.” He closes “word for wood” again taunting our desire for meaning as he likens language to sculpture. Poems become spheres, planets, cells, all things spooled, and the bolded letter “O” dominates closing stanzas: a shape we remember form our childhoods at the beginning of the narrative, a forever drifting red balloon.

Rachel Slotnick received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and she is a professor at Malcolm X College and adjunct faculty at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work has appeared in Mad Hat, Thrice Fiction, Driftwood Press, and elsewhere. Slotnick won Rhino Poetry’s Founder’s Prize and was nominated for the Pushcart Prize in 2015. She is the author of “In Lieu of Flowers,” available through Tortoise Books.

Rachel Slotnick received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and she is a professor at Malcolm X College and adjunct faculty at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work has appeared in Mad Hat, Thrice Fiction, Driftwood Press, and elsewhere. Slotnick won Rhino Poetry’s Founder’s Prize and was nominated for the Pushcart Prize in 2015. She is the author of “In Lieu of Flowers,” available through Tortoise Books.