Refresh, Rewind: Human Truths

in Josephine Yu’s New Collection of Poems

Review by Dorothy Chan

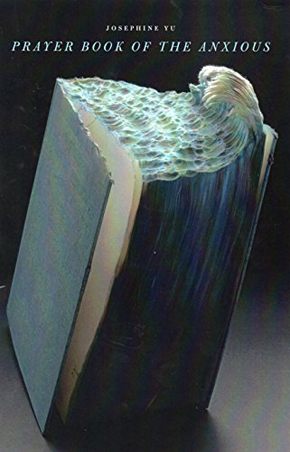

Josephine Yu, “Prayer Book of the Anxious”

Elixir Press

2016, 96 pages, softcover, $17

In “Prayer Book of the Anxious,” winner of the 15th Annual Elixir Press Poetry Award Judge’s Prize, Josephine Yu invokes the reader in a Whitman-esque way. Readers are forced to face their own truths and falsehoods, by experiencing those found in the lives of Yu’s speakers. Yu’s speakers make us confront ourselves. In the end, we are all part of this Prayer Book of the Anxious because we all yearn, though we are sometimes afraid of expressing our deepest longings. In other words, Yu’s “Prayer Book of the Anxious” unites us since we all experience anxiety and worries and we all aim toward our dreams and longings. It is this vulnerability that makes us human; thus, even Yu’s speakers that lie end up representing truth—human truth.

In “Prayer Book of the Anxious,” winner of the 15th Annual Elixir Press Poetry Award Judge’s Prize, Josephine Yu invokes the reader in a Whitman-esque way. Readers are forced to face their own truths and falsehoods, by experiencing those found in the lives of Yu’s speakers. Yu’s speakers make us confront ourselves. In the end, we are all part of this Prayer Book of the Anxious because we all yearn, though we are sometimes afraid of expressing our deepest longings. In other words, Yu’s “Prayer Book of the Anxious” unites us since we all experience anxiety and worries and we all aim toward our dreams and longings. It is this vulnerability that makes us human; thus, even Yu’s speakers that lie end up representing truth—human truth.

Yu’s opening poems, “The Compulsive Liar Apologizes to Her Therapist for Certain Fabrications and Omissions” and “A Myth from the Palm-Leaf Manuscript” epitomize this human tendency to lie due to vulnerability. Yu is unabashed in her labeling of the collection’s many personas—the speaker of the first poem is outright called a “compulsive liar” while the story takes place at her therapist’s office. The “compulsive liar” narrates:

When you asked about my marriage, I lied. My job,

that too. When you asked for a dream, I confess

I gave my mother’s, the one that woke her coughing,

thinking she’d choked on her sister’s tangled, hip-length hair.

Truth is, I’m an only child.

It is so telling that the “compulsive liar” gives away her mother’s dream—this choice adds to the critical line, “Truth is, I’m an only child.” Some dreams are simply too extraordinary to reveal, and we end up not telling them and instead rely on our parents to comfort us as if we are children. We are all made up of many personas, and the persona of our childhood self is one that perhaps never goes away in times of vulnerability. On another note, Yu’s blatant labeling of the first speaker as a “compulsive liar” is one of the book’s many appeals. As a reader, I love Yu’s refreshing directness and her ability to spin life lessons in a contemporary, even snarky way. But above all else, Yu is sympathetic to the human condition. Her second poem, “A Myth from the Palm-Leaf Manuscript,” sets the stage in a different way—whereas Yu talks to the reader through the “compulsive liar” of the first poem, in this second poem, Yu directly addresses the reader through second person: “Make her you, you ten, her husband your father, before the divorce.” Yu explores how the palm-leaf manuscript brings people together—we each may have our own story to tell, or our own history to interpret, but despite our different backgrounds and narratives, pain is pain, and love is love. If a palm-leaf manuscript gives us a history, we must acknowledge how that history is applicable to so many people.

Yu models this human applicability through the presentation of her poems—she is a genius in curating poetic pairings. After all, Yu is giving us a “prayer book of the anxious,” where every “anxious poem” needs an accompaniment for calming. “The Fortune Teller Knows She’ll Never Marry” and “Veneration of the Anxious” is one of the strongest pairings of the book’s first section, titled “Apologia.” As proven with the opening poem, Yu is a master of titles, and “The Fortune Teller” is no exception to this rule. A beautiful detail in “The Fortune Teller” lies in the opening:

Because she wakes one morning with hands

so swollen even her father’s class ring

can’t be worked over the stiff knuckle.

Here, Yu presents a paradoxical situation: the fortune teller, an “objective” woman who represses emotion is physically vulnerable, which makes the reader wonder how much of the “swollen even her father’s class ring / can’t be worked over the stiff knuckle” relates to anxiety. Yu then couples this subtle yet visceral scene with the next stanza’s dialogue, in which the fortune teller foretells (to a client, the “hopeful woman”): “You give your love too easily, / you toss it like pennies into a well.”. This dialogue becomes an overall indication that vulnerability isn’t giving up or letting go anytime soon. Thus, “Veneration of the Anxious” serves as a strong follow-up to “The Fortune Teller.” Just as the reader wonders about the fortune teller’s “swollen” finger and what is “consecrated,” the reader also ponders the relationship between “grief” as a “motel,” and “worry” as a “cathedral.” Yu successfully brings out the theme from “The Fortune Teller” in the last stanza of “Veneration of the Anxious”:

We come to be consecrated

in dizziness, nausea, insomnia,

ecstatic to hear the chorus of heartbeats,

those hymns racing.

Yu solidifies what is holy in what is human. We are holy because of our “dizziness, nausea, insomnia.” We are holy when we are ecstatic. We are even holy when we cannot come to terms with the truth of our desires—Yu’s collection serves as an antidote for us to face those desires head-on, and speaking of confrontation, Yu pushes directness even further with “A Vindictive Son of a Bitch of a Poem.” Here, Yu merges self-discovery with ars poetica:

If you’re expecting a moment of redemption

or a metaphor or anything other than the sound of my house key

squealing across the passenger door of her Jetta,

I’m sorry to disappoint you, but you’ve got the wrong poem.

In translation, Yu is telling us poets: don’t be apologetic. This lack of apology along with the poem’s humor and the ending, which emphasizes the poem as human and human as the poem, makes “A Vindictive Son of a Bitch of a Poem” a must-read. Again, Yu brings the ars poetica theme in this conclusion:

Or maybe its father just died

and realized it will never be half

the poem he was.

Yu follows the first section of “Apologia” with the section, “Canticles Maybe.” “A Fable from the Palm-Leaf Manuscript” is a standout poem of “Canticles Maybe” because, like “A Vindictive Son of a Bitch of a Poem,” it questions conventions in poetry. By labeling her poem a “fable,” both Yu and the reader question the moral in the story recounted: “If this is a fable, what is the moral? What animal am I? What glass jar will fill with rain, raising what berry within my reach?.” It’s charming how Yu’s speaker questions the moral of the fable as if she’s also an active reader of the poem. This pattern brings the fable full circle as the motif of the palm-leaf manuscript is explored again.

Another critical strength of the collection lies in Yu’s refreshing awareness. “Middle Class Love Song” best represents this refreshing quality. I also must emphasize that Yu is a master of the couplet—she truly brings out the form’s delicate nature through her mixing of high and low: “to catch a matiness at Miracle 8 or grab a venti from Starbucks, / and ok, our rental looks kinda trashy, the jasmine vine dying / on the chain-link in a gothic brown tangle—poisoned, we think, / by our duplex neighbor’s latest crazy ex—but we’re rich in.” Yu approaches the couplet with such mastery, allowing the lines to sensuously enjamb with references. And to emphasize the idea of a “middle class love song” even more, Yu ends with:

and our children’s children will have ever-increasing latte options

and even richer neighbors and even crazier, more creative exes.

With this, Yu allows the ending to hark back to the title. As a result, this poem, like many others in the collection, follows a round. Yu’s final section of the book, “Rustle of Offerings” further takes this “circling back” concept. By starting the final section with a poem titled “When We Have Lived for Thirty Years in One Town,” Yu further emphasizes the “circling back.”

“Useless Valediction Forbidding Mourning” is the beauty of Yu’s final section. This poem pays homage to classic poets, yet in Yu-fashion, the speaker contemporizes the heartbreak. Lines like “its phrase book of conversational heartbreak” take us back to the “prayer book of the anxious.” I love the poet’s synesthesia—with these phrases on the tip of our tongue, our heartbreak is not only extended but also made more precious. The “fumbling through” is so vulnerable, so relatable, and so precious without being sentimental. And just before we even question the sentimentality of the poem, Yu pulls us out with another ars poetica moment: “Oh, but the heart isn’t fooled / by the gorgeous lies of poems.” These final lines make the reader question the truth in poetry.

Speaking of truth, Yu closes her gorgeous collection with “Never Trust a Poem that Begins With a Dream,” which serves as a remarkable bookend to the first poem. In this collection, we build our trust of the speaker through lines such as “Some nights he’s the boy you had a crush on in eighth grade,” “Peter Pan-collared Catholic school girl / blouse you wore un-ironically, being a Catholic school girl.” As evident in the previous poems, Yu’s speakers are witty and down-to-earth, easing us through every part of the collection as we build our own Prayer Book of the Anxious.

Dorothy Chan is the author of “Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold” (Spork Press, 2018) and the chapbook “Chinatown Sonnets” (New Delta Review, 2017). She was a 2014 finalist for the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship, and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Blackbird, Plume, The Journal, Spillway, and others. Chan is the Assistant Editor of The Southeast Review.

Dorothy Chan is the author of “Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold” (Spork Press, 2018) and the chapbook “Chinatown Sonnets” (New Delta Review, 2017). She was a 2014 finalist for the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship, and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Blackbird, Plume, The Journal, Spillway, and others. Chan is the Assistant Editor of The Southeast Review.