Learning the Art of Love:

On Larissa Pham’s ‘Pop Song’

A review by Meredith Boe

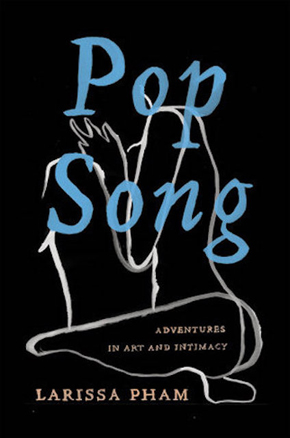

Larissa Pham, Pop Song

Catapult, 2021

288, Paperback, $28

In his 1956 book, The Art of Loving, social psychologist and philosopher Erich Fromm wrote that “love is an art, just as living is an art.” He thought that we should approach learning to love as if we were learning to play music or paint. The idea is at once suspect and hopeful, especially for those of us so often overtaken by intoxicating love affairs that eventually dwindle into piles of excruciating disappointment. If love is an art to be crafted, maybe we have more control than we think and are not always destined to succumb.

In his 1956 book, The Art of Loving, social psychologist and philosopher Erich Fromm wrote that “love is an art, just as living is an art.” He thought that we should approach learning to love as if we were learning to play music or paint. The idea is at once suspect and hopeful, especially for those of us so often overtaken by intoxicating love affairs that eventually dwindle into piles of excruciating disappointment. If love is an art to be crafted, maybe we have more control than we think and are not always destined to succumb.

Larissa Pham links love and art similarly yet a bit more subtly in her stunning debut essay collection, Pop Song: Adventures in Art and Intimacy, carrying us through the tensions of youth and the influence of surroundings. She writes with the conviction of a lover and the grace of a painter. Pham’s essays are written to an unnamed “you,” who is a man she was in a relationship with. She evaluates the emotional buildup to their first meeting, then frames their push and pull, ending with a reevaluation of the self after their relationship ends. Along the way, Pham encounters works by Agnes Martin, Nan Goldin, Jenny Saville, Louise Bourgeois, and other artists, describing the links between love, art, and pain in her own beautiful portraits of womanhood.

The book’s opener, “Running,” mostly takes place when the author was an undergrad at Yale. Pham attempts to accept how jagged her early twenties were, how what she wished she could become always felt unattainable, by examining the act of running: “Running is predominantly punishing: it ruins your knees, wrecks your ankles, and causes shin splits.” Pham sets up subsequent themes in the collection here, showing that the act of running is not dissimilar to love or life.

She says she had fantasized about becoming a runner who was “a happy ascetic,” as if the daily chore of it could liken her to a Buddhist nun, “wishing I could be as true and neat as an arrow.” Readers learn early on that she was often too overcome with desire, seeking out sensations and experiences, even painful ones, in order to obliterate the anxiety of living.

Similar to experimenting with running, spending time writing alone in Taos, New Mexico, has a major impact on Pham. She writes about the landscape and the artists who sought its inspiration before her, and what it means to look for something specific and find something else entirely. By setting aside space and time to write, she is “trying to close that gap between the mess of my own life and its interpretation.”

During this time, she particularly resonates with Agnes Martin’s paintings that were created using a grid, like “Wood” or “Stone,” both paintings from 1964. Pham says, “If you stand back you see one thing and if you get close you see another, and all it takes is leaning forward to fall into the details of how it’s made and what it says.” Pham uses the act of looking at a painting as a metaphor for self-reflection and self-acceptance and considers the human tendency to contract different meanings for oneself based on someone else’s intentions.

Pham’s striking essay “Body of Work” describes the emotional pain humans have a capacity to retain by considering Nan Goldin’s “Heart-Shaped Bruise,” a photograph of a woman’s leg bruise that is “defined by its outline.” When pain is visible on the body, it can act as a constant visual reminder, and perhaps makes it easier to come to terms with. However, the types of pain that Pham experienced—an eating disorder, mental health struggles, continued questioning of self-worth—were harder to identify and construct and thus harder to work through.

In the same essay, Pham also wonders whether the men she sleeps with are using her. After engaging with philosophy texts, she finally feels more empowered to look inward: “I began to consider my own Asian-Americanness… finally acknowledging the effects of being a repeatedly colonized subject—the ways women who looked like me had been degraded and degraded.”

These revelations relate to her then diving into the world of BDSM, loving how it helps her “relinquish control,” and she starts to crave that pain, that escape. She works for a time at a call center responding to and supporting victims of violence and sexual abuse, herself being a victim. Even when she finds someone she wants to trust, her “body refused to stop thinking it was in the presence of a threat.” She struggles to reconcile her desire for love with her tendency to shut out parts of herself she can’t confront. Learning to love the mind and body that one must live with is often the hardest step of all.

These meanderings about love, expression, and obsession seem to culminate in the essay “Crush,” which considers why we might use such a violent term for a fantastical, often innocent feelings of love and obsession. Pham cites Eros the Bittersweet by Anne Carson, who noted that when we have feelings of erotic desire, “alongside melting we might cite metaphors of crushing, bridling, roasting, stinging, biting, grating, cropping, poisoning, singeing and grinding to a powder.” Pham read these words and accepted “what they wager… it seems like a reasonable exchange for something destined to interrupt my body anyway. Go ahead and grind me to powder: it hurts to wait.”

But once you let yourself be devoured, what happens then?

Pham wonders how to do anything without losing the self. Her essays are about distance— the distance of longing, the distance of a crush, the distance of an artist’s intention. Pham says:

When I say I have a crush on you, what I’m saying is that I’m in love with the distance between us. I’m not in love with you—I don’t even know you. I’m in love with the escape that fantasizing about you promises.

Here, distance frames perception, in which fantasy is in constant tension with reality. Pham helps us see how easy it can be to believe that artists and people we idolize have the solutions to our problems.

“Camera Roll (Notes on Longing)” describes how Pham is motivated to create art to consider this part of her identity more deeply. She took photographs of “you” early on in their relationship. She says that in taking pictures, she didn’t know if she was trying to capture this person as he truly was, or to capture him as she saw him.

Pham invites readers to consider how we communicate with audiences and lovers. She interacts with Marshall McLuhan’s ideas and wonders how much is lost each time something is translated:

The message of any medium is simply another medium, McLuhan suggests. Written text carries speech; speech carries thought; thought itself is one of many nonverbal processes, the language for which we are always grappling.

Even writing about an artwork loses something in translation that Pham mourns. But we accept these gray areas as places to assign meaning to our own lives. Perhaps things getting lost in translation is the point, not the problem.

Sometimes her preferred method of communication is through touch, through sex. Pham writes: “How often have I thought, If I could just touch you, I could make myself legible to you?”

Pham also tries invoking the modern love letter: a shared Instagram account she and her lover use when she is away or they aren’t speaking. Each image is a “dark vessel” with hidden meanings only they will understand. Even the sharing of art is a form of communication, digging through our own perceptions and our assumptions about others’ perceptions until we unearth connection.

In “On Being Alone” Pham seems to accept that sometimes interacting with so much art, and pinning your feelings on others, gets in the way of growth; that sometimes they are distractions from self-love and self-actualization. It’s in this essay that she finally lets herself “think to the very end of every thought, every catastrophic possibility,” instead of fearing grief itself.

The work of French-American sculptor, painter, and printmaker Louise Bourgeois is on exhibit at the Long Museum in Shanghai while Pham happens to be there on a work-related trip. One of Bourgeois’ installations, Hours of the Day, includes a series of hand-sewn panels, each with a clock representing a different time of day and accompanying text, mirroring “that acutely frantic, anxious feeling of being caught in one’s own head,” as Pham reflects. She feels at home looking at the panels and “witnessed by her poetics,” and is moved by how willing Bourgeois was to reveal her voice.

She says, “Bourgeois was an artist of the body, of trauma and personal history,” whose work was “the opposite of safe: it teemed with an uncanny psychological energy, vibrating with the pain of the interior.” Bourgeois said herself that she wanted to “give meaning and shape to frustration and suffering.” And yet, Bourgeois offered no solutions, no remedies in her work. Only a replica of what pain feels like, and not from a distance.

As Bourgeois wrote in one of her panels: “Your sudden perception of beauty / is what keeps you going / step by step along the way.” Pham’s beautifully candid essays in Pop Song remind us that through the fraught, delicious gray areas that art and love provide, we uncover ourselves again and again.

Meredith Boe is the author of the chapbook What City (Paper Nautilus) and her work has appeared in the Chicago Reader, Chicago Review of Books, After Hours, Mud Season Review, Midwestern Gothic, and elsewhere. She lives in Chicago.

Meredith Boe is the author of the chapbook What City (Paper Nautilus) and her work has appeared in the Chicago Reader, Chicago Review of Books, After Hours, Mud Season Review, Midwestern Gothic, and elsewhere. She lives in Chicago.