Extracted from the Narrative Lattice

A review by Kelly Krumrie

Fleur Jaeggy (tr. Gini Alhadeff), The Water Statues

New Directions, 2021

96, Paperback, $13.95

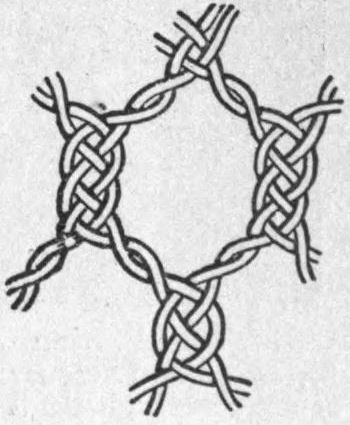

The best adjective I can think of to describe this novel is “lacy.” The word itself is used a few times, but The Water Statues contains a phrase more apt: “rope endowed with reason.” Whether lace or rope, sentient or not, what I mean is thready and tight, something interlocking but with gaps and distance, an airiness that makes me a little anxious. By distance I mean the way you look at lace, how close to your face you hold it. Do you see pattern or joins? Representation or form? A few of the characters in The Water Statues embroider: Is the novel the front or the back of the work?

The best adjective I can think of to describe this novel is “lacy.” The word itself is used a few times, but The Water Statues contains a phrase more apt: “rope endowed with reason.” Whether lace or rope, sentient or not, what I mean is thready and tight, something interlocking but with gaps and distance, an airiness that makes me a little anxious. By distance I mean the way you look at lace, how close to your face you hold it. Do you see pattern or joins? Representation or form? A few of the characters in The Water Statues embroider: Is the novel the front or the back of the work?

When I think of Fleur Jaeggy’s fiction, her novels Sweet Days of Discipline and S.S. Proleterka come to mind with their crisp prose; disillusioned adolescent protagonists; paratactic sentences; unreal rendering of the real via the texts’ subtle acknowledgments of themselves, or acknowledgment of artifice via parataxis which I’d argue creates a compact adolescent point of view; not much dialogue (in the traditional sense); and an unapologetic manipulation of or disregard for “narrative” (whatever that means). (For a thorough explication of her style and work, including this recent publication, I recommend Dustin Illingworth’s Wintry Moods in New Left Review.) All of this comes to play in the 1980 short novel The Water Statues but a little differently. In a way, it’s very unlike her other books, and in several ways like many other things, and mostly, overall, if you press me to say it, unlike anything else.

Let’s begin by looking at the big picture: The novel is 89 pages; it begins with DRAMATIS PERSONÆ. There are two parts of roughly equal length. Each part is comprised of short prose segments, from about one paragraph to three pages. Some segments begin with a character’s name and a colon, structured, via this formatting, as short monologues, but not always: others speak within the blocks of speech, in the present moment or as quoted speech from memory, sometimes creating such removal that you forget it’s embedded in another speaker’s speaking. Speakers describe their environments and what they’re doing kind of clunkily and unrealistically—meaning, I don’t typically say aloud that I’m walking into another room. Here, inside speech: “I go up the stairs” or “Now they are making dinner.” These moves pull the reader out—I’m extracted from the narrative lattice. And also getting ahead of myself.

Let’s begin by looking at the big picture: The novel is 89 pages; it begins with DRAMATIS PERSONÆ. There are two parts of roughly equal length. Each part is comprised of short prose segments, from about one paragraph to three pages. Some segments begin with a character’s name and a colon, structured, via this formatting, as short monologues, but not always: others speak within the blocks of speech, in the present moment or as quoted speech from memory, sometimes creating such removal that you forget it’s embedded in another speaker’s speaking. Speakers describe their environments and what they’re doing kind of clunkily and unrealistically—meaning, I don’t typically say aloud that I’m walking into another room. Here, inside speech: “I go up the stairs” or “Now they are making dinner.” These moves pull the reader out—I’m extracted from the narrative lattice. And also getting ahead of myself.

The first part of the novel concerns a young man (age is a little ambiguous here) called Beeklam, his servant Victor, Beeklam’s widower father Reginald, and Reginald’s servant Lampe. Beeklam and Lampe are the most Beckettian names I’ve ever read outside work by the man himself. And bear with me re extending this idea of “thread,” but we wouldn’t be wrong calling this novel “Beckettian” (I confess to being a stickler with regards to that particular descriptor, a Beckettian purist or something). Think of “Ill Seen Ill Said” or short prose from the late ‘40s: we’ve got some back and forth walking, and the narrative and characters stutter among boulders and bodies of water. Everyone’s little ghostly. Back to it: Beeklam’s mother dies, he moves to a house, hangs out in the basement, and thinks about his collection of statues, water in the walls, and drowning. Victor is his only friend (except for his own reflection and the statues), and friends are doubled: for example, Victor and Lampe are basically indistinguishable. Each of the characters wants “company”—cue Beckett again.

Beeklam is a strange adult-child, robotic (statue) but sinuous like the doll in Stacey Levine’s short story The Doll. Beeklam is doubled in part two by an adolescent girl called Katrin (her appearance was a relief to me as I secretly hoped to find another Sweet Days). Katrin minds a sundial; other figures and voices circle her. I’m constellating: Marie Redonnet’s Forever Valley and its pits, rocks, mountains, and reservoir… Everyone in The Water Statues is drowning in what the book jacket calls “icy” prose (Beckett, Levine, Redonnet)—but what does icy mean? Short sentences? Crisp word choice? No flourish? Jaeggy manifests a kind of blankness in this work. See, for example, from her recent interview in The New Yorker: “I’m mostly nothing, you see?”

If you read this book, you might need to surrender to form, to hold the lace to your eyes and not mind.

The Water Statues is polyvocal in that there are many voices and purgatorial in the fact that everyone’s waiting (in basements, in rooms with cracked windows, on benches, in a botanical garden). The movements and stillnesses of the figures, rendered as they are, feel more like a Bruguière photograph than a novel: superimposed and blurry. For example, between monologues there are moments such as

“The shadow of a long index finger, thin as the sound of a music box, appeared on the wall.”

which serve as cinematic removals from characters’ uttered interiorities. This is what I meant by removal earlier. If this were Beckett, we’d be trapped in consciousness. Instead of running thoughts (in a skull, he’d be sure to clarify), we see—via the formatting—that speech is speech, and some of it isn’t, and all is really just text. The dramatic form pulls the reader out to the novel’s artifice. It makes no attempt to render “life” outside the one invented by the stilted perceptions of the novel’s speakers and third person description (or perhaps Jaeggy herself).

And if the figures are a little purgatorial, life isn’t where they are. There are talking crows and drunk snails. Beeklam and I are both statues. We’re not far from Nathalie Sarraute’s “Tropisms” either. I don’t mean any of this as criticism but as something to know. I think we might abandon expectation of narrative—and even setting—and find pleasure in this manifestation of abstraction: how we move through time and space before and between life and death. It’s a strange cast of who and what we surround ourselves with in grief—what company we keep.

Though this novel was originally published in 1980, I find its push away from contemporary fiction so refreshing, a real fuck you to our understanding of the novel, no matter how formally playful or genre-bendy we make ourselves out to be—and without messy maximalism or sharp wit (though this book has edges). All I can really say is I wish I had written this, and I wish there were more novels like it, even at the risk of making The Water Statues less singular.

Kelly Krumrie‘s first book, Math Class, is forthcoming from Calamari Archive in 2022. Other creative and critical writing appears in journals such as Tarpaulin Sky Magazine, Annulet, DIAGRAM, La Vague, and Black Warrior Review. She holds a PhD in English & Literary Arts: Creative Writing from the University of Denver.

Kelly Krumrie‘s first book, Math Class, is forthcoming from Calamari Archive in 2022. Other creative and critical writing appears in journals such as Tarpaulin Sky Magazine, Annulet, DIAGRAM, La Vague, and Black Warrior Review. She holds a PhD in English & Literary Arts: Creative Writing from the University of Denver.