The Double Loss of a Former Home:

An Interview with Neema Avashia

by Margo Orlando Littell

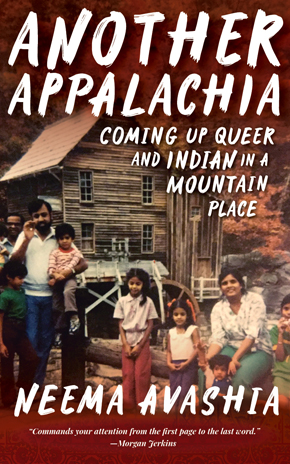

Is home the place you live, or the people you love? What happens when a home you love doesn’t love you back? In her memoir “Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place,” essayist Neema Avashia explores her complicated connections to her West Virginia hometown, where she grew up in a tight-knit community of Indian immigrants forging a new version of Appalachia. Many years later, Avashia has built a life in Boston; most of her loved ones have left West Virginia; and racism and homophobia stain the community that once embraced her. The essays in this collection reveal the relentless, often painful push-pull of connection to and rejection of the place that has shaped Avashia in so many ways—an Appalachia that few people see, let alone understand and claim. Avashia talked to Margo Orlando Littell about loss, ritual, and the threads that link past to present no matter where we live.

Is home the place you live, or the people you love? What happens when a home you love doesn’t love you back? In her memoir “Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place,” essayist Neema Avashia explores her complicated connections to her West Virginia hometown, where she grew up in a tight-knit community of Indian immigrants forging a new version of Appalachia. Many years later, Avashia has built a life in Boston; most of her loved ones have left West Virginia; and racism and homophobia stain the community that once embraced her. The essays in this collection reveal the relentless, often painful push-pull of connection to and rejection of the place that has shaped Avashia in so many ways—an Appalachia that few people see, let alone understand and claim. Avashia talked to Margo Orlando Littell about loss, ritual, and the threads that link past to present no matter where we live.

The closest approximation of faith for me might be the omnipresent pull to go home to the Mountain State.

—page 92, “A Hindu Hillbilly Elegy”

MARGO ORLANDO LITTELL: In the essay “Wine-Warmth,” you talk about what could be called versions of homesickness—hiraeth, the Welsh word for “nostalgia”; vatan, Gujarati’s “homeland”; and saudade, “nostalgia for what is lost.” These ideas are woven throughout the collection, and a multilayered longing for your own homeland—West Virginia—underscores this work. How much does your writing rely on your distance from home? Is there any context in which you could write about Boston, your current home, with similar depths of feeling?

NEEMA AVASHIA: I think distance from home has been profoundly necessary for me to be able to both process the hard parts of my Appalachian upbringing, in terms of racism and the invisibility of queerness, and to fully appreciate the wonderful parts of that place and my time there. I’ve lived in New England now for almost as many years as I lived in West Virginia, and while I certainly have deep feelings about this place, they are much messier and more conflicted than my feelings about WV. I don’t have distance on what’s hard about the place where I live now. I feel the things that are hard about it—the literal and emotional coldness, the inability to be honest about structural racism, the ways in which it is deeply segregated—daily, and those are the things I find myself writing about the most.

My mom waxes nostalgic about doing Navratri garba for all nine nights growing up in India. I only know the experience of two weekend garbas held in the same middle school gymnasium where I took phys ed from Monday through Friday.

—page 92, “A Hindu Hillbilly Elegy”

LITTELL: The idea of ritual is both straightforward and complicated for your Indian friends and family in West Virginia. Straightforward in that the rituals themselves are consistent across time and space; complicated in that you, as an adult, recognize a kind of dislocation in where and how the rituals play out. I love how you describe this in “A Hindu Hillbilly Elegy”: “We had modified rituals, simulations of holidays, held in incongruous spaces with fluorescent lighting and shiny linoleum flooring.” You grow up experiencing ritual as shallow; yet in adulthood, you reach for your family’s rituals in times of grief and crisis. How do you explain the enduring power of these dislocated rituals?

AVASHIA: I think rituals are a huge part of processing key moments in our lives—both the joyful moments, and the hard ones. One of my struggles in adulthood has been feeling like the rituals I grew up with don’t fully align with my present-day identity, but at the same time, there is not another clear set of rituals to opt into. In some cases, primarily joyful rites of passage, I’ve been able to work with my partner, Laura, to create a set of rituals that is meaningful to us. In others, particularly in moments of deep grief, it’s been difficult to see my way clear to new rituals, and so I’ve found myself defaulting into the old ones. Not necessarily because they bring me deep peace, but rather because I feel the need to do something, and the only thing my brain knows how to do, the thing that is most automated, is that old ritual. I think our bodies gravitate toward ritual as a way of working through moments when our brains are too overwhelmed to think clearly. The act of doing is its own salve, in some ways, even if the thing we are doing doesn’t bring us full comfort.

While the hills of West Virginia shaped me into the person I am today, I have passed beyond them, my shallow roots trailing behind me as I go.

—page 159, “Only-Generation Appalachian”

LITTELL: Despite the political clash, despite the overt racism and homophobia you’ve witnessed and experienced, despite the insensitive social media posts from loved ones who don’t share your worldview, and despite the fact that your family no longer lives there, West Virginia remains integral to your idea of home. The natural beauty of this part of the world still draws you in, an affecting holdover from your childhood. “Home isn’t a place,” says your mother in “Wine-Warmth.” Can you talk a little about why you agree or disagree?

LITTELL: Despite the political clash, despite the overt racism and homophobia you’ve witnessed and experienced, despite the insensitive social media posts from loved ones who don’t share your worldview, and despite the fact that your family no longer lives there, West Virginia remains integral to your idea of home. The natural beauty of this part of the world still draws you in, an affecting holdover from your childhood. “Home isn’t a place,” says your mother in “Wine-Warmth.” Can you talk a little about why you agree or disagree?

AVASHIA: I think my mom and I have profoundly different life experiences that make us think about the idea of home differently. She left her home at the age of nineteen to move to a country where she knew no one other than my father. For her, the pull of “home” has often been a pull backward to her family in India, a pull that I understand, but don’t totally share. For me, there is something about growing up in Appalachia that has made place as much a part of my understanding of home as people are. When I think about the idea of home, places in West Virginia persist in my mind even as the people who populated that place for me have moved away, or passed on. Which is to say, I think I will always go home even if there aren’t people I’m going home to. For a long time, I thought this was just a strange quirk of my nature, but the more I read Appalachian writers, and the more I see place manifest as a character in its own right in their writing, I think this may just be part of what it means to be Appalachian—home is place and people, not people alone.

Perhaps my writing just provided the ultimate justification for an excommunication that had been years in the making.

—page 124, “Shame-Shame”

LITTELL: Your family’s response to your writing has been fraught, leading to broken relationships and painful confrontations that you describe in “Shame-Shame.” Speaking truthfully and speaking publicly are vastly different—one queasily accepted, one absolutely renounced. You remark that you “shared stories that weren’t [yours] to share.” Yet discretion and privacy aren’t so far removed from secrecy. In which area do you feel your writing lives? Do you feel your work is rooted in family secrets? And, if so, how would you define “secrets” in this context?

AVASHIA: I think that secrecy and shame are very tied together. Which is to say: because we are ashamed of things, we keep them a secret. But I question who those secrets benefit, and who they do a disservice to. And I wonder if sometimes keeping secrets means that we end up upholding oppressive systems and behaviors, instead of bringing them into the light. As someone who grew up in the context of a lot of silence and shame, all of which made it harder for me to parse my own identity, I think I’ve come to the conclusion that secrets don’t serve us; they harm us. I’ve tried really hard to learn from the mistakes of my early writing, and to make sure that my mistakes, my struggles, my questions are at the center of this collection, and that I am the person most implicated at all times. But certainly, sometimes my questions are about the secrets we keep, and the shame we bear, how those secrets and shame shape the way we orient toward the world. And I’m braced for there to be some blowback from people who would rather I say, and write, nothing at all. But culturally, our silence about issues of mental health, about gender inequality, about racism and classism and homophobia—it isn’t serving us. In fact, it is harming us in profound ways. And I don’t want to be quiet about it.

There are Americans whose ancestors have lived in the same state for centuries who don’t always know as much about their states as I do. This is a fact. And it is also a fact that knowledge is not the marker of belonging in America that I want it to be.

—page 136, “Our Armor”

LITTELL: In “Our Armor,” you talk about your mother’s proud wearing of traditional Indian attire in her everyday West Virginia life, how “she opted to own her foreignness.” Later in the essay, you say, “I can’t remember when I began to openly flaunt my West Virginia roots.” By doing this as a professional in deep-blue Boston, you position yourself as a different kind of outsider, challenging and upending urban liberals’ stereotypes of Appalachia generally and West Virginia specifically. Both as a child in West Virginia and as an adult in Boston, you’ve forged deep connections to places where others might assume you don’t belong, or accuse you of not belonging. Can you speak to this tension, and how it has shaped your idea of home? It’s interesting to me that you’ve carved out pockets of warmth and welcome in unexpected ways and places.

AVASHIA: I think that for me, home has always been represented by the relationships and places within which I’ve been able to express the most authentic version of myself. So did all West Virginians embrace and accept me? Definitely not. I have the scars to prove it. And do all Bostonians view me as belonging here, despite me having lived here for close to twenty years? Certainly not. We just finished a mayoral election where an Asian-American candidate’s qualifications were undermined because she wasn’t “from here,” though she’s lived here as long as I have. But in both spaces, are there people who love and embrace my intersectionality, who understand that people can be more than just one thing, and that the things that comprise a person’s identity can seem contradictory from the outside, but entirely make sense within their cohesive embodiment of self? Most definitely.

I remember reading Walt Whitman’s “Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes,” in high school and grabbing onto it as the earliest glimmer of what intersectionality might mean, and then continually seeking out spaces where that kind of contradiction was embraced.

More and more, I think I gravitate away from spaces where people hold only one identity as primary, and toward spaces where we are able to show all the different parts of ourselves, and talk about the ways in which different parts of ourselves might show up more strongly in one context or moment than they might in another. And frontloading the most complicated or contradictory aspects of my identity has become a way of pressure-testing what people are able to hold. Can you get down with a loud, queer, Indian, Appalachian, politically radical public school teacher who nerds out just as hard about Jhumpa Lahiri’s writing as she does about Queer Eye on Netflix? If no, keep it moving. If yes, be prepared for me to love you hard, and for you to end up loving me pretty hard in return, because I’m pretty darn lovable.

I once viewed my father’s ethics as the ethics of community. Now I wondered if in fact they had been the ethics of assimilation, or the ethics of survival.

—page 19, “Chemical Bonds”

LITTELL: Your father, a doctor, worked for Union Carbide in West Virginia, and used his medical background to help his neighbors with checkups, flu shots, and prescription drugs procured cheaply from India. You describe this neighborly helpfulness as the “ethics of place,” a requirement of being a respectful, and respected, member of a community. Going above and beyond was a way of life. Have you ever recognized “ethics of place” in other places you’ve lived, or do you feel this was/is distinctly West Virginian?

AVASHIA: I have to say that this is something I’ve spent my entire adulthood chasing, but haven’t found in any other place I’ve lived: not Pittsburgh, not Madison, WI, and not Boston. That willingness to see—really see—and serve others, and to be seen and served in turn, is just not evident on a large scale outside of West Virginia, in my experience. I have tried to live out that ethic in my own life, with my partner, my neighbors and friends, and have had varying levels of success. My partner Laura certainly gets it, despite having grown up in Brooklyn, and learned a very different set of place ethics than the one I know. I have one amazing neighbor, Anne, who feels to me like the neighbors who lived on my childhood street, Pamela Circle. I have two friends, Craig and Sarah, who live a couple streets over, who feel like home. But the scale on which this ethic operated in West Virginia—I just can’t seem to find it after leaving, no matter how hard I’ve tried.

I experience a double loss each fall, missing both the mountains of my childhood and the many mothers who played a role in raising me there.

—page 25, “Nine Forms of the Goddess”

LITTELL: Has writing these essays helped you assuage the “double loss” you mention in the quote above—or does your writing only intensify those feelings? Do you think you’ll continue to write about West Virginia?

AVASHIA: One really lovely outcome of writing this collection has been the way in which it has connected me to whole new sets of Appalachian communities—writers and activists and readers who I had not met growing up there, but who are doing such important work in Appalachia now. I feel a kind of re-connection to place that is surprising, and also inspires a lot of reflection on my part. I was told growing up that leaving was the only way to “succeed.” I’ve now had the opportunity to meet so many Appalachian people who made the conscious decision to stay, or to return after leaving, and who are really working to expand the mainstream understanding of what Appalachia is, and who lives there. And in meeting them, it’s helped me to really better see where I fit into that narrative.

I can’t imagine a kind of writing where Appalachia doesn’t inform my work in some form or another, just because Appalachia informs so much of who I am. Will it always remain at the center? Not necessarily. But will it always be in the frame, or just beyond the edges? I think so.

Margo Orlando Littell, Interviews Editor