What Is a Sketch but a Chalk

Outline Done in Pencil or Words?

An Interview with Nafissa Thompson-Spires

by Karin Cecile Davidson

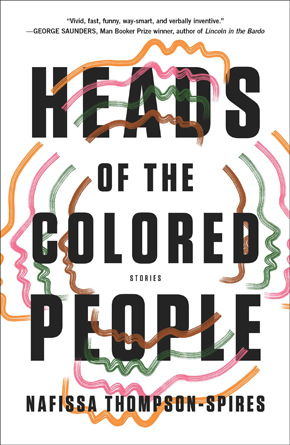

Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s debut story collection, “Heads of the Colored People,” selected for the 2018 National Book Awards Longlist for Fiction, strides into the worlds of black women and men, black girls and boys, upending stereotypes and straining against the limits of the expected through a dark, provocative humor. With a Ph.D. in English from Vanderbilt and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Illinois, and as a Callaloo fellow, Tin House alum, and Sewanee scholar, Thompson-Spires infuses her writing with scholarly works, 90s pop culture, and contemporary concerns. Black culture and identity in conversation with the tensions and politics of race are angled in ways that refuse definition. Through the unique cast of characters in twelve exquisitely startling, hilarious, and at times poignant stories, questions are asked about connection, collaboration, assimilation, resistance, and vulnerability. The collection’s title originates from 19th century James McCune Smith’s series of sketches, “The Heads of the Colored People, Done with a Whitewash Brush,” and the stories expand on this concept of sketches, incorporating the thematic treatment of “Heads,” wherein the characters are headstrong, headless, hotheaded, narcissistic, and even sustain head injury. Thompson-Spires constructs her worlds by way of a storytelling tightrope, demanding precision and balance, and sometimes departs the rope to walk beneath or fly above, revealing unforeseen topographies, rare and sloped and newly charted.

Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s debut story collection, “Heads of the Colored People,” selected for the 2018 National Book Awards Longlist for Fiction, strides into the worlds of black women and men, black girls and boys, upending stereotypes and straining against the limits of the expected through a dark, provocative humor. With a Ph.D. in English from Vanderbilt and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Illinois, and as a Callaloo fellow, Tin House alum, and Sewanee scholar, Thompson-Spires infuses her writing with scholarly works, 90s pop culture, and contemporary concerns. Black culture and identity in conversation with the tensions and politics of race are angled in ways that refuse definition. Through the unique cast of characters in twelve exquisitely startling, hilarious, and at times poignant stories, questions are asked about connection, collaboration, assimilation, resistance, and vulnerability. The collection’s title originates from 19th century James McCune Smith’s series of sketches, “The Heads of the Colored People, Done with a Whitewash Brush,” and the stories expand on this concept of sketches, incorporating the thematic treatment of “Heads,” wherein the characters are headstrong, headless, hotheaded, narcissistic, and even sustain head injury. Thompson-Spires constructs her worlds by way of a storytelling tightrope, demanding precision and balance, and sometimes departs the rope to walk beneath or fly above, revealing unforeseen topographies, rare and sloped and newly charted.

▱

And you should fill in for yourself the details of that shooting as long as the constants (unarmed men, excessive force, another dead body, another dead body) are included in those details. Hum a few bars of “Say My Name,” but in third person plural if that does something for you.

—Nafissa Thompson-Spires, “Heads of the Colored People: Four Fancy Sketches, Two Chalk Outlines, and No Apology”

DAVIDSON: In the title story, “Heads of the Colored People: Four Fancy Sketches, Two Chalk Outlines, and No Apology,” design and intention interact beautifully with the twisting storylines and crisscrossing characters, the play of language, and the endgame of misunderstanding turned to violence. At the forefront is the question of the whitewashed blackness of Riley: “Riley wore blue contact lenses and bleached his hair—which he worked with gel and a blow-dryer and a flatiron some mornings into Sonic the Hedgehog spikes so stiff you could prick your finger on them, and sometimes into a wispy side-swooped bob with long bangs—and he was black.” There is so much brilliant work accomplished here, directly and indirectly, calling up questions about race and role-playing, superheroes and police brutality.

How did you discover Riley and the other characters in this piece, especially in terms of how race is pushed and pulled in new and complex ways?

THOMPSON-SPIRES: That first line of the story kept coming to my mind, and when that happens, I often feel compelled to start writing. I followed the narrator’s voice—a voice I wanted to explore and just play with—until the characters became apparent. I didn’t know who this Riley was, but I followed him, so to speak, letting my imagination fill in the rest of the details. Then I started researching cosplay and anime, particularly black people who are invested in these lifestyles, to round out my characterization. Many others have written nonfiction about the racism involved in anime and roleplaying, and it’s hard to escape stories about police brutality. The story came to me from when I combined both issues.

He was not self-hating; he was even listening to Drake—though you could make it Fetty Wap if his appreciation for trap music changes something for you, because all that’s relevant here is that he wasn’t against the music of “his people” or anything like that.

—Nafissa Thompson-Spires, “Heads of the Colored People: Four Fancy Sketches, Two Chalk Outlines, and No Apology”

DAVIDSON: Musical references thread through several stories, from punk to R&B and rap and reggae to funeral hymns. Riley listens to Drake; Fatima thinks in strains more like those of Australian grunge band, Silverchair, than Rick James; Alma sings “Since I Laid My Burdens Down.”

If you set your stories to music, what would the playlist look like?

THOMPSON-SPIRES: I think, like the collection, the playlist would involve a delicate balance between levity and darkness. I’d include a lot of melancholy ’80s new wave and some ’90s grunge, along with some bright pop and hip-hop tracks. Fatima’s list of artists in “Fatima the Biloquist” actually might work as a representative playlist for the entire collection.

In the nineties you could be whatever you wanted—someone said that on the news—and by 1998 Fatima felt ready to become black, full black, baa baa black sheep black, black like the elbows and knees on praying black folk, if only someone would teach her.

—Nafissa Thompson-Spires, “Fatima, the Biloquist: A Transformation Story”

DAVIDSON: Several stories in “Heads of the Colored People” are linked via characters and strands of droll and dark humor, including “Belles Lettres,” “The Body’s Defenses Against Itself,” “Fatima, the Biloquist: A Transformation Story,” and “Suicide, Watch.” Fatima and Christinia are brought forward in these stories in ways that skirt togetherness: through others’ correspondence, in remembered events, by transformation attempts, and simply as a mention. Their rivaling mothers send each other letters by way of their daughters’ schoolbags. Fatima’s lifetime of overwhelming emotional and physiological struggles are set to the rhythms of a yoga class. During adolescence, Fatima examines her existence as “a sort of colorless gas… leaving the residue of something familiar…” and strives to change herself. And Jilly considers how to post a suicide note on Facebook, considering her life’s lack of backstory.

Would you speak about identity and the need for connection in these pieces, and how the fascinating and complicated Fatima appears in the collection multiple times?

THOMPSON-SPIRES: Identity is everything, or, at least, it can be. People who derisively speak of “identity politics” seek to deny the very real ways that race, class, gender, and other social constructs affect people’s everyday lived lives. I wanted to expose and probe the stakes of these constructs and their intersections head on. Fatima works well to anchor the collection’s concerns because we see her at multiple points in her life and in contemporary history. This is a character who lives through Reaganomics, the rise of yuppies and buppies, and later a first black President of the United States. She allowed me to explore a host of issues that affect the sort of post-soul generation, kids growing up after the major Civil Rights Movement, but still dealing with complex—and sometimes subtle, but sometimes not, as we see with Riley and state-sanctioned violence—racism.

DAVIDSON: Inside the collection are characters calling for help, whether in a Facebook post or through an ASMR video. Questions of identity and self-worth cross those of narcissism and social media. Specifically, these territories are tested in the portrayals of Jilly in “Suicide, Watch” and Raina in “Whisper to a Scream.” Jilly, surrounded by her Kawaii décor and updated online statuses, in the midst of sending out poetic suicide posts, reconsiders the possibilities of living. Raina, “who worked best in short frames, quiet slivers, fragments,” wants desperately to be seen as she really is—“I want to stop being afraid to tell the truth”—but feels the impossibility of moving in this direction.

DAVIDSON: Inside the collection are characters calling for help, whether in a Facebook post or through an ASMR video. Questions of identity and self-worth cross those of narcissism and social media. Specifically, these territories are tested in the portrayals of Jilly in “Suicide, Watch” and Raina in “Whisper to a Scream.” Jilly, surrounded by her Kawaii décor and updated online statuses, in the midst of sending out poetic suicide posts, reconsiders the possibilities of living. Raina, “who worked best in short frames, quiet slivers, fragments,” wants desperately to be seen as she really is—“I want to stop being afraid to tell the truth”—but feels the impossibility of moving in this direction.

What might you tell us about the headspaces of these characters?

THOMPSON-SPIRES: They are all dealing, in some way, with the burdens of both their privilege (as middle-class black people with access or proximity to the privileges of whiteness) and the realization that privilege doesn’t necessarily guarantee happiness. Each of these characters feels unseen, invisible in the traditional racial sense as outlined by Ralph Ellison, but also invisible as people beyond race, reduced to their bodies or their superficial descriptors.

Alma kept her eyes shut as she sang inside the church and later at the burial site. There was something about a closed casket that made her anxious, left too many gaps for her imagination to fill in. She tried to focus on her song. Thirteen. The boy was the same age as the number of bullet holes in his body, from head to torso.

—Nafissa Thompson-Spires, “Wash Clean the Bones”

DAVIDSON: Burdened with her own physical pain, anxieties, and sleep deprivation, Alma suffers with overwhelming concern for a baby son who will grow up in a world that destroys black bodies.

What are the origins of Alma, her voice, her work, and her grueling challenges?

THOMPSON-SPIRES: I wanted to challenge myself to tell a serious story without humor as a crutch. I’d seen an article about a funeral singer (which I didn’t actually read, lest I borrow too much from it), and I was intrigued by the idea of someone who spends their life trying to heal others and what her private pain might look like. The pain of mothering—while surrounded by other people’s trauma—stood out to me.

How to end such a story, especially one that is this angry, like a big black fist? … I concede that it might have been so much more readable as a gentle network narrative, with the cupcakes and the superheroes and the blue eyes and the nineties image-patterning. But I couldn’t draw the bodies while the heads talked over me, and the mosaic formed in blood, and what is a sketch but a chalk outline done in pencil or words?

—Nafissa Thompson-Spires, “Heads of the Colored People: Four Fancy Sketches, Two Chalk Outlines, and No Apology”

DAVIDSON: The architecture of the collection as a whole and in each individual story is created in part through the constructs of language: how a meta-narrator may speak directly to the reader; how characters must carefully navigate their worlds in order to be seen and recognized and not shot down, figuratively and literally; how satirical wordplay illuminates story, raising the stakes for characters and awareness for readers.

Who are the writers who inspire and call you to push literary boundaries? Are you reading anything now that is sending you in new directions?

THOMPSON-SPIRES: As for what I’m reading now, I really loved Danzy Senna’s “New People,” and it made me want to return to her short fiction (some of which I’ve taught before). And Yrsa Daley-Ward’s memoir, “The Terrible,” is lovely and has revived my interests in reading literary nonfiction. I’m a big fan of the so-called “Post-Soul” black writers: Percival Everett, Mat Johnson, for instance, especially their approaches to satire and contemporary black experiences—and the plurality of those experiences. And I’ve been heavily influenced by Ishmael Reed’s play with form, emphasis on play. I think writing should involve experimentation and play, not just prescribed axioms.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor