What Becomes Beautiful is the

Wildest Thing: An Interview with

Molly McCully Brown

by Karin Cecile Davidson

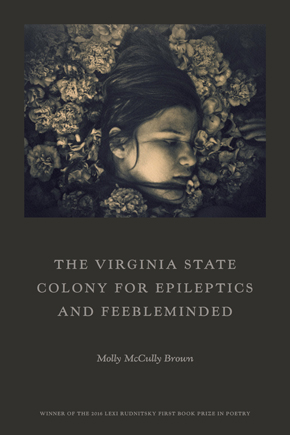

Molly McCully Brown’s poetry collection, “The Virginia State Colony For Epileptics and Feebleminded” (Persea Books, 2017), winner of the 2016 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize, summons historical shadows along with bright beams of empathy and identity. Exploring the lives of those who were institutionalized within and employed by the Colony from Fall 1935 to Fall 1936, Brown’s poems lead us from dormitory to solitary confinement—“the Blind Room”—out into the field, the chapel, the infirmary, and back into the dormitory. The progression through physical spaces—spare, confined, and horrific—reaches beyond the Depression years, echoing back to 1910 when the “government-run residential hospital” first opened in Amherst County, Virginia and forward to its transformation to the Central Virginia State Training Center. In these pages, it becomes clear that internment was not the only plight for those within the Colony, for passages reveal the practice of Eugenics, wherein patients regarded as “defectives” underwent sterilization. Attentive to the individual bound with physical and mental difference, the collection calls up the cries and scarce laughter, the whimpering and swearing and silence of the bodies within its walls.

Molly McCully Brown’s poetry collection, “The Virginia State Colony For Epileptics and Feebleminded” (Persea Books, 2017), winner of the 2016 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize, summons historical shadows along with bright beams of empathy and identity. Exploring the lives of those who were institutionalized within and employed by the Colony from Fall 1935 to Fall 1936, Brown’s poems lead us from dormitory to solitary confinement—“the Blind Room”—out into the field, the chapel, the infirmary, and back into the dormitory. The progression through physical spaces—spare, confined, and horrific—reaches beyond the Depression years, echoing back to 1910 when the “government-run residential hospital” first opened in Amherst County, Virginia and forward to its transformation to the Central Virginia State Training Center. In these pages, it becomes clear that internment was not the only plight for those within the Colony, for passages reveal the practice of Eugenics, wherein patients regarded as “defectives” underwent sterilization. Attentive to the individual bound with physical and mental difference, the collection calls up the cries and scarce laughter, the whimpering and swearing and silence of the bodies within its walls.

Brown’s poems reside within these walls, taking on the voices of women and girls trapped and suffering, wishing a way out, into the seasons, the heat and thunderstorms, the fallen leaves and wind, the ice and eventual budding blossoms. Constrained inside the heavy slip of “standard-issue Virginia cotton,” once dressed in calico and lace; desirous of a body that might run through fields, “pick strawberries and coax milk from cows,” but too bent and twisted for such physicality; undone by an “accident of nature,” or perhaps by the passage of time inside, so that all a mind can fathom is nothing at all, or an illusion of what once was. The collection possesses much beauty, and as much compassion, for the language cradles the narrative gently, never accepting its fate, successful in its understanding of crimes committed, of lives once unacknowledged, finally acknowledged here.

Whatever it is—

home or hospital,

graveyard or asylum,

government facility or great

tract of land slowly ceding

itself back to dust—–Molly McCully Brown, “The Central Virginia Training Center”

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: “The Virginia State Colony For Epileptics and Feebleminded” is a stunning collection. Its breathtaking strength and connection, its calm and passion all rest beautifully in the realms of identity, understanding, and compassion. In the introductory poem, the narrator speaks of the proximity of the land and buildings of the Colony, and reveals her desire to learn of the lives there.

Was realizing the Colony’s history through poetry a choice that allowed you to delve more deeply than you might have in another form?

MOLLY MCCULLY BROWN: First of all, thank you so much for your kind words about the book. I love the idea that the collection is an act of connection, and also the idea that it’s possessed of both calm and passion, and somehow working to move inside those two extremes.

I don’t know that I think that approaching the Colony’s history through poetry allowed me to delve more “deeply” necessarily. I think the difference, though, is that unlike, say, a journalistic account of the history of Eugenics in Virginia, which would be obligated to adhere exclusively to verifiable fact, a collection of poems can take up those facts as a starting point and then make leaps of empathetic imagination to paint a more human and emotionally engaged picture of a time and place. I have in mind, here, Caroyln Forché’s notion of “poetry of witness”—that is, poetry that’s interested in serving as social and emotional record—and I love what she says in her essay “Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness:” “A poem that calls us from the other side of a situation of extremity cannot be judged by simplistic notions of ‘accuracy’ or ‘truth to life.’ It will have to be judged … by its consequences, not by our ability to verify its truth.”

Lay out on the pine floor:

rattle your own bones back

to the center of the world.–Molly McCully Brown, “Grand Mal Seizure”

DAVIDSON: “Grand Mal Seizure” is a poem I keep returning to. The first line pulls me in, gently and yet firmly, as if by the wrist: “There’s however it is you call, / & there’s whatever it is / you’re calling to.” Abandonment, institutionalization, violence received and violence committed to those weaker in return, and outside, the natural world of dogwood blossoms, wind, clay, cicadas, and the eventual arrival of yet another girl. At the end of this poem, one experiences an inversion of the beginning line, creating a re-visitation, a parenthetical moment spoken in second-person perspective, as if to the reader, as if to oneself. “There’s whatever it is / you’re calling to. There is / however it is you call.”

Tell us about poetic form—those tercets!—and that grounded, yet unearthly narrative voice.

BROWN: As you know, this is a form that reoccurs throughout the book: these long poems in tercets that are sometimes anchored to the left-hand margin, and sometimes italicized and indented into the middle white space of the page. I love that you describe the voice as both grounded and unearthly, because my hope is that, as the lines depart from and return to the margin that’s exactly the dichotomy they’re enacting: continually abandoning and then coming back to the physical world, the body, a knowable and narrate-able experience of being alive in the world.

To some extent, I intend the floating, italicized tercets to evoke the experience of seizure, so that—as in “Grand Mal Seizure”— the poems are enacting formally their narrative concerns, but even more than that, I wanted the form to make room for the simultaneous existence of what is explicable and what is not, what’s embodied, and what is spiritual, and what occurs in the space between the two. I wanted to allow room for both the literal and metaphorical, the quotidian and the extreme, and to try to locate the poems on the knife’s edge between suffering and some kind of ecstatic experience that can occur in the most unlikely of places and at the most unlikely of moments.

My hope is that the brief and compressed space of each tercet is always in tension with the poem’s impulse to yearn toward something bigger, wilder, outside of itself.

Imagine, you have never been to the ocean

but the ocean is in you,

& sometimes, it roars.–Molly McCully Brown, “New Knowledge for the Dark”

DAVIDSON: The natural world lies outside, and only the girls who work in the fields or hang out laundry experience the wind and sun, the gravel or grass under their feet. And then again, those contained within know this world exists, through the windows, in their memories, in the damaged interiors of their minds. Throughout the collection and in the “Where You Are” series, exterior and interior spaces are painted in precise, detailed strokes; we come to understand the beauty and misery of each place.

How did you find your way to this landscape, both the interior and exterior worlds? And what led you to the “Where You Are” poems?

BROWN: So, the physical world of the book—both the fact that it’s located centrally and explicitly in the rural Virginia landscape, and then that it’s further organized into the individual rooms and spaces of the Colony—has been a part of my conception of the manuscript since I first began to imagine it. This is due in large part, I think, to the fact that I grew up in the mountains of Virginia only a few miles from the grounds of the Colony and am intimately familiar with and attached to that part of that world. It’s also an artifact of the fact that the time I spent actually exploring the former Colony—which is still an operational residential facility for adults with serious disabilities—was incredibly formative for me.

BROWN: So, the physical world of the book—both the fact that it’s located centrally and explicitly in the rural Virginia landscape, and then that it’s further organized into the individual rooms and spaces of the Colony—has been a part of my conception of the manuscript since I first began to imagine it. This is due in large part, I think, to the fact that I grew up in the mountains of Virginia only a few miles from the grounds of the Colony and am intimately familiar with and attached to that part of that world. It’s also an artifact of the fact that the time I spent actually exploring the former Colony—which is still an operational residential facility for adults with serious disabilities—was incredibly formative for me.

Like a lot of places in Virginia, the Colony was built on an enormous amount of land. As the original buildings fell into disrepair, instead of either rehabbing them to bring them up to code, or demolishing them and constructing new buildings in their place, people simply moved out of the older buildings, left them standing, and built new structures on all the land around them. This renders the place a haunting combination of a functioning facility and a ghost town of everything that it was.

As I walked around the place, I kept thinking about what a small collection of buildings, in all this vast space, actually comprised the original Colony, and about what a physically circumscribed life Colony patients would have lived. The place felt both so evocative and so confined, and my hope is that the shape of the book reflects that.

The “Where You Are” poems that begin each section arose out of my desire to locate the reader in the physical and emotional space of the Colony in as profound and complete a way as possible: a way that mirrored my own deeply moving experience of the place. I was thinking, when I imagined them, about the little icons on public maps that allow travelers to locate themselves in unfamiliar territory—the tiny pins or symbols that announce: “you are here.”

everything is without history

there was never anyone but you in this cold lightless place–Molly McCully Brown, “The Blind Room: A Consecration”

DAVIDSON: Place, memory, language. Pattern, repetition, the series of “Where You Are” poems. And then, at the end of several pieces lie a trio of words—distance, water, sex; running, flying, faith; flock, flinging, frost; Father, Son, Holy Ghost—each followed by the description of a space, a moment, the girls, a maybe. And interesting, too, are the lines and stanzas heavy with space, in which the erratic, staccato, nearly breathless momentum creates a sense of unease. “The Blind Room: An Execration” and “The Blind Room: A Consecration” follow this form, appearing to mirror each other on adjoining pages, but in truth reaching beyond this toward inversion, abomination on one side, dedication and devotion on the other.

Tell us about your choice of pattern and form throughout the collection, your decisions about the overall architectural structure, with specific reference to the mirrored “Blind Room” poems.

BROWN: In response to the previous question, I talked a little bit about the structure of the book: the fact that each section is titled after a particular room or space in the Colony. Each section title includes, too, a season and a year, so that the book is moving temporally at the same time that it’s moving spatially.

Although the book doesn’t exactly have defined, distinguishable characters, I did want the reader to have a sense, as they moved through the sections, that certain voices were growing familiar, that they could begin to identify particular perspectives reoccurring as the book proceeded. My notion is that the forms you identified—the poems in alternating indented tercets, the poems ending in a trio of strange, indirect definitions, the poems riddled with space and caesura—serve as signposts to help guide you through the collection. You see one and think, “I’ve seen this before,” and then, as you read them, I hope you think, “I’ve looked through these eyes before; I know this vision, this voice.”

I wanted the diction of the book to be fairly direct and repetitive because, as I said before, I was struck by how small and circumscribed the space(s) of the Colony were, and I wanted the collection’s vocabulary to reflect that plainness and boundedness, that sense of immutable limit. On the other hand, though, I wanted to allow room to evidence the full and phenomenal space of the women’s psyches and imaginations, their joys and agonies, the whole and complete lives they had to play out in their heads behind Colony walls. The handful of poems like the ones you identify in the Blind Room—which at first appear to mirror each other and then diverge—provided the perfect vehicle for this because I could convey, simultaneously, a pervasive sense of confinement and repetition and also a psyche beginning to burst the bounds of a terrible experience so that it could be considered and experienced—even in the darkness—in an entirely different light.

I will remember this day as the day

I was cleaved from my body.

Whatever they did, I amthe silt that slips between your fingers

when you dredge for the bright things

at the bottom of a pond.–Molly McCully Brown, “The Cleaving”

DAVIDSON: “In the Infirmary (Summer 1936)” sends us into the territory of Eugenics. Inside “the loveliest building in the colony … the year Scarlet O’Hara falls in love with Tara … some fifteen hundred people are cut open and wrecked.” The poem, “A Dictionary of Hereditary Defects—the comparison of idiots and normal children must almost be a comparison between two separate species,” delivers the afflictions whereby one is chosen for sterilization, along with the reasoning—emotionally disconnected, medical—that it is a far, far better thing to “drown the smallest kitten” than to have more “feeble and stunted” creatures come into the world.

Between these poems are a fictional State Hospital Board’s orders, each for a discrete “inmate” of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, providing a list that can be checked off—insane, idiotic, imbecile, feebleminded, epileptic. These maladies are offered up as reasons by which the medical authorities have the right to sterilize, as “the laws of heredity” point to “socially inadequate offspring likewise afflicted.” There’s brilliance here, derived of truth, made by personalizing the moment, creating a character—a woman with a name—for each impersonal, government-issued document. Miller, Edith – May 9th 1936. Campbell, Dorothy – July 24th 1936. Carr, Frances – August 24th 1936.

Research, reams of archival documents, notes on the American Eugenics Movement—the work must have been extensive. Would you describe the process of learning and recognizing what you needed to know about the historical background of the Colony and the Eugenics movement? And are there writers and poets whose work influenced your decisions about this collection?

BROWN: Thank you for such a wonderful description of how research and documentation are working in the “Infirmary” section.

The process of doing research for the collection was at once harrowing and fascinating. As I said before, maybe the most formative research I did was to actually spend time walking around the Colony’s grounds: through its cemetery, along its roads, and inside its abandoned buildings. That experience gave me the shape and structure of the book, and in many ways, I think, its heart.

I also spent time with the limited official records from the Colony that are available through the Library of Virginia, and even more with the “Image Archive on the American Eugenics Movement,” which is an online database maintained by the Dolan DNA Learning Center at Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory. It includes everything from newspaper articles about Eugenics written in the ’30s and ’40s, to relevant legal documents, to photographs and propaganda postcards of “defectives” distributed to advance the agenda of eugenicists, to medical documents and that provided a model for the invented sterilization orders you refer to above.

In addition, I owe a lot to the work of a few Virginia journalists who, in the ’80s and ’90s, spent a good deal of time researching and writing about the aftermath of the Eugenics movement in Virginia, and in some cases even speaking with former Colony patients about their experiences. Otherwise, patient accounts are very few and far between.

All this to say: I learned a lot that didn’t explicitly make its way into the collection. But I wanted to be as informed about the history and framework of the Eugenics Movement as I could reasonably manage without drowning in research and minutiae. As painful as it was, I also wanted to be utterly immersed in the language and attitudes of the time, so that, even if I wasn’t drawing directly or consciously on that historical information, it could provide a kind of underpinning for every choice and gesture I made in the book.

I’m indebted to a number of poets for providing me with wonderful models of collections that grapple—in a variety of ways and combinations—with how to manage history, invented biography, and research in verse: A.Van Jordan, Natasha Trethewey, Gabrielle Calvocoressi, and Tyehimba Jess are just a few.

Lord, most of what I love mistakes itself for nothing.

–Molly McCully Brown, “Transubstantiation”

DAVIDSON: There is so much to love about this collection. One can be brought to her knees by the terrifying, merciless actions that occur within the Colony; the radiance of the surrounding land, the sweep of seasons; the hopelessness and desperation. And then there is the kindness and great expressive heart of “Interlude,” a section in which transubstantiation, the memory of love, the recognition of connection and identity fly forward. Here, one is bathed in language, story, and possibility.

Tell us about “Interlude.”

BROWN: Originally, the “Interlude” section was just comprised of a single poem—“Going to Water”—and I envisioned it as a chance for the reader to get a little breathing room from the immediate space of the Colony and have a brief, dream-like window into the life of one of the Colony patients before she was institutionalized. My brilliant editor, Gabriel Fried, saw that the section had more potential and encouraged me to imagine that space as one that might provide an opportunity for my own life to come into communion with the Colony, its patients, and its history. “Transubstantiation” and “To That Girl, as an Infant” attempt to do that work a little, as well as to provide a kind of intermission for the reader, and a sense of the possibility of a world beyond Colony walls.

What becomes beautiful is the wildest thing

You are made from all that and a thicket

of thistle, a boat full of cardamom pods,

a room in a house in Virginia

Beloved, you are held in every

improbable thing I’ve ever done.–Molly McCully Brown, “To That Girl, As an Infant”

DAVIDSON: I understand that you are working on “a collection of essays about disability, poetry, religion, and the American South that explores the relationship between the body and that intangible other we sometimes call the soul.” Poetry is a medium in which your understanding of language is layered with depth and meaning and intense beauty. This strength is also found in your essays, and I’m thinking, here especially, of “Bent Body, Lamb” (Image Journal, Issue 88), in which you describe your experiences of finding faith and, ultimately, a way back to your twin sister, Frances, to whom, along with your parents, your poetry collection is dedicated. “This sense of another body—in yours—or barely beyond yours—or instead of yours—marks your life like a lighthouse lamp, waning and flaring in the distance.” One can sense this dedication throughout the collection, the burden and the love, in lines and even within entire pieces, such as “To That Girl, As an Infant.”

Would you describe the difference of experience in composing a poem versus channeling words into essay form, when the narrative in both events is deeply identified and recognized?

BROWN: The First Line of John Donne’s fifth Holy Sonnet is, “I am a little world made cunningly,” which has always struck me as the greatest description for a poem: this little, cunning, compressed world that is utterly its own ecosystem, that writes its own rules, and teaches you its own shape, its own language and logic. To write a poem, for me, is always most fundamentally an act of world “making.”

To write an essay, on the other hand, is for me more an act of world “exploring” or “reckoning,” in which I have a little more space to consider and investigate the world as it “is” going on around me: to provide context, make digressions, tell stories in a less oblique way. Poetry will always, I think, feel like my first language, but I’ve found that essays push me toward a different kind of discovery. And I’m grateful to be able to read and to write in both forms.

The truth is that I’m drawn—both as a reader and a writer—to the same things in poems and in essays: to surprise, to strangeness, to the simultaneous existence of joy and grief, to detailed and inventive descriptions of the body and detailed and inventive descriptions of the mind, to lyricism and belief in beauty and a steely-eyed refusal to look away from what is most difficult.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor