The Umbilical Pull of Place:

An Interview with Megan Culhane Galbraith

by Margo Orlando Littell

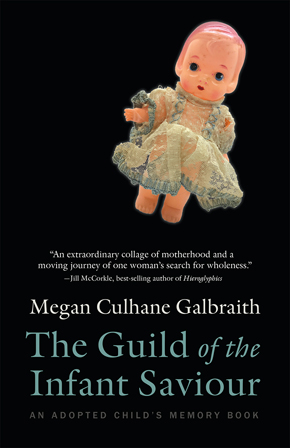

Imagining unknown worlds is the wonder and purpose of play—and in her memoir The Guild of the Infant Saviour, Megan Culhane Galbraith shows that the world of an adoptee is often a blank landscape just waiting to be conjured. Using text, photographs, and recreations of those photographs in dollhouse scenes, Galbraith examines questions of her birth and childhood, which unspooled against the cultural backdrop of adoption and motherhood in the 1960s. Full of courage, pain, anger, and an open-hearted desire for self-discovery, The Guild of the Infant Saviour goes far beyond personal history, examining questions of identity that are often shrouded in secrecy and shame. Galbraith talks with Margo Orlando Littell about her hybrid work, the dolls that inspired her art, and the dystopian elements of adoption and the life of adoptees.

Imagining unknown worlds is the wonder and purpose of play—and in her memoir The Guild of the Infant Saviour, Megan Culhane Galbraith shows that the world of an adoptee is often a blank landscape just waiting to be conjured. Using text, photographs, and recreations of those photographs in dollhouse scenes, Galbraith examines questions of her birth and childhood, which unspooled against the cultural backdrop of adoption and motherhood in the 1960s. Full of courage, pain, anger, and an open-hearted desire for self-discovery, The Guild of the Infant Saviour goes far beyond personal history, examining questions of identity that are often shrouded in secrecy and shame. Galbraith talks with Margo Orlando Littell about her hybrid work, the dolls that inspired her art, and the dystopian elements of adoption and the life of adoptees.

I realize now that I don’t need to apologize for my existence.

—Megan Culhane Galbraith, page 3

MARGO ORLANDO LITTELL: Play, usually thought of as the realm of children, takes on weighty, even sinister significance as it unlocks new sides of old memories, unexamined/unacknowledged feelings, and questions about your past. Of course, writing—especially memoir writing—is another way of making sense of the past. Megan, how did you come to pair your play-based visual art with written memoir? In a way, the art-making is a kind of research for a larger work, while also being a fully fleshed-out work on its own.

MEGAN CULHANE GALBRAITH: Margo, you are so right about art making as research, and play unlocking new sides of old memories. I love being able to express myself in multiple forms that feel unconstrained and unclassifiable. What comes to me on the page has usually begun in the dollhouse, or in a collage, or by literally drawing something out in my sketchbook.

I came to visual art quite by accident. Around the time I was finishing the first iteration of my manuscript for my MFA at the Bennington Writing Seminars, I found the dollhouse and shortly thereafter, the dolls. One day during our residency I crammed my friends in my car to explore a local antiques mall. As I rounded a corner I saw this dollhouse on a top shelf like a beacon. I had to have it. I went on a few binges buying the cheap plastic furniture and then I just started playing with it.

I’d taken my dollhouse to the first artist’s residency at The Saltonstall Foundation in Ithaca, NY. It was a security blanket in a way. I brought it with the idea that if I got frustrated with my writing I’d at least have something to play with. I hadn’t yet thought about pairing images with my essays. It was in Ithaca that I discovered the DOMECON practice babies and began restaging the archival photos in my dollhouse—again, as a way of playing at something I couldn’t yet understand. Years later, I’d submit those images to a call for art at Collarworks Gallery in Troy, NY, where I live now. The curator of the show was Alexandra Foradas, the curator for visual art at MASS MoCA. I didn’t know much about the “art world” at the time so it felt weird to me to submit these black-and-white images printed on a basic printer and stitched together with thread from a cast-off sewing kit I’d found in the drawer of my studio. I was stunned and excited when Alexandra accepted my work. She was so kind helping me choose which pieces to hang in the show, and that artwork became the basis for “Hold Me Like a Baby,” the essay that is the spine of my book. Thanks to that essay, I had an epiphany. I realized the format I was seeking for my book was there in front of my eyes the entire time thanks to those babies.

I’d taken my dollhouse to the first artist’s residency at The Saltonstall Foundation in Ithaca, NY. It was a security blanket in a way. I brought it with the idea that if I got frustrated with my writing I’d at least have something to play with. I hadn’t yet thought about pairing images with my essays. It was in Ithaca that I discovered the DOMECON practice babies and began restaging the archival photos in my dollhouse—again, as a way of playing at something I couldn’t yet understand. Years later, I’d submit those images to a call for art at Collarworks Gallery in Troy, NY, where I live now. The curator of the show was Alexandra Foradas, the curator for visual art at MASS MoCA. I didn’t know much about the “art world” at the time so it felt weird to me to submit these black-and-white images printed on a basic printer and stitched together with thread from a cast-off sewing kit I’d found in the drawer of my studio. I was stunned and excited when Alexandra accepted my work. She was so kind helping me choose which pieces to hang in the show, and that artwork became the basis for “Hold Me Like a Baby,” the essay that is the spine of my book. Thanks to that essay, I had an epiphany. I realized the format I was seeking for my book was there in front of my eyes the entire time thanks to those babies.

As children, we play to control our world. As adults, we learn we have no control over our world, and perhaps I returned to play when I rediscovered my inner child. Perhaps I needed to return to a state of being pre-verbal, clutching my dolls and my comfort objects, in order to understand how to verbalize the feelings I’d been numb to as a child.

I had three mothers before I was six months old: my birth mother, my foster mother, and my adoptive mother.

—Megan Galbraith, page 74

LITTELL: The scenes from The Dollhouse and your childhood photographs connect play to reality in a way that is uncomfortably explicit. The twinned images tilt our established assumptions about foundational ideas—adulthood, childhood, the purpose of play. Your memoir makes clear the effect that the recreated scenes have on your self-examination and identity; but can you speak to the effect you intended/expected these images to have on outsiders? Looking at the scenes as a reader feels doubly voyeuristic—your “angle of removal” from the situation, compounded by readers’ own remove.

GALBRAITH:

Using image to tell a story sure gives the needed distance I felt was necessary. Recreating my baby book images in the dollhouse allowed me to connect with myself in a much different way. I struggled early on as a writer with using the passive tense and I realize it was directly related to the struggle to use my voice.

My intent with pairing image and essay is to create a complementary through-line to the narrative. Like melody and harmony. Parents document the life of their children in photos, and my photographs evoke the Polaroids my mother or grandmother might take. They’re a bit askew, and a little blurry; if you look closely at the one of me on the giant green foot nap mat you’ll see my dog’s nose poking in from the right side. There is a sense of allegory and fairy tale I adore; a third person “you” in complement with the first-person “I” of the words.

It’s hard to write a book; especially memoir/essays while thinking about how a reader might interpret it or what affect it will have on them (family members’ reactions have been full of projection). I had to divorce myself from thinking about that and remind myself the only thing I have control over is my intent, my honesty, and the vulnerability I put on the page.

I’ve always been fascinated by how children’s books combine pictures or illustration with words. There’s an innocence and power to children’s books, and if you read them with adult eyes there is an enormous seriousness to the subjects they tackle. I wanted my book to evoke that tension between innocence and power.

In the same vein of the DOMECON baby images, I decided to put my original baby photos at the end of each essay for circularity of the through-line: a created scenario that fronts the essay and an original artifact that ends it. I feel it grounds the narrative in two worlds––play and reality––and heightens the dystopian nature of adoption.

Most of my dolls are creepy. Some damaged. Maybe this is the point.

—Megan Culhane Galbraith, page 244

LITTELL: Creepy dolls—or dolls that adults view as “creepy”—are common in children’s literature, and you draw attention to a beloved book from your childhood, The Lonely Doll. Old dolls in particular seem “creepy”—staring from the windows of thrift stores or ebay listings. But when given new purpose, such as in your dollhouse scenes, they take on a different kind of affect, less creepy than meaningful, tender, and peaceful. I wonder how closely linked a doll’s “creepiness” or grotesqueness is to the fact of its abandonment—could its status as an unwanted thing be part of what we perceive as “creepy”? And, if so, is “creepy” just a more palatable way of processing the heartbreak of a beloved childhood doll being left behind? Talk to us about your doll collection, and how your view of the dolls has changed as they’ve inhabited your art.

GALBRAITH: There’s a loneliness to all dolls with their vacant stares, broken limbs, and frozen smiles, isn’t there? All found objects come with a history but its up to the finder to make up the story because a doll can’t speak. In a way that’s what I’ve done with my adoption. I’ve listened to stories about my childhood, heard tales from my birth mother, looked endlessly into photos of myself as a child trying to figure out what I was thinking, and filled in missing pieces of my story with research. When I pick up a doll or one of the fragile little babies in a thrift or antique store, I’m also thinking about how they came to be there. Did relatives find them in an old trunk and needed to get them out of the house? Had they been owned and loved by a child? Were they given as gendered objects of what it means to be female?

I play with the ideas of motherhood, identity, and gendered versions of sexuality in my book using the dolls as foils. They are vintage Sixties-era dolls in keeping with a time when women were constricted by clothing, society, and gender roles. I like to play with that constriction. It’s something to push against.

My dolls have agency because I’ve given them agency by subverting the dominant paradigm. In my art in The Dollhouse they aren’t passive victims but, rather, assured and powerful. I recently did a visual fairy tale where I turned the Cinderella trope on its head. I feel I’ve liberated these dolls from a boring and frozen existence.

Again, this goes back to me being pre-verbal as a baby and having no control. In many ways, adoptees are treated as found objects that are expected to take on the conditioning and heritage of their adoptive parents and families and be happy about that.

The Lonely Doll is such a striking book, isn’t it? I feel that Dare Wright, the author, liberated herself through her doll Edith. She gave Edith a life and friends and agency even as she felt lonely and desperate for the same in real life with an absent mother. Reading that book over and over as a child, I felt her loneliness before ever knowing her story.

These places haunt my dreams. There has been no sense of closing the circle, or of finding answers. These places are pieces of my history that have vanished, leaving nothing but a vapor trail.

—Megan Culhane Galbraith, pages 40-41

LITTELL: So much of your story is rooted in feelings of trespass—of approaching and exploring spaces where you are not meant to be. The hospital where you were born, the house where your birth mother, Ursula, grew up. Particularly striking is your visit to the site of the Guild of the Infant Saviour, the unwed mothers’ home where your birth mother lived while pregnant. The building is nothing like what it once was; there is no visual evidence of its history. You and Ursula were together in this same spot decades ago, but the memory is only Ursula’s. How did writing your memoir contribute to the process of claiming your own history in these places?

GALBRAITH: Place has an umbilical pull for me. I go to an actual place that’s significant to me and am transported back in time. I try to feel in my body the events that occurred there. When I stood outside what used to be the Guild and realized I hadn’t gotten there in time to see the original brownstone, I felt a heaviness in my chest, like I’d lost a piece of me. I really really would have liked to have been able to go inside and stand in the foyer or where the reception desk might have been. Same with the hospital where I was born; I had a burning desire to squeeze through the chained doors and find the maternity ward to stand there and feel something.

I write and play to understand myself better and to puzzle out my feelings. It’s the same with traveling to these places. I want to feel my history and to do that means being embodied in those places and then listening hard to how my body is feeling while I’m there. I remember feeling enormous sadness; a heaviness in my chest. It felt like an erasure: the plastering over of a secret.

I was playing with the concepts of home and family. My baby dolls were objects of play, but the Domecon babies were real experiments: human objects. Recreating their photographs in the dollhouse made the practice of practice babies seem dystopian.

—Megan Culhane Galbraith, pages 71-72

LITTELL: The Domecon babies—orphans cared for by young women in Cornell’s Domestic Economics program in the first half of the 1900s—serve as a startling allegory for how you felt/feel as an adoptee. They reflect your feelings of fragmented early childhood, along with your lingering insecurity and fear of abandonment—and they force us to examine our assumptions about the mother/child bond, the “role” of a baby, and the obligations attendant to motherhood. The Domecon babies receive care but not devotion. Though you point out that “most grew up with no knowledge of […] having been a Domecon baby,” it’s impossible to believe there was no lasting impact. How did your discovery of the Domecon program affect your quest for self-knowledge, and how did it shape your writing of this work?

GALBRAITH: Those babies offered me a lens through which I could see the effect adoption had on me. I owe those babies so much. Finding the images of the Domecon babies and restaging them in my dollhouse gave me the idea for the structure of the entire book. It came to me late in the throes of editing, before I began submitting the book.

My friend Walter read a draft and suggested I structure the book like a baby book. As I re-read the essay “Hold Me Like a Baby,” I realized the answer was right in front of my eyes. I could restage my baby photos in the same way I did the Domecon babies and evoke the idea of a baby book. I woke up one morning and began sketching tidbits from the items in my Adopted Child’s Baby Book. Sketching loosens my hand and my mind and allowed me to see things I hadn’t before in my baby book. I used those sketches in the collage that is the frontispiece of the book. Isn’t it interesting that what I needed had been right in front of my eyes all along? It shows the vast difference between “looking” and “seeing.”

I’d thought a simple number would unlock all the clues, like a codex, or the keys to a safe deposit box full of family secrets: as if this library full of information owed me something. As if by possessing this tiny data point, I could access my entire biological life story that would rush into my brain and make me feel whole, and right, and real.

—Megan Culhane Galbraith, pages 52-53

LITTELL: Your adoption history plays out in 1960s New York City, a time when homes like the Guild weren’t uncommon and experiences like Ursula’s weren’t unique. Your research is done on the ground, with paper records and in-person visits to significant locales. While your memoir is a deeply personal, wrenchingly intimate story, it is also a kind of snapshot of a particular time and place. How did sinking into this time and place impact your writing and your art? And has New York changed for you, post-publication? Many city-dwellers, current and former, feel ghosts on every corner; your relationship with the city seems, perhaps, especially complex.

GALBRAITH: Ghosts on every corner indeed. Sinking into a time and place allows me to bathe in the past. I feel transported by the ghosts of that time. I imagine what the place looked like and how it’s changed or hasn’t over time. It’s been interesting to chart the path my birth mother walked based on her stories. From the Guild, to the bodega on the corner, to the Central Park Zoo. I mapped a cab ride from the Guild to St. Clare’s, thinking about Ursula on her way to give birth. The street patterns don’t change in NYC. Those grids are arteries. I wonder if Catholic Charities planned the location of the Guild to be a straight line from the East 50s to the West 50s to the charity hospital. In DUMBO also, it’s easy to transport myself back in time because the cobblestone streets and buildings remain unchanged. Sometimes I imagine hearing horses and carriages.

When I was in high school I’d skip school and take the train into NYC with my girlfriends. I’d wanted to find Carnegie Hall because I played the violin, so we were in the West 50s. I remember standing on a street corner waiting to cross when I had the visceral memory of being in that exact neighborhood before. I froze. I felt the world slow down. I dissociated. It felt like I was looking through a pinhole camera. I remember searching the faces of the women walking by for resemblance; wondering if one of them could be my birth mother.

I remember my friends tugging at me to cross the street so I returned to my body. I only put it together decades later that we were in the neighborhood where I was born. Hell’s Kitchen was three blocks away and St. Clare’s hospital was a five-minute walk.

This July I was in NYC showing a high school friend the DUMBO neighborhood. We were on the Brooklyn Bridge and I wanted him to see the clock tower, but I got disoriented and couldn’t find it on the horizon at night. I could see the giant digital clock that flashes red over The Watchtower building, but I couldn’t locate what I call the “terrestrial moon” in my book. I felt a mild panic as I searched the night sky for those clock faces. It was as if I’d dreamed my whole tenuous existence. Then my friend grabbed my hand and grounded me back to reality.

It’s incredible how memories live in our bodies; how they’re activated by place, smell, touch, and taste. I’m learning to pay acute attention to my body and how it feels these days.

I was an adopted person who didn’t know her ancestry. I was a person who didn’t know her people. I felt suddenly irresponsible for bringing a child into the world without knowing my heritage. I worried that all the stories and family lore I’d be passing along were adjacent ones, not biological, not the truth—like these narratives were mine, yet not mine. It was as if I were two people and had parallel life somewhere else.

—Megan Culhane Galbraith, page 23

LITTELL: One of the striking things about your memoir is the visceral feeling of displacement on the page—this isn’t simply a recounting of a journey; it’s an almost real-time experience of a writer’s attempt to understand her past. The book concludes with you in New York City, and you say, “I felt the future bearing down.” Speak to the idea of closure, and whether publishing this memoir offered a level of previously unreachable peace.

GALBRAITH: What a lovely question. It gives me chills, Margo. This book has brought me hard-won peace. I’m moving beyond my wounded inner child so she doesn’t hold me back anymore. I can choose to stay in this primal wound or I can choose to heal. I’ve chosen healing. Writing this book was a form of healing, but speaking about it post-publication has been where the peace really began to settle in my body.

This book taught me lessons in resilience, trust, boundaries, faith, and who has been truly there for me all along. I didn’t expect the negative fall-out from my immediate family, but it’s opened my eyes. I’m grateful to have a thriving friend and adoptee community where we can talk about our feelings without fear of abandonment. So much of an adoptee’s narrative is about being gaslighted and told to hush. We are told that expressing our feelings hurts other people’s feelings and that it’s our job to not hurt other people’s feelings. I wish more people realized the positive benefits of therapy.

LITTELL: What sort of work have you been creating, or do you plan to create, now that The Guild of the Infant Saviour is out in the world? Will you continue to combine visual art into future projects?

GALBRAITH: My next book will be in a similar vein; connected essays that push the boundaries of genre. I’ll talk about it in general, but would prefer to keep the specifics private. I plan to combine collage, erasure, sculpture, and photography along with the writing. I want to feel consumed and unbound. I’m making art now from old dolls, and a reliquary that is focused on the subject of my next book. I know already that I’ll make some collage pieces, and erasures. I see all of this being a show in a gallery that also works as complementary art for the book. Making art clears my mind. It grounds me and helps me think through questions I want to ask myself before I even put pen to page.

Margo, thank you so much for reading my book and for these smart, thoughtful questions. It’s been a pleasure talking with you and with Newfound.

Margo Orlando Littell, Interviews Editor