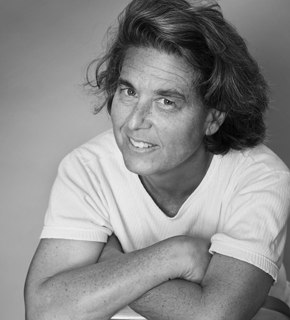

The Weight of Silence, The Weight of Words:

An Interview with Hilary Zaid

by Karin Cecile Davidson

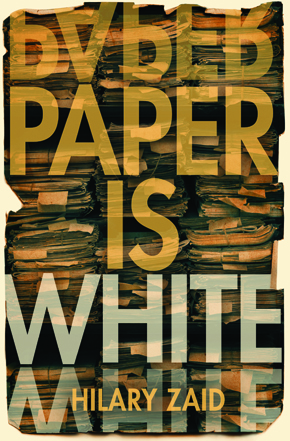

Bay Area author, alumna of Harvard, Radcliffe, and UC Berkeley, Hilary Zaid surprises, and her debut novel, “Paper is White,” is indeed an astonishing and successful surprise. Balancing weighted subjects with blue skies and beautiful slices of cake, with wedding arrangements and secret encounters, Zaid measures out humor with generosity, hope with passion, even grief with impossible understanding. Through narrative spun in first person, lead character and heroine Ellen Margolis finds her way in late 90s San Francisco, where elderly Holocaust survivors reveal their stories, relationships grow close and become divided, and the past lies like a wedding veil across the future.

Bay Area author, alumna of Harvard, Radcliffe, and UC Berkeley, Hilary Zaid surprises, and her debut novel, “Paper is White,” is indeed an astonishing and successful surprise. Balancing weighted subjects with blue skies and beautiful slices of cake, with wedding arrangements and secret encounters, Zaid measures out humor with generosity, hope with passion, even grief with impossible understanding. Through narrative spun in first person, lead character and heroine Ellen Margolis finds her way in late 90s San Francisco, where elderly Holocaust survivors reveal their stories, relationships grow close and become divided, and the past lies like a wedding veil across the future.

Ellen, an assistant curator at the Foundation for the Preservation of Memory, becomes entranced with Anya, a Holocaust survivor who hides more than she discloses. Against Foundation policy, their friendship remains clandestine, even as Ellen and her fiancée Francine plan their wedding—the place, the guests, the rabbi, the cake—and the memory of Ellen’s grandmother presses in. The wedding day nears, and Ellen discovers her emotional world has only so much room, that hidden and half-hidden truths must be uncovered and released. A beautiful tribute to love between women, inside families, among friends, “Paper is White” contributes a new definition of belonging and being to our times.

▱

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: Ellen Margolis seems, at first glance, such an honest narrator. Her way of seeing the world is forthright, reasonable, concerned, hilarious, secretive and somewhat haunted, and yet, hopeful. Though she carries the weight of memory in her personal and professional lives, she examines her inner navigations, tucking away bits of information—long-ago secrets, yesterday’s phone call, those museum visits, the confusion of intimacy for told truths—with restraint and fortitude and perhaps a touch of guilt. Her approach to life is crammed with complications—in the care she takes with Anya, in the way she sidesteps confrontations with Francine, in her exasperation and delight of longtime friend Fiona, and in her wavering sadness at the loss of her Gramma Sophie.

Tell us about Ellen, her desires and hopes, her happiness and grief, her wish for connection and for others to be connected.

HILARY ZAID: You’ve honed directly in on the central preoccupation of this novel, which is the necessity for silence and the necessity for sharing and the means to tell the difference. I don’t think it’s always clear which is better, and certainly Ellen doesn’t. And I’m so curious that you start by saying that Ellen seems such an honest narrator and then go on to describe at least half a dozen things she doesn’t share with her fiancée! Ellen is navigating two worlds: the world of a young lesbian in the 1990s, for whom coming out—telling the truth—is a path to becoming herself and claiming a place in the world; and the world of the assimilated, late 20th century Jewish American, for whom silence has been a means of escaping dangerous notice.

The novel’s title, “Paper is White,” is meant to evoke exactly this: the color of paper on which no words have been written.

Silence is Ellen’s own inheritance from her grandmother, and in seeking out the contact of other elderly Jewish people who remind her of her grandmother, Ellen finds herself working with Holocaust survivors who are ready to tell their stories; they are the living embodiment of the clash between silence-as-survival and testimony as witness. Ellen herself is about to create her own family with her partner and it feels imperative to her that she defines what kind of sharing intimacy will require for her. Despite her wish to be open and honest, her inherent suspicion of truth-telling gets her farther from that intention at every step.

That was our tradition, wasn’t it? The glint of future happiness draws dybbuks, greedy spirits who will claim whatever they can see. The old, culturally inherited fear… That, I reminded myself, was why we didn’t tell each other everything—as a charm to ward off disaster.

—Hilary Zaid, “Paper is White”

DAVIDSON: I love the time markers in this novel. Telephone booths and Sprint calling cards, crushed velvet dresses, songs by Tracy Chapman and Alanis Morissette. The recall of exuberant cries: “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!” Princess Diana’s death. “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” as a feature film. The collective decision in the late 90s for anyone and everyone to wed, to own that freedom, to become couples united in marriage, for equality that would take another ten years in California and nearly another two decades for the entire nation.

And alongside all of these is the urgent time stamp on the remaining Holocaust survivors and their testimonies, their frail and aging voices offering oral histories, for the record, so that no one will forget. Ellen collects these testimonies from men and women whose minds sometimes are lost to the present, but rooted in the terrible past. At times, the call to collect a story comes too late, the mind and body already lost to another dimension, and other times, as in Anya’s case, only part of the story is presented and in its partial telling lies sadness beneath joy.

And alongside all of these is the urgent time stamp on the remaining Holocaust survivors and their testimonies, their frail and aging voices offering oral histories, for the record, so that no one will forget. Ellen collects these testimonies from men and women whose minds sometimes are lost to the present, but rooted in the terrible past. At times, the call to collect a story comes too late, the mind and body already lost to another dimension, and other times, as in Anya’s case, only part of the story is presented and in its partial telling lies sadness beneath joy.

How do you think the passing of time and the temporal frame shape the novel, give it edges and contours? Especially in terms of Ellen, of Ellen and Francine, of Ellen and Anya? Of the future in terms of the past?

ZAID: Time frames this novel in two clearly significant ways: the end of the 20th century announces the urgency of witnessing the survivors of the Holocaust as they begin to become elderly and die; and the early days of the marriage equality movement. For the latter, it was particularly important to me to get firm about when this story was going to take place because the status of marriage equality was moving under me as I wrote the novel. At a certain point, I had to put a stake in the ground there and not worry about keeping the novel up to date with events on the ground. As for all that detail about being alive in the 90s—those days are looking awfully good right now, aren’t they?

Anya shook her head, a curt, final shake and glanced up, not at me, but at the big blue panel of sky. I looked up as a gull crossed the window: a brilliant, chalk-white mark sketched against the pure blue slate of Anya’s sky. White as a letter on which no words are written, the bird sailed on.

—Hilary Zaid, “Paper is White”

DAVIDSON: Art! Anya! The sky! There are so many references to the blank, blue, wide, incredible sky framed by Anya’s apartment window. The sky seems to echo her mind, her refusal to speak her story, and her relationship to art and the world. Richard Diebenkorn’s painting “Ocean Park #54” reflects Anya’s modern aesthetic, her way of withholding, allowing a surface view while beneath lies another painting, another version of a life.

Talk to us about Anya.

ZAID: Anya is a woman of many parentheses, from the parenthetical lines of her smile to the parenthesis of her inscrutable eyes. She holds so much history and she is not going to reveal anything that she doesn’t want to reveal. Don’t forget that Anya fought with the partisans in Lithuania’s forests. She survived the war on her own, ended up behind Soviet lines, and made her way to America, to a life that did not end—as so many of such stories typically do—with marriage and children. For Anya, silence has been a habit of survival and that kind of withholding can come to be an art. For Anya, it has been. Ellen has met her match here. Anya is a master.

I was searching for the words, words you could say without saying anything, words you could hear, if you wanted to, without hearing anything, words that would fall, if you wanted them to, like a stone disappearing without a ripple into the sky—the only kind of words I thought Anya could hear … I had to let her … measure … the weight of silence against the weight of words, and decide which was heavier to bear.

—Hilary Zaid, “Paper is White”

DAVIDSON: Ellen understands responsibility. Not just the day-to-day mundane task of earning money, balancing a checkbook and thinking about the future, but the imperfect and magical ways in which we can support and love others. She is the daughter of reasonable parents who do not understand her life choices, but who will still be there at her wedding. She is engaged to a woman who understands how order can restrict imagination, who knows how to bring Ellen’s world and her own together. And she is the collector and curator of the stories of Holocaust survivors. In the spaces between all of this responsibility, there are multiple instances of humor, the lightness and timing of which is pure and natural and utterly hilarious.

Speak to us of humor, of casting light between the more serious narrative folds.

ZAID: Like silence, humor is a habit of survival. Humor can even be a fine tool in the creation of silences! But, certainly, laughter is a way to make life bearable. If anything, I’m much more inclined to moments of humor than seriousness. It’s amazing that this novel isn’t a book full of jokes. Why did the monkey fall out of the tree?

Behind the counter at Bacardi’s, tiny mousse cakes—lemon, chocolate, pistachio, mango—floated, perfect as Anya’s little Thiebauds.

—Hilary Zaid, “Paper is White”

DAVIDSON: Why did the monkey fall out of the tree? For cake? Definitely for cake.

Cake, love, marriage. Every time Ellen visits Anya, they eat cake—sponge cake with berries and butter cream, Linzer torte, and eventually hamentaschen, a pastry with deep, emotional ties to Ellen’s Gramma Sophie. Here is the shared love of rich, sweet layers, and also the ceremony of eating together, savoring, while simultaneously knowing that their meetings are forbidden and, therefore, secretive. In essence, cake becomes complicated, for its ceremonial attributes connect it with Francine as well. All those wedding cake tastings!

I’m still convinced, Hilary, that when you go on book tour with “Paper is White,” bakeries should be included along with bookstores for readings and promotions. With every book sold, a celebratory piece of cake! In New Orleans, beignets, king cake, doberge; in Columbus, Ohio, pistachio honey pound cake and custard-filled donuts; in Manhattan, cheesecake and apricot-studded hamentaschen; in San Francisco, princess cake.

Seriously, though, cake is such a uniting factor in the novel. Explain what you’ve learned about the characters through the beautifully satisfying inclusion of pastry and cake.

HILARY ZAID: Cake is important! For a Holocaust survivor to eat rich, layered cake is to repudiate the Holocaust. Full stop. This is life, bursting between the layers. This is sweetness. This is the joy of survival, defiance of the project to starve and gas us out of existence. What could be a more ordinary joy? And for Ellen, baking was the activity through which she silently bonded with her grandmother Sophie. It was a safe, shared activity through which family and cultural history was transmitted from grandmother to granddaughter. Instead of “I grieve”: “Two cups of flour. Sifted.” So it’s only natural that Ellen and Anya share this pleasure together when, as often, they can’t quite say what’s on their minds.

Francine lies in bed. Her hand flutters, smoothing out the place on the clean white sheets where I belong. Behind her head, the dogs lie in curled, open quotations.

Papir is doch vays un tint iz doch shvarts.

Paper is white and ink is black.

Tzu dir mine zis-lebn tsit doch mine harts.

My heart is drawn to you, my sweet-life.—Hilary Zaid, “Paper is White”

DAVIDSON: “Paper is White” gives us so many gifts. One of these is the idea of intimacy. There is the intimacy between lovers—hushed, intuitive, passionate. There is that between friends, those who feel the heat of a secret and are glad to turn it over and over, burning their fingers, but never letting it outside the range of their closely tilted heads, their furtive whispers. And then there is the intimacy of revealing only a section of truth, like a slice of Anya’s Linzer torte, the layers sweet and mysterious. Inside these latter, muted stories, there exists a different kind of intimacy, one in which untold things lie below the surface, in Anya’s world, “lies of omission,” “pentimenti,” “entire worlds before your very eyes … that you cannot see.”

Talk to us about intimacy in the novel, especially in the mentioned striations, along with the moment under the chuppah, Ellen and Francine’s wedding canopy, “the place where the past stretches out its arms and becomes the future.”

ZAID: This entire novel is an act of intimacy. An invitation to share a truth. I hope readers will feel that.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor