Love and Loss Intertwined:

An Interview with Gwen Goodkin

by Karin Cecile Davidson

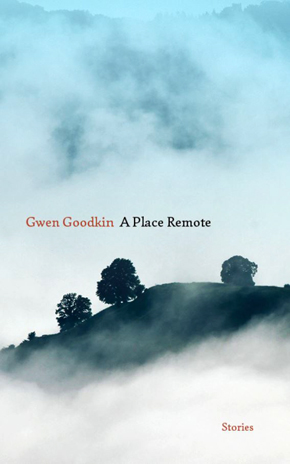

Gwen Goodkin is the author of the short story collection, “A Place Remote” (West Virginia University Press, 2020), a breathtaking and candid glimpse into the lives of those in small Ohio towns, from the university town of southeastern Oxford farther north to Mansfield and on up to the northeastern towns and farms along Highway 18. The stories appraise and illuminate the attitudes, desires, pursuits, misunderstandings, demands, and caring of their characters, who reach for more, not always finding truth nor satisfaction inside their wishes. In prose that is reflective and thoughtful, Goodkin leads us to places she knows well, to people she understands, with an awareness of and respect for their lives, whether rich with friends, complicated by struggles, or brightened by hope.

Gwen Goodkin is the author of the short story collection, “A Place Remote” (West Virginia University Press, 2020), a breathtaking and candid glimpse into the lives of those in small Ohio towns, from the university town of southeastern Oxford farther north to Mansfield and on up to the northeastern towns and farms along Highway 18. The stories appraise and illuminate the attitudes, desires, pursuits, misunderstandings, demands, and caring of their characters, who reach for more, not always finding truth nor satisfaction inside their wishes. In prose that is reflective and thoughtful, Goodkin leads us to places she knows well, to people she understands, with an awareness of and respect for their lives, whether rich with friends, complicated by struggles, or brightened by hope.

Winner of the Folio Editor’s Prize for Fiction as well as the John Steinbeck Award for Fiction, she has twice been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her novel, “The Plant,” was named a finalist in the Faulkner-Wisdom Novel-in-Progress competition, and her TV pilot script, “The Plant,” based on her novel-in-progress, was named a quarterfinalist for Cinestory’s TV/Digital retreat. She won the Silver Prize (Short Script) for her screenplay “Winnie” in the Beverly Hills Screenplay Contest.

Goodkin has attended the Iowa Writer’s Workshop Three-Week Summer Intensive Session, the Tin House Writer’s Workshop, and the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley’s Fiction Workshop. She has a BA from Ohio Wesleyan University, an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia, and also studied at the Universität Heidelberg. Gwen was born and raised in Ohio and now lives in Encinitas, California with her husband and daughters.

I stood there, unsure of what to do. I didn’t know it then, but I realize now that if I knocked on the door, she’d have to face the very thing she was hiding, that home had come to her, in spite of how hard she’d worked to cover it up.”

–Gwen Goodkin, “Winnie”

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: RJ, the narrator of the story “Winnie,” is about as upfront and natural a voice as one might find in literature. To me, he recalls the voice of Sonny in Larry McMurtry’s “The Last Picture Show,” with an honesty that’s a little staggering, given mostly to those who work relentless kinds of jobs, trucking, roughnecking, and in RJ’s case, construction, working concrete wherever the jobs take him. There’s a careful lonesomeness to this character, one that plays into the theme and concept of places remote.

Tell us about RJ, about his world, why he seeks out Winnie, and how you found his voice.

GWEN GOODKIN: With RJ, it was the other way around—his voice found me. He was insistent; his voice grabbed me and said, “Listen! You have to listen.” I came to realize that this story was his confession, his attempt to unburden himself of survivor’s guilt. He survived his abusive father—managed to get away. Not everyone does.

I love the phrase “careful lonesomeness.” RJ could have found a guy on his crew to live with, but he chose to be alone. My sense of him is that, at the point in time when the story begins, he is just starting to face his own damage, to admit its existence. And he needed the space to do that. But there’s only so much reflection a person can do, especially someone his age where friends and socializing are a huge part of life. So I think he seeks out Winnie because she’s familiar, yet offers him the possibility of an escape into another world. He’s entranced by his own fantasy of what college and its famous party life could be, then finds he has to grapple with that reality as well.

DAVIDSON: On first reading “Winnie,” I was struck at how the pacing and dialogue seemed fitting for a script. The instinctive rise and fall of the dialogue, the gesturing between RJ and Winnie, and the eventual outcome are elements experienced in drama, as well as on the page.

Was this story adapted from or for the screenplay “Winnie,” for which you won the Silver Prize (Short Script) in the Beverly Hills Screenplay Contest? And tell us a little about the differences and similarities of these storytelling processes?

GOODKIN: Yes, the screenplay was an adaptation of the story. I’ve also adapted “Winnie” into a one-act play. What I learned by writing adaptations is that, with prose, a writer can be internal and reflective. Readers are able to know characters’ unspoken thoughts and desires. That isn’t possible with films and plays. Everything is external and a character’s motivations must be revealed through action and dialogue. Also complicating matters is that, especially with a stage play, you must hold the audience’s attention. You have to keep pressure on the story—it doesn’t have much room to breathe. But what’s great about adapting a short story, as opposed to a novel, is that you can expand rather than contract. You can fill in gaps that were in the prose. What I found with the stage play was that I needed to raise the stakes on RJ and Winnie’s relationship in order to bring the climax to its full height on stage.

In both adaptations, what I felt was lost was the immediacy of RJ’s voice. With the story, we are in RJ’s voice from the first sentence, but, with an adaptation, I had to find another way in. This was a challenge because RJ’s voice is such a crucial component of the story. But that’s the nature of writing for the screen and stage. You are no longer in total control of the world you’ve created. You have to give control over to a director and actors and trust they’ll carry out your vision.

I had a taste of what that felt like after a friend had read the prose version of “Winnie.” She had a strong opinion about the ending and what Winnie’s motivations were to bring her there—an opinion that I didn’t share. I found myself arguing about my own story, which was both maddening and exhilarating. Maddening because, if anyone knew my characters, it was me! But I realized readers project their own hang-ups and desires onto characters, so what my friend knew was her version of Winnie. And I understood there were as many versions of Winnie as there were readers. What I found to be exhilarating about the argument was that this story that I’d lived with for so long was now its own entity which existed outside of me. That my story was no longer my own. Maybe it never was.

First time Poppy caught me whispering secrets in Pep’s ear, his eyes went hard.”

–Gwen Goodkin, “A Boy with Sense”

DAVIDSON: The weight of farm work, the struggle to keep going, the sweet attachment of a boy to a lone cow whose milk eventually dries up—there’s an exponential sadness to Carter’s story, “A Boy with Sense.” He has such anticipation and hope for days on the farm with his grandparents and father, which in the end leads to his emotional toughening, an edging into adulthood well before that should be happening.

Did this story arrive from your experiences of growing up in Ohio? And how did you find yourself writing from a young boy’s perspective for this particular story?

GOODKIN: I had spent a good amount of time on a dairy farm as a child and I absolutely loved the place—dirt, fleas, manure and all. Is it an autobiographical story? Not really. The farm in the story isn’t my grandparents’ farm. My parents weren’t divorced—my dad died at a young age. But that farm of my childhood eventually had to sell their herd of cows. And it broke my heart. Dairy farming is a relentless job. Milking happens twice a day no matter what—rain, snow, hail or shine. To do it as a small, family operation is nearly impossible and, in fact, often does become impossible.

I wrote this story from a boy’s perspective as a way to put distance between myself and the protagonist. When Carter is riding on a four-wheeler under a canopy of trees feeling free and exuberant—that’s me. That’s the moment in the story where we’re one person. But I would only allow myself that one moment because otherwise I might ruin the emotional truth of the story. Putting distance between myself and Carter meant that there was room for the reader to insert herself into the story.

I’ve been back to the farm of my childhood and had the chance to go inside the empty milking parlor and I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t go inside. It was too sad. I wouldn’t be able to handle the silence. For a space that had always been full of sound—hooves against cement and hot breath, the milking machines and cows talking—to go quiet? That amplified the loss.

But, in this story, the milking parlor still exists, full of life.

Us old boys look straight ahead, like we’re together but in our own separate foxholes. Or coffins. Those who cry are spared the embarrassment of a sideways glance. Those who don’t cry sweat at the effort of pushing the emotion down. The heat of it presses against my jacket. I myself don’t cry or sweat. I learned long ago how to hold it all in.

–Gwen Goodkin, “How to Hold It All In”

DAVIDSON: An all-encompassing look back at friendship, marriage, and fatherhood on the occasion of his lifelong friend Chic’s funeral, the story “How to Hold It All In” reveals the insights and memories and misunderstandings of the narrator Marv. His is a beautiful, sad, thoughtful vision of a life, and in the telling is the power of voice. Just the names of the characters—the veterans Marv, Chic, Lyle, Harold, Jinx, and Floyd, along with their wives, sisters, daughters, sons, Harriet, Rose, June, and Brice—as well as the way they speak, or don’t speak, to each other adds a depth of understanding to story. There are such wonderful details, like the strawberries found at the edge of the railroad tracks, the early days of Marv’s and Harriet’s marriage, how Chic’s and Marv’s friendship is altered.

Tell us about the use of voice in this story, about the decision to begin with the collective “we” and then transition into the first-person, singular voice of Marv, and how you came to discover and write his tale.

GOODKIN: Both of my grandfathers and a few of my great uncles were WWII veterans. When my grandfathers and uncles told war stories, at some point there would be a switch into or out of the collective “we.” One of the stories my grandpa told most often about the war was about his return home. How when his ship sailed into New York harbor and the Statue of Liberty came into view, “There wasn’t a dry eye on deck. Not a dry eye.” He always said it exactly like that, ending with “not a dry eye.” It was okay to cry in that moment because it was collective—everyone was crying. But when they went their separate ways, crying wasn’t acceptable anymore. Maybe that’s why a lot of them, my grandpa included, searched for their tears in the bottom of a bottle.

I think the collective “we” is the nature of the military and part of the training to function as a group. What happens when war is over and the group no longer exists? When soldiers come home, they have to adapt to being individuals. In my grandfathers’ cases, they had to be alone with themselves and sit with what they’d done. Who were they now? It becomes a different war then. A war of conscience and memory. And each man must fight that war alone.

DAVIDSON: In her 1972 Paris Review interview, author Eudora Welty is asked about “the function of place” in her short story “No Place for You, My Love.” She reflects in her answer on place having written the story, that place “started the story and made it for me—and was the story, really,” that “place is essential,” and “a fiction writer’s honesty begins right there.”

DAVIDSON: In her 1972 Paris Review interview, author Eudora Welty is asked about “the function of place” in her short story “No Place for You, My Love.” She reflects in her answer on place having written the story, that place “started the story and made it for me—and was the story, really,” that “place is essential,” and “a fiction writer’s honesty begins right there.”

In terms of the stories of “A Place Remote,” wherein the centering and through-line seem to come directly from the collection’s title, how would you respond to Welty’s ideas about place in fiction?

GOODKIN: My husband and I took a trip to the East Coast once, B.C. (before children), to Boston and I mentioned I’d always wanted to visit Maine, so we took a day-trip to Portland. It was early November. Portland was nearly empty of tourists and shockingly cold. We were being absolutely thrashed by the wind and ducked into a restaurant to escape. We understood quickly we were the only non-locals there, though the locals mostly ignored us. But we drank our beers and ate our chowder and eavesdropped. What I realized is that the Maine locals weren’t all that unlike my Ohio brethren, but there was one big difference—the sea. Mainers were a hearty folk, thanks to a lifetime of headfirst forays into that sharp sea wind.

The sea is a mysterious place, a dangerous place, an ever-shifting world. I have lived near the Pacific Ocean for eighteen years, but we in Southern California are not like Mainers. Our wind is almost always mild and warm. Each day starts much like the last—gentle sun, then bright sun and back to gentle sun. We are not a hearty folk.

One thing we do quite a bit out West, though, is explore our environment. Because we can, all year round. And with that exploration is a sense of discovery and adventure. We are curious about what we might find, excited in an almost childlike way to search the tide pools, discover hidden waterfalls on hikes, find tucked-away places far from crowds.

As I began to pull together my second short story collection, I realized that all the stories were set out West, some near the ocean, some in the desert and that nearly all the stories were told from a female point-of-view. Many of the stories in the second collection are fantasy/magical realism. This was a departure from “A Place Remote,” which is set mostly in Ohio, with primarily male voices, grounded in realism. When I began writing the stories in “A Place Remote,” it was with a sort of homesickness, a longing to be around familiar people. Because I couldn’t physically be with them, I wrote them into being. But, now, with this second collection, I am exploring my surroundings, the magic of the sea, the danger and the thrill of the unknown.

Life has served me up a heavy dose of reality, so I’m one of the few performers who considers any amount of time on stage to be a gift … I sing only in the chorus, never the named roles. Until now.

–Gwen Goodkin, “A Place Remote”

DAVIDSON: In the final story, “A Month of Summer,” Julian/Yulli, the narrator, on the occasion of being chosen for a solo role in Schubert’s opera “Sakontala,” recalls a time when he lived with a family in Heidelburg, Germany. The story is introduced by a quotation from Sarah Orne Jewett: “In the life of each of us … there is a place remote and islanded, and given to endless regret or secret happiness.”

What called you to write Yulli’s story? Was your own time in Heidelburg, by chance, a deciding factor? And how does place, in terms of actual, geographical place vs. places within, contribute to this narrative?

GOODKIN: When I began to write “A Month of Summer,” I was coming off a string of heavy stories and decided my next story would exude joy, either in part or as an overall takeaway. I was so invested in not straying from that intent that I made sure the word “joy” appeared up front, both as a reminder to myself and as a clue to the reader, that it would be there, I promise, just stick around for journey. When I thought back to a truly joyous period in my life, my mind went to my time as an exchange student in Germany during high school. Except I only stayed with that family for three weeks and they lived in Oldenburg, not Heidelberg.

I set the story in Heidelberg because it’s such a magical place. Even Germans jokingly refer to it as the Disneyland of Germany because it is so strikingly beautiful. In a way, it looks staged, which fits with the story’s notion of being on stage, everything arranged to appear perfect, and yet, when you look backstage or behind the curtain, it’s chaotic and messy. Yulli is very guarded about his true self, especially as a teenager. He’s hesitant to let anyone in—or, put another way, to bring anyone behind the curtain. I wanted that reflected in the pacing. I purposely made this a slow-moving story as a way to manifest his personality in the prose. Yes, the reader is getting to know him, but he’s sizing up the reader as well. Can I trust you? Will you hurt me—or will you hurt with me?

I chose to make Yulli a musician because nearly everyone in my dad’s family is/was a musician. It felt like a path I might have taken—to be an entertainer on some kind of stage, comedy or music—but it wasn’t my calling. So I decided to live it, briefly, through Yulli. I wanted him to have his moment, because I know his struggle. And, in a way, “A Place Remote” is my own moment on stage—finally, after so many years of being in the chorus, I get the chance to sing my solo, too.

I’m happy just hanging out with my kids. They’re my best friends, and, really, who needs more than two friends? … Marissa is taking careful bites [of her ice cream] and my son with those wide-spaced teeth toddlers have, ice cream like a goatee and we’re just eating, and every once in a while my son will say “puppy” or “hi!” to a passing airplane and, in between, his sounds of contentment, which are different than babbling, somewhere between singing and talking.

–Gwen Goodkin, “The Widow Complex”

DAVIDSON: A theme that runs throughout the collection is that of love. Love of family, love of friends, a child’s love of a lone cow in his grandfather’s herd, love that arrives again after it has been missing for too long, and even the love of a stay-at-home-daddy existence, thick with spider webs and diapers and playdates. Here, in “The Widow Complex,” there is a departure from the rolling hills of Ohio to “a suburban desert town,” and here, there is a narrator, highly evolved inside the love of his wife and their children. There is a beautiful clarity to the narrator’s introduction to the dangers of black widows and brown recluses, in which he asks his young daughter Marissa to identify the different kinds of webs on their apartment complex’s playground. And there is a direct, humorous way in which he defines his long days at home with children while his wife is away at work.

Tell us about love—in this story, in your past and present writing, and in literature, with literary influences in mind.

GOODKIN: What’s interesting is, if you’d asked me to describe what this book was about in one word, I would have answered loss. Loss of friendship, loss of innocence, loss of a parent, a child, freedom, sanity, love. I think the two are intertwined—love and loss. I experienced loss at a young age when my father died and I’m still grappling with the impact of that. Once a person experiences major loss, love takes on a different shape. It’s less casual and free, more anxious and fraught because the person knows how tenuous life is. Those of us who’ve experienced loss at an early age know it could disappear in a moment. We also have an acute sense of time. It’s always ticking in our ears.

One of my favorite essays is Tim O’Brien’s “The Vietnam in Me,” where he explains the concept of “war time.” About it, he says: “Almost 5 A.M. In another hour it’ll be 5:01. I’m on war time, which is the time we’re all on at one point or another: when fathers die, when husbands ask for divorce, when women you love are fast asleep beside men you wish were you.” The essay begins, however, in Vietnam in the spot of his old army base, where he remembers what an oasis the hill was to him and his buddies, where they could almost forget about the war for a few days and pretend they were at a strange party in the middle of the jungle. Later in the essay, O’Brien goes on to say, “Vietnam was more than terror. For me, at least, Vietnam was partly love. With each step, each light-year of a second, a foot soldier is almost always dead, or so it feels, and in such circumstances you can’t help but love.” To me, much of love is memory. It’s patching the holes and cracks—a cleaned-up version. A focus on the positive. Love is also an imagined future, as is the case in Sarah Orne Jewett’s “The Country of the Pointed Firs.”

Jewett’s novel is centered around a woman who spends a few months in a small Maine town in order to write. During her stay, a love interest materializes for the protagonist as a shy, yet thoughtful man. Not only does he seem like a good fit for her, his mother would be a lovely person to spend a life with, on a solitary island where the protagonist would have the space and time to write. The town itself and the townspeople offer a sort of romance as well. In short, as the reader nears the end of the book, she wants the protagonist to remain—in the town or on the island, possibly, with the man and his beloved mother. I’ve read critics’ takes on the book and most seem to be of the opinion that this book is plotless. Well, they’re wrong. It has a plot. An anti-plot. It’s what doesn’t happen—this obviously fitting choice—that drives the book to its conclusion. We want the protagonist to fall in love, with the man, the town, the island. And, in truth, she does. But her first love is herself and her writing. And she chooses that over the rest. That’s love. The hard choices we have to make. What we artists sacrifice for our art.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor