There Must Have Been Words Once:

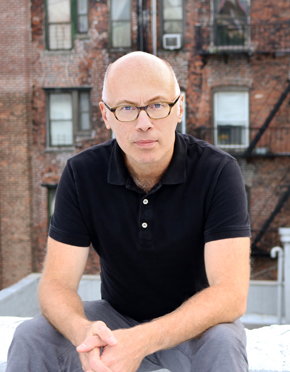

An Interview with David Eye

by Karin Cecile Davidson

The poems of David Eye’s collection, “Seed”, (The Word Works, 2017), remind us to breathe, to sit inside the shimmering, heartbreaking moment, to stop and wonder and laugh. Here is a world curtained in nature, rapture, fertility, and desire, while, beyond, lies a horizon constrained and fragile and full of possibility. Relationships—the “father, filling the doorway,” the “boy slapped into manhood,” the “pretty mother,” the “sister, nearly four,” the “smiling aunt,” the cousin “in the City,” the lovers with their “breathless kisses”—wrap themselves together, then wrest themselves apart, and we are reminded of the addition, subtraction, and division that mark a lifetime. Discovery occurs and recurs in the act of turning inward to view a past, to understand the instant when everything changed, to open and examine and somehow make peace. “Seed” reveals how beginnings are intricate, how journeys are remembered by what lay underfoot—“the sweet, sharp scent of sun on dry needles”—and how we return from the wondrous, reckless place where we began.

The poems of David Eye’s collection, “Seed”, (The Word Works, 2017), remind us to breathe, to sit inside the shimmering, heartbreaking moment, to stop and wonder and laugh. Here is a world curtained in nature, rapture, fertility, and desire, while, beyond, lies a horizon constrained and fragile and full of possibility. Relationships—the “father, filling the doorway,” the “boy slapped into manhood,” the “pretty mother,” the “sister, nearly four,” the “smiling aunt,” the cousin “in the City,” the lovers with their “breathless kisses”—wrap themselves together, then wrest themselves apart, and we are reminded of the addition, subtraction, and division that mark a lifetime. Discovery occurs and recurs in the act of turning inward to view a past, to understand the instant when everything changed, to open and examine and somehow make peace. “Seed” reveals how beginnings are intricate, how journeys are remembered by what lay underfoot—“the sweet, sharp scent of sun on dry needles”—and how we return from the wondrous, reckless place where we began.

Cousin—When a dozen robins blew into the yard yesterday—

I’d never seen so many—I watched them hop, cock their heads,

grab the thaw’s first worms. Such a pleasure, those yam-

colored breast feathers.–David Eye, “Letter from the Catskills”

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: A pair of your poems, “Letter from the Catskills” and “Postcard to My Sister,” are addressed to family members—namely, a cousin and a sister. These feel so personal, as if they are meant for the reader, and in a delicious way, voyeuristic, as if we shouldn’t be privy to them. Humor and sorrow live side by side, humor colored by joy, regret, and pure love in the letter and sorrow washed with dream and memory in the postcard.

Tell us what brought you to this epistolary form, so intimate and inviting.

DAVID EYE: First of all, I have to thank you for this opportunity, and for the depth with which you have read my book and asked these exacting questions. I will have to work hard to rise to your level! Maybe it’s because this is my first book, or because it just came out in April, but I’m still moved to learn that (and how) my work is resonating with readers.

I’m glad you found the “letter” form inviting, though I wouldn’t say that was my intention. I’m not sure I know what my intention is, most of the time! For me, this form enabled me to address two Others (who happen to be actual people, and important figures in my life) in particular and direct ways, and perhaps ways that—in “real life”—I wouldn’t, or haven’t. It’s interesting (to me, anyway) that, though several other poems in the book started out as letters, these are the only two that retained the epistolary form from their first drafts. I think the explicit physical distance in the poems might have been a factor, and I also think writing a letter requires a different voice from other poems that employ the second person. The speaker in my other “you” poems seems to narrate, or to have an omniscience, that a letter just doesn’t allow. And maybe that gets at the intimacy you describe.

In some ways, I think every poem is a bit of a love letter, from poet to reader, even when it’s not what the poem is “about.” Though in the writing I wasn’t thinking of how the poems would be perceived, I’m gratified to know that a sort of triangle was formed, and that the reader (you, in this case!) can become involved in the same intimate way as the figures on the page.

In the birthday photo, my smiling aunt

has her back to the wide-open window,

behind her the unseen Albemarle night.

Summer ’68 must have been abuzz.–David Eye, “Vietnam”

DAVIDSON: Like letter and postcard, there are also poems that take their form from photographs. In “Unspoken at JFK,” photographic images lead to surprising final lines, while “Odalisque ’76” and “Bathtub Ophelia,” respectively, are inspired by untitled black-and-white and colored photos. Calling up history and emotional territory, “Photo: Fort Sam Houston, 1984,” “Photo: August 14, 1968,” and “Vietnam” present situation and celebration—“another week’s tampdown,” “seven spoons, a stack of saucers,” and “the ghost dot on the TV screen”—inside the realm of the military, of family, with the outside world pressing in.

Mary Jo Bang, in speaking of her poem, “Portrait as Self-Portrait,” commented recently in The New York Times: “In a photographic portrait, we sometimes forget the maker exists, but how she frames her subject determines what you, the viewer, will see.”

Describe the way poetic form emerges for you from photographic image.

EYE: Because they are finite and “framed,” photos have provided me good ways into poems, whether as subject or starting place. I started several of these drafts with description: what do I see? Then other questions arise: What do I do with what I see? What don’t I see? How much do I want the reader to see? Because s/he doesn’t have the photo, I feel it’s part of my job to recreate it—or my version of it, just as the photographer has made a choice by framing her subject. I loved that poetry issue of the “Times” Book Review, by the way.

But having said all that, of the five poems you mention, only two are concerned with literal description. “Fort Sam” quickly jumps from a photo to memory, and in “Ophelia,” an abstracted photo yielded an abstract poem. But in “August 14” and “Odalisque,” the photo’s details seemed important, and I hope those descriptions lead the reader, in different ways, to a place outside the photo. And “Vietnam,” inspired by the same family photo as “August 14,” dispenses with description (and the photo itself) after the first two lines. Here, what is not depicted in the photo (nor in the poem explicitly, except in the title) is what interests me: the raging war that, as an eight-year-old, I was oblivious to.

A note about objectification when it comes to writing about art (or anything, I guess): I felt it important to acknowledge myself as one of the “gazers” in “Odalisque ’76.” I’ve made a poem about a photo that displays a Black female stripper being ogled by a bunch of White guys in a club in the ’70s. The poem turns from description to her thoughts near the end, and when she wants to “scrub off all these eyes” in the final line, I intend my own to be included. Mary Jo Bang’s comment was about the viewing of photos, but I think it also gets at artist responsibility.

there must have been words once

almost unhinged, but not quite.–David Eye, “MTA III: Crosstown Bus”

DAVIDSON: I love the “MTA” bus series—the travel, “the window seat,” the way “tree branches usher us uptown,” the interaction with other riders. But I especially love “MTA III: Crosstown Bus,” disguised as an indirect, circuitous route within the round-trip of a villanelle. Words, hope, promises, time and money: here today, gone already. Funny how such a constraint is so lively, lovely, and yet contemplative, nearly sad.

Speak, if you would, about this transit series, from your relationship with public transportation to your thoughts on poetic form. And in thinking of form, how do you decide between the rondeau, as in “A Distant Line of Hills,” and the sonnet, as in “Video Booth Sonnet”?

EYE: My thoughts on form. How much space do we have?! Form is what drew me to writing poetry. I was at first fascinated by the puzzling of it—how to shoehorn everything a poem has to say into a container only, for instance, 10 syllables wide by 14 lines long. And though I didn’t “grow up” to be a formalist (I started writing at 43), I certainly draw on metrics and syllabics and internal rhyme to help a poem cohere. I have rarely set out to write a formal poem, but have often had the experience of poems that weren’t working suddenly functioning better when I set limits. Like children who need boundaries, they started to behave better.

I have also had the experience as a reader (and reviewer) of being compelled by (and propelled through) a book by its skillful, purposeful use of form. Derrick Austin’s “Trouble the Water” is a fantastic recent example. Conversely, I have had to struggle through a book whose poems, despite earlier compelling formal work by its author, felt flaccid and uninteresting—in great part because the poems were too “loose” and could have used some structure. (And no, I’m not saying who that writer was!)

But as to my formal streak, certain themes do seem to want (and warrant) formal treatment. For me, a poem set on a bus or a train wants repetition and/or meter. In the case of “MTA III,” it was also the subject’s repeated behavior that lent itself to—demanded—the villanelle form. (It’s the only successful one I have, so far.) “Distant Line” is an example of a poem that was just sitting flat on the page until the rhyme and repetition required by the rondeau form helped shape and enliven it. Though many of my poems start as free verse, I tend to revise toward sonnet length, even if unrhymed and/or only loosely metrical. But “Video Booth Sonnet”—with its theme of a particular brand of love—always wanted to be dressed up as a formal sonnet.

When cold droplets tap my skin, I listen.

And they sound like the goodbye I dread

and long for. Rain filling cupped palms,

cooling my upturned face.–David Eye, “Village of Adiós”

DAVIDSON: Throughout “Seed,” there are clutches of poems that concern lovers, sensuality, coastal towns, desire and discovery, rain and mist, breakups. “So many breakups.” Even a poem entitled “Breakup Poem,” which becomes increasingly tragic with every line. Memory, bodies, trust, and reflection also live within these poems, even as they appear on the page, paired and facing each other. “Pond” and “Morning, Delft Heaven,” “Last Day, Land’s End” and “Night-for-Night,” as well as “There’s a Bar in Florence” and “Village of Adiós” reflect into each other from their neighboring pages, and out of these mirrors arise bodies of water, “gold squares on the silver pavement,” “a downpour.” From these we understand that “someone always leaves” and how to arrive “alone to find what we may have lost.”

Robert Hass in “A Little Book of Form” writes: “Form in the visual arts is spatial and in literature it is temporal. A poem has a beginning, a middle and an end. A work of art—whether sculpture or painting—has edges.”

Given the way in which the sequencing of poems and the ordering of words can engage the senses, and in turn call up image, depth, and dimension, what do you think of this statement?

EYE: Well—I’m not sure I fully agree with Mr. Hass. While I like his idea of literary form as a function of time (vs. space), I think poems—more than other forms of literature—can behave like visual art. (1) What is white space (around the poem, between each stanza, at the end of every line) if not a kind of edge? (2) A poem can but needn’t have a beginning, middle, and end. And (3) though a poem “ends” on the page, I agree with your implication that—through the imagery and emotional resonance evoked within a poem, through ordering, through juxtaposition—a poem or “clutch” of them can act spatially, perhaps even moreso than, for instance, a painting which is bounded by its frame.

EYE: Well—I’m not sure I fully agree with Mr. Hass. While I like his idea of literary form as a function of time (vs. space), I think poems—more than other forms of literature—can behave like visual art. (1) What is white space (around the poem, between each stanza, at the end of every line) if not a kind of edge? (2) A poem can but needn’t have a beginning, middle, and end. And (3) though a poem “ends” on the page, I agree with your implication that—through the imagery and emotional resonance evoked within a poem, through ordering, through juxtaposition—a poem or “clutch” of them can act spatially, perhaps even moreso than, for instance, a painting which is bounded by its frame.

The sequencing of poems in a book. Ugh. It’s tedious and Sisyphean work. I ordered, reordered, over-ordered, relaxed the order, and finally (with help from readers and my editor) landed on what felt like the right placement. There are groupings and there are leaps, as with memory. I know the effort was worthwhile when a reader makes these kinds of connections, when s/he finds that the poems, in their placement, “reflect into each other.”

It wasn’t until I was going through the manuscript in late phases of editing that I realized how many times and ways water appears—rain, snow, the towns where “bodies” of water edge land. Our bodies are water and yet have edges. It makes me want to look back at these “water” poems to see if there’s more to them than meets the—pardon me—eye.

And jesus, the Quilt

and stepping onto that canvas margin, like wading

ankle-deep into a glassy ocean and being pulled

under by a riptide of sorrow I didn’t see coming…–David Eye, “Negative, 1996”

DAVIDSON: When I first read “Negative, 1996,” a neighbor’s radio was playing a tune I didn’t recognize at first and then knew, from Annie Lennox’s unmistakeable voice, as “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This),” a song that brought the Eurythmics fame when it came out in 1983. And then I read, “And the letter from Berkeley in 1983 about a new disease.” The irony of the pairing, of that moment in history, didn’t slide past, and I allowed it to linger in memory of “friends, lovers, teachers, women, men.” Those who asked for sweet dreams and died instead.

In this poem, we experience absolution, sorrow, randomness, benediction, and the eventual funeral march, along with the I-persona, the one who has escaped the disease, but not the loss. “More life. The great work begins.” Yes, the final lines of Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America” come to mind. And in “Negative, 1996” and all of “Seed,” the great work continues. As Eduardo C. Corral, who selected “Seed” for the 2017 Hilary Tham Capital Collection, writes: “David Eye has crafted a debut that illuminates how queerness shapes and shelters the self. His lines are elegant, exact, and rich with both joy and sorrow.”

Would you talk about your approach to exploring queerness in art, in the LGBTQ community, and in the world, given how tangled and violent much of that world continues to be?

EYE: You do me the highest honor to evoke “Angels in America.” And how cool that “Sweet Dreams” was playing as you read “1983.” I revel in such moments of synchronicity, though they can be scary, sometimes. I love that my poem, for you, got a soundtrack by Annie Lennox!

One of the chants used by the LGBT community during AIDS and other protest marches in the ’90s was, “We’re here! We’re Queer! Get used to it!” I was in my thirties then, and probably yelled it myself at the Reagan White House. (I know I saluted with a single finger as I marched past.) But, a decade later, a “New Yorker” cartoon summed up my feelings—for a while—about being gay: Two middle-aged, upper middle class White guys on a couch, one reading the paper, the other on the phone. The caption read something like, “Yeah, we’re skipping Pride this year. We’re here, we’re queer, we’re used to it.” That glib pronouncement was funny for a minute. AIDS had been largely “contained”; ACT-UP had disbanded. But we have entered another era in which LGBTQ+ folks, despite some advances, are again threatened. (See, e.g., “deaths of transwomen of color.” See “Trump.”) No one can afford to be glib.

And so—despite the fact I have identified as some variation of “queer” for a long time, and I don’t feel I’m part of the daily LGBTQ+ struggle, and the book isn’t (to my mind) “about” being queer—the gay love poems made it in. And the sex poems. And breakup poems. And poems about AIDS. I look at these as not being solely about my experience, but as poems of witness. And sometimes, just when I doubt their importance, something will happen that lets me know they have a place. This interview, for example. Or the middle-aged straight man who came up to me in tears after a recent reading. Or the old man who thanked me for speaking my truth—a truth he has been unable to voice. These “personal” poems are how I have voiced the “political”—so far.

But in hottest summer, jar flies—what she called cicadas—

still punctuate the day. The whippoorwill announces

every evening, the cadence of crickets and katydids all night.–David Eye, “If We Went Back to Maple Ridge”

DAVIDSON: Past, present, and future find voice in poems of childhood and memory, love and regret, hope and testament. And winding its way through this lifetime is always the scent and residue of nature, “a lone white pine,” “the swift stream,” “the unequivocal rain,” “stars in the West Virginia heavens.” From the beginning “Frontispiece: Picea excelsa” to the ending “Epilogue: As New York Snow,” the journey is one of a son learning his father, how division is a natural event, sometimes forced too early, and the road is rugged and beautiful and edged with the idea that, yes, it’s okay to trust in “noonday meadows,” in “an impossible blue sky.”

What would you like to tell of this journey? Please include tales of all artistic endeavors—acting and singing, perhaps—and who you’ve met along the way.

EYE: I think this is the hardest question of all. Some of the “journey” is in the book, in snapshot, capsule form. But there are big chunks missing. There’s only one poem, for example, from my four years in the military in Texas. I haven’t written at all about my acting career; just as I don’t tend to like poems about writing, I’m not sure my former career will make for interesting poems—or terribly interesting reading here. But I will say this: 17 years as an actor/singer must have inspired and informed my love of language, and I feel I’m only beginning to tap the stores of lyric, music, and line from those years in New York City.

My career, though pretty steady, was marked by a lot of “downtown” (Off- and Off-Off-Broadway) theatre that rarely paid much, if anything, and then an improbable, er, leap into the Broadway tour of “Cats.” That was followed by some bad luck with agents, more (less recognizable) tours, more Off-Broadway, and a couple of roles on Law & Order and SVU. In short: a lot of striving; a few moments of ecstacy; some disaster (there is no terror like the terror of forgetting lines); and a lot of work I’m proud of in shows that never saw the (commercial) light of day.

And then I started writing and have found community like I never knew as an actor. I do miss singing and have been looking for ways to get that back into my life. In fact, I’ve incorporated a few sung lines into recent poetry readings. And I appear to be writing a musical.

I grew up in a small town in rural Virginia. We didn’t have stoplights till I was in my twenties. I grew up Baptist, but luckily we spent the weekend at my grandparents’ farm (“Maple Ridge”) at least as often as we went to church. I’m sure all those nature poems got their start there. This comes to you from my place in the Catskill mountains, where my next nature poems (and that musical, in part about the Catskills) will come from.

As for “love and regret,” though there are more breakups than weddings in the book, it’s mostly because poetry gives me a place to put sorrow. And because I think joy is harder to write. I’m always gratified when the hope in the poems comes through.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor