The Surprise of Survival:

An Interview with Chaney Kwak

by Karin Cecile Davidson

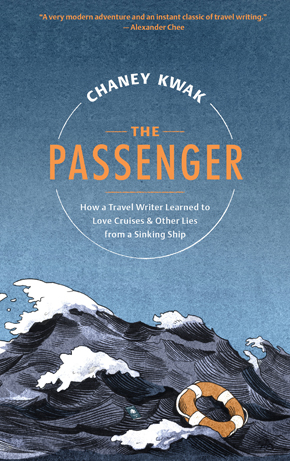

Chaney Kwak’s compelling and beautiful debut book, The Passenger, (Godine, 2021), flies beyond the classifications of memoir, travel reportage, and marine history to something more intense, wry, and personal. Even the book’s subtitle, “How a Travel Writer Learned to Love Cruises & Other Lies from a Sinking Ship,” might lead one to place the story within a category, but seriously, it’s just not that simple. Kwak’s story of surviving an intense storm at sea off one of Norway’s rockiest coastlines aboard the Viking Sky, a cruise liner carrying nearly 1400 passengers, is one that reaches beyond the fury of 65-meter swells and 75-km winds into the calm, genuine understanding of what is worth living for. “The Passenger” uncovers the surprise of survival and the realization of how life might truly be lived.

Chaney Kwak’s compelling and beautiful debut book, The Passenger, (Godine, 2021), flies beyond the classifications of memoir, travel reportage, and marine history to something more intense, wry, and personal. Even the book’s subtitle, “How a Travel Writer Learned to Love Cruises & Other Lies from a Sinking Ship,” might lead one to place the story within a category, but seriously, it’s just not that simple. Kwak’s story of surviving an intense storm at sea off one of Norway’s rockiest coastlines aboard the Viking Sky, a cruise liner carrying nearly 1400 passengers, is one that reaches beyond the fury of 65-meter swells and 75-km winds into the calm, genuine understanding of what is worth living for. “The Passenger” uncovers the surprise of survival and the realization of how life might truly be lived.

While living in Berlin, Kwak entered the world of travel writing with a story on an abandoned East German amusement park for The New York Times. He ventured on with publications like Condé Nast Traveler, Food & Wine, Travel & Leisure, and a number of National Geographic anthologies, one of which he found on board the Viking Sky. His fiction has appeared in Zyzzyva, Catamaran Literary Review, Gertrude, and other literary journals, with a special mention from the Pushcart Prize. A winner of the Key West Literary Seminar Emerging Writer Awards, Kwak has received scholarships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was a Friends of the San Francisco Public Library Brown Handler Resident. After his travel-writing assignment to cover the cruise along the Norwegian coast ending in 27 hours of drifting in storm-tossed seas, he returned to San Francisco, where he now devotes his time to beekeeping, writing, and teaching nonfiction writing at Stanford Continuing Studies program.

March 23, 2019 – 1:58 PM – As the cruise ship nearly tips over, the horizon that once bisected my lovely balcony door rises like a theater curtain and disappears. Now the sea is the stage. I tumble off my bed onto the floor and roll like a stuntman.

–Chaney Kwak, The Passenger

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: The pacing of The Passenger is smartly constructed, with time stamps marking the 27 hours of the harrowing events aboard the Viking Sky during March 23-24, 2019. The jolt and surprise of the first scene slows to a calm, background passage or three and then, just as suddenly, the writing pitches and rolls again—the narrative introducing us to what’s a stake—a lot!—and progressing in the same way that the storm does, building momentum, tossing and crashing, finding a moment of stillness, then plunging back in. It’s all unbelievably frightening, compelling, and beautifully written, and the movement through the story is much like being right there in that very ship inside that storm at sea.

Chaney, there’s so much to admire in how you placed all the details of your story onto the page. What was it like to write of this experience?

CHANEY KWAK: Thank you for the kind words. I think the word “cathartic” is overused, but I do think it helped me as a person to recast the experience through a more objective lens by writing and, more importantly, cross-referencing hundreds of news articles. Through that process I got to appreciate the rescue workers and volunteers who worked tirelessly all night to ensure safety.

Then, taking one last look around the cabin, I leave behind my money and camera, but stuff my passport down my crotch. We have drifted so close to Norway’s shore that I can almost make out the jagged outline of each boulder. At this rate, the reefs will shred this ocean liner into scrap metal and the currents will scatter all its contents. Wherever I wash ashore, I want my parents to at least know it’s me.

–Chaney Kwak, The Passenger

DAVIDSON: “The Passenger” is dedicated to your parents—“For my parents, survivors”—and the book reaches into quiet, intimate corners of times with your mother and bright, surprising moments of family history. Survival is connected to relationships, to the ancestry of survival, to the understanding of Korean origins and where you’ve come from. There is the reach for second chances. And there is the memory of your paternal grandmother’s wisdom, learned from her mother-in-law, your great-grandmother: “At least fire will leave ash… Water will erase everything without a trace.”

Tell us about how the immediacy and distance of family came to mind during the storm at sea, once you returned to shore, and in the writing of the book.

KWAK: Family—both mine and also as a notion—has always been one of my primary fascinations, and I can’t imagine writing a book that doesn’t wrestle with what family means to characters, including the narrator of the book (who happens to be me). But having some distance is helpful (both with how we deal with our families, and also with writing about them). The pandemic lockdown meant I wasn’t able to see them for long stretches of time, and that gave me the wider lens I needed in order to capture glimpses of them that weren’t colored by my immediate impressions.

DAVIDSON: The detailed marine history and the accounts of other ship disasters, such as the RMS Lusitania, RMS Titanic, HMS Barham, as well as the Gonron Maru and the Ukishima Maru, reveal all the reasons why we might want to stay on dry land.

DAVIDSON: The detailed marine history and the accounts of other ship disasters, such as the RMS Lusitania, RMS Titanic, HMS Barham, as well as the Gonron Maru and the Ukishima Maru, reveal all the reasons why we might want to stay on dry land.

The research for these accounts must have been completely consuming, but even more so the experience and time of locating and interviewing those involved in the sea-and-air rescue of those aboard the Viking Sky. The labyrinthine combination of these efforts is dizzying and reveals acts of intense bravery, stamina, and human kindness.

What else did you discover inside of all this research and in your interviews?

KWAK: For one, I realized cruise ships are constantly mired with incidents that go unreported by the media. Then again, that’s the case with any kind of accidents, right? We pay attention to huge calamities, but if you tabulate all the mishaps and troubles, they add up to far greater casualties. And that’s part of what I try to tackle in my book. Most of us are just footnotes in history, if that. Knowing how lives go unnoticed by the world—that’s both overwhelming and assuring to me.

DAVIDSON: Humor! Much more than comic relief, the humor is direct, dark, adroit, even ironic. It rings in the Norwegian ship captain’s addresses to all on board during the storm: “I am somehow keeping the ship under control.” It exists in the fact that the Success Cake served on board was not really securing the journey’s success. And it raises a laugh inside the “travel industry adage that cruises are for ‘the over-feds, the newly-weds, and the nearly-deads’”—the last a little too close to the truth for much comfort.

Where do you find the landing place for humor—in writing, in life, at sea?

KWAK: I’ve honestly never thought about this. Humor’s the other side of the same coin as pain, and I guess I see both of those things in nearly everything I see. I don’t want to force humor where it doesn’t belong in my writing. I just happen to see dark humor everywhere because pain, too, is ever present.

Are twenty-first century humans unique in our ability to equate our fantasies with facts? Have humans only recently become this stubbornly and blissfully inoculated against reality? Or is this a necessary byproduct of the foolhardy imagination that created art and landed us on the moon?

–Chaney Kwak, The Passenger

DAVIDSON: As you wrote, while the Viking Sky was pitching about in the storm, Twitter was taking off with its “alternative facts” and “toxic sludge of statements” and “half-informed beliefs about what must be happening on board.” You remark on how social media has changed the idea of time—what it takes to create an article, an essay, or a story of meaning, whether days, weeks, or months—and how all that has changed within the digital bluster of immediacy.

Most of us as writers have a love-hate relationship with all social media. What is your take on this flighty informational world in retrospect and now that you have a book in the world?

KWAK: The month leading up to the publication date was the toughest because I felt like a complete hypocrite. On the one hand, I’d been on a soapbox raving about how social media inflames narcissism and human’s propensity toward rumors; on the other hand, with the impending book launch, I was parroting all the social media tropes—selfies! funny videos! daily Instagram Stories!—to get the word out. Then, I just stopped. I think many writers go into that delicious state of indifference and calm at some point. I did, anyway. Social media is one of the things I parody in The Passenger for sure. But having gone through the motions of being a wannabe (and utterly failing) influencer, I feel exorcised. I honestly have no opinion on social media other than that I’m glad that I go for weeks without logging on these days.

Moby Dick is the Russian roulette of literature: you never know if you’re about to get suspense, biology, poetry, or maybe for niche readers, erotica. And don’t you forget: the book also features what might be the first gay wedding in Western literature.

–Chaney Kwak, The Passenger

DAVIDSON: You write of “Moby Dick,” “the book I bring on long trips,” and I admit I did laugh out loud. On a cruise, of course! But then you point out Melville’s chapter “dedicated to the color white.” There’s a deft turn here as the concept of “whiteness” leads toward cruise lines and their reflective white paint, to “inoffensive blankness,” to Melville’s worldview of the human race’s dividing lines, light to dark, to the Viking Sky’s strata of crew members, the lightest at the helm, the darkest belowdecks, manning the engines.

What is the lingering impression of this realization of the extent of stratification in the world, even aboard ships, of the moment you walked the corridor to find your copy of “Moby Dick,” passing by all the crew that you otherwise might never have seen?

KWAK: Since the book came out, some cruise fans have been vocal online—on, yes, the Baby Boomer social media platform of choice, Facebook—about how they just couldn’t relate to the book at all. Among the many things they took umbrage to, one was my characterization of cruise passengers. Truth is, I don’t think I characterized passengers. I simply wrote the few things I observed in very specific people. In fact, the book has very little to do with other passengers, to be honest. I was more fascinated with crew members, rescue workers, and, well, people who weren’t there—like my family. But I think, part of what struck such a nerve was my discussion of visible and invisible privileges aboard a cruise ship.

I’ve read pieces by other people about cruises, sure. Very few, if at all, mention class, and certainly not race. Fine, I chose to go there and point out that the upstairs-downstairs dynamic in the cruise industry reflects the inequalities of the world, and how the lines are often drawn along the color lines. It’s hard not to see the baggage of the white supremacy that persists from colonialism. But not writing about race, class, and global inequalities in a book that takes place on a cruise ship would have been just as much a choice. If a writer chooses to not discuss it or, more interestingly, not see it at all, then that is a political statement in itself.

So yeah, bring on the criticism about how it was uncouth of me to point that out. If they just don’t get it, that says a lot about that person.

What I really want isn’t to simply write books and have them published. It’s to dream again. To believe in the written word and not merely add to the cacophony of noise overflowing from our digital world. To hold something and not be ashamed to admit I gave my all to it.

–Chaney Kwak, The Passenger

DAVIDSON: Within the cartography of places a mind travels on board a ship in trouble, we come to understand the heartbreak of writing for a living, along with the fear of heartbreak enough to remain inside a relationship that is, in and of itself, very much like a sinking ship.

How are you feeling these days about writing, about love?

KWAK: I feel relaxed. I used to think I needed to publish in order to have a purpose in life. As I got older, I got to realize writing is one of the many things I happen to cherish in my life, but I may never get to write something I think is worth sharing. And if a fortuneteller told me I’d never publish another book, I’d shrug and say, okay. And that’s how I feel about relationships, too. I used to think I had to be in one in order to be worthy of… I don’t even know what. Life has taught me that’s not so.

DAVIDSON: What are you excited about now, for the future? And what’s to come? A story collection, a novel, or perhaps a memoir on pandemic life with the sweetest of company, your bees, or perhaps even sweeter company?

KWAK: I’ve seen too many of my writing projects wither and die prematurely, so I don’t know if there’s much to be said about it. Right now. I’m taking a break from a novella about the Korean diaspora, an abandoned film set in Central California, beekeeping, Executive Order 9066, and the rising sea level. I’m very content not having a deadline.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor