Daughters of the Animal Kingdom

Bonnie Jo Campbell

I.

Say you’re the middle-aged only child of an increasingly fragile mother who can no longer chop her own firewood, lug bales of hay, or—though she is loath to admit it—even harvest the honeycomb from her hives. For the past two months, since you decided to take some time away from your entomologist husband, a full professor in the department where you are an underpaid adjunct, you’ve been living in a camping trailer on the family farm, and now your mother has found a breast lump and says it’s nothing, says she wishes she’d never mentioned it. She seemed unmoved when you initially howled at her in exasperation and pantomimed clawing your head with your fingernails, but she is scheduled for surgery this week. Also, let’s say the youngest of your own four daughters has become pregnant and every phone call ends with her hanging up on you because you don’t understand what she’s going through, what she’s trying to achieve, holistically, by becoming a vegan so as not to poison her baby, physically or psychically. No meat or milk, no eggs, no honey—though you made sure she spent summers on her grandmother’s farm, where she learned to process raw honey using the crush-and-strain method as well as to make butter out of the fresh cream from a sweet-natured milk cow named Bambi.

And say, meanwhile, in your mother’s henhouse, your respite from the world of humans—you carry a book in there sometimes—there’s this screwy little Silkie with white feathers on her five-toed feet and more feathers sticking up showgirl-style on her head, and she’s just decided to hunker down in a nest box and peck anybody who touches her. She stays on that nest all night without food. She pulls out her feathers and warms the eggs against her bare flesh.

In this same henhouse there is also one Barred Rock rooster lording it over the dozen hens, squiring them to and fro. Sometimes you toss a handful of straw at him, tell him if he doesn’t behave, his sky will fall. In truth, that black-and-white rooster reminds you of your husband, who has young women gathered around him after every class and during office hours. He was your own professor when you were a young single mom, but he has remained a charming, slender man while you have grown fat and grumpy like your mother. He’s suggested you skip dessert, and this year gave you a gym membership for your birthday. You used to think it merely absurd, the effect he has on college women, until you spotted his Audi outside a café in Texas Corners, miles from campus. You were headed for the Cheese Lady shop to satisfy a craving for Maytag Blue—something you haven’t wanted for years. You were surprised to find him there, and he was every bit as surprised to see you, as was the girl beside him in the booth.

When you try to convince your youngest daughter to supplement her diet with some eggs for the easily digested protein she needs at this time—free-range organic anti-cruelty eggs, you suggest—she informs you that the whole poultry enterprise is immoral for what it does to the males. You are not feeling terribly sympathetic toward the male of any species just now, but you know it would be unconscionable to share with Rosie the particulars of her father’s adventure. Your daughter knows you’ve gone to stay with your mother, and you’ve suggested it’s a sort of spiritual retreat on the farm, a response to the nest emptying, a desire to get your hands dirty. And you would not, especially, share your most shocking personal revelation, that a stout woman in her late forties with arthritic joints and age spots can get pregnant. You reflect that in the animal kingdom, females usually reproduce until they sputter out and die.

The broody Silkie guards her clutch against the other hens, knowing some of them steal eggs—tuck them under their wings the way running backs stash footballs—and start sitting on the stolen property themselves. Though normally a hen’s poops are dainty pastel blobs, while she is hunkered down she will be constipated for long periods, after which she will shit stinking manly loads. All broody hens have their hackles up, but some lose their bird brains before the three weeks are over and break their eggs in a fit of madness. An especially crazy one might attack the other thieving hen bitches or even the rooster, disturbing the peace of the henhouse, a kind of peace for which you imagine many women would give their egg money or even ransom a child conceived late in life.

II.

My mother has long assumed she’s immune to the ravages of mortality, but an investigation of the recently discovered lump has meant a whirlwind of tests and doctor visits, a diagnosis of breast cancer, and, finally, yesterday, a left-side mastectomy, to be followed by a three-day hospital stay, during which she is very cranky and during which I have to watch my two grandchildren, as usual. My oldest daughter, who works as a physician assistant in an office across town, relies on me for babysitting Monday, Wednesday, and Friday because I teach three sections of biology only on Tuesday and Thursday and so must have loads of free time, and this would be the case if I didn’t assign any homework or write lectures. She smiled dismissively when I said last week that I would really like to finally finish my PhD in zoology. While the children and I are waiting in the lounge for the nurse to finish torturing my mother, I sort through the Scholastic books on the kid pile to find The Encyclopedia of Animals. Julianna points excitedly at the tigers, but I flip the pages until I find a brown-and-gold tree snail with a speckled foot.

“I don’t like snails,” she says. “I like the tigers. And horses.”

“That’s because you don’t understand snails,” I say. “Let me tell you a story.”

“You never tell the story in the book. You make things up.”

“Listen, Julie,” I say, and I turn the book upside down in my hands. “Most terrestrial pulmonate gastropods are hermaphrodites.”

Eight-year-old Julianna stares at me dully, as though I am speaking a foreign language. What kind of science do they teach kids in school now? For all I know, they’ve just thrown in the towel and gone back to the Bible. At this age my youngest daughter loved science, and it has only been in adulthood that she has followed every crackpot theory the wind blows her way. She says she believes that toxins can be drawn from the body by pure thinking, that quartz creates a healing aura. Or is it a healing force field?

Alex, who is four, has found a toy consisting of spools that slide along curved plastic-coated rods, and he is working at it with an unsmiling intensity. I put my arm around Julianna, though she seems disinclined to snuggle. “Why does the book have to be upside down?” she asks.

“Snail mothers lay eggs containing only daughters,” I continue. “And everything is fine until those daughters start thinking for themselves. They get it into their knuckle heads to grow penises. Can you believe that?”

Julianna looks up at me in alarm, as do two graying women sitting nearby, who resemble each other enough they could be sisters. When Alex can’t get a spool to slide onto a certain peg, he pounds it with a hardcover volume of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books.

“Even the freshwater non-hermaphroditic gastropod mollusks change sex now and again,” I say, and Julianna sighs. I do miss conversing with my brilliant husband, sharing the language of science, more than I miss living in his high-ceilinged house on the hill, which has never quite felt like home to me. The walls are painted pale green and yellow to harmonize with the Audubon and Ernst Haeckel prints. We both love scientific investigation, but I have always taken pleasure in the messier aspects of the natural world, the anomalies that lie outside the usual patterns.

“Apple snails change from female to male, but you will notice they always come back again,” I tell Julianna.

The women look at one another, and I wonder if they might be a couple. In a few years, my hair will be as gray as theirs.

“When snail eggs hatch, the daughters are transparent, almost invisible, and so you can’t blame their mothers for not noticing them sneaking out at night. The daughters whisper to one another, tell a story about a single glass slipper and a handsome snail prince whose shell features all the colors of the rainbow.”

“I wish I had my unicorn,” Julianna says. “Can we go home and get it?”

“But mother snails move too slowly to prevent their daughters’ foolish behavior. Snail mating takes twelve hours, but there’s no sense giving a girl a talking-to when she is already in the back seat of somebody else’s shell.”

The women have come around and are now smiling. I address them when I say, “Snail mating doesn’t look erotic unless you speed up the film. And then, wow!”

One of the women gets up and stops Alex’s pounding by gently removing the hardcover book from his hand. When I see my mother’s nurse walk by, I put down The Encyclopedia of Animals and take the children’s hands and lead them back into my mother’s hospital room.

“Did you know that the French keep their snails in cages woven of wine-grape vines?” I ask my mother when we run out of conversation. She is switching television channels as if trying to switch me off. She’s got a drain tube full of watered-down blood showing through the armpit of her gown, where they removed her lymph nodes.

“What the hell do people watch on TV?” my mother asks. She doesn’t have a television at home. She stops clicking only when the nurse brings her lunch, some kind of whole-wheat pizza, a banana, and two cartons of milk.

“Listen, Mom, true story. Frenchwomen pay big money to lie on the ground inside the snail cages and have the snails crawl over them. Beauty slime is the great secret of Frenchwomen. They take their daughters to snail farms on their fifteenth birthdays.”

“When you were fifteen, I dragged you out of that van parked in the driveway,” my mother says, and I can feel how hard she is working to muster the energy to harass me. Her voice has grown more gravelly over the years from working as a horse show announcer and for a while as an auctioneer. “Remember? I kicked your ass, but it didn’t stop you from becoming a teenage mother.”

“I remember,” I say. When my own youngest daughter was fourteen, I dragged her out of a guy’s car and afterward made her sit and talk to me at the kitchen table. I didn’t tell her father, but she said she’d never forgive me for embarrassing her in front of the boyfriend, and after four years she still hasn’t, though that boyfriend is long gone. If I’d kicked her ass, would I be forgiven by now?

“Did you bring me a shot of brandy?” my mother asks.

“During World War Two,” I say expansively, using my teaching voice, “in some of Europe’s densest forests, both Allied and Axis women fended off starvation by eating the common garden snail, cornu aspersum.”

Alex squirms out of my lap and runs into the bathroom and slams the door. I hear him turn on the water in the sink and the shower. Julianna looks up from her crayons and paper to stare out the window into the old Catholic graveyard. She’s holding a little stuffed bear close to her chest, but I can feel how she regrets this morning’s decision to choose the bear over the unicorn. The rule with this grandma is one stuffed animal per kid per day—it’s all I can keep track of.

“They say women who ate snails were able to remain calm during even the worst of the bombing.”

“Escargot,” my mother says. I have tricked her into showing an interest.

“Some hallucinated about world peace,” I say. “Others hallucinated about melted butter.”

“Snails probably taste better than the crap they’re feeding me here,” my mother says. “They call this pizza?”

“You seem to be eating it,” I say.

“This milk is skim, tastes like water. Go find me some salt, will you? And a couple shots of brandy.”

“You’re not supposed to have salt.”

“I’m not supposed to have cancer, either. If you don’t bring me some brandy, I’m kicking you off my property.”

“It’s my trailer, Ma. You can’t kick me out of my own shell.”

I extract a little airplane bottle from my jacket pocket and hand it over—she’s been asking for brandy since last night. I give it to her not because of her threats, to which I’m as immune as my four daughters are to mine, but because, as she says, she’s not supposed to have cancer. Just as I’m not supposed to have what I have. She secretes the little bottle under her blankets. When she continues to stare at me, I hand her the second bottle, plus a few packets of salt I swiped from the cafeteria. The smell of liquor has made me sick lately, and even the sight of the bottles makes me gag.

“You should go back to your museum and your husband. He called this morning, just to check on me. He’s a charming man.”

“He’s charming, all right.”

My mother refers to our house on the hill as the museum because of the way the prints are all framed and the way the wood floors shine. Her house is all knotty pine with dusty horse-show posters thumbtacked in place, seven-foot ceilings, and clutter that’s lain unmolested for decades.

“What did he do to piss you off so much?” she asks.

I kneel down beside Julianna and borrow her crayons to draw a picture of the brown-and-gold tree snail, and then I draw a slug, pressing hard with brown and then purple to suggest a dense, moist blob of a body. Pity the slug with no house on her back, no camping trailer in which to hide—she is all sex and no safety. And the semi-slug as well, whose ancestors were snails, but whose shell has shrunk over the generations until she sports nothing more substantial than a jaunty calcified cap. Neither slug nor semi-slug has any protection against another slug following her glistening trail, and that is why you will often find a slug with a love dart sticking out of her head.

My students never believe me at first about the love dart, the gypsobelum, that needle-sharp arrow made of calcium or cartilage. A snail or slug will shoot the dart from its body like a hormone-slick porcupine quill to subdue the object of its desire. Sometimes they don’t believe me until the quiz, though I’ve drawn love darts on the board and explained how they can be long enough to pierce a semi-slug’s foot, pinning her to the ground. A love dart can take an eye out. In all fifty states, it is against the law for a person to shoot anything resembling a love dart at another person, but there is no such law protecting the daughters of the animal kingdom.

“What’s that thing sticking out of the snail’s head?” Julianna asks, pointing at my picture.

III.

“Thank you for talking to me,” my husband says a few hours later when my mother hands me the phone from her hospital bed. “We really do need to talk. Mailing me a photocopy of your pregnancy test is not the same as talking.”

“I’m not ready to talk to you yet. Especially not here. Or on the phone.”

“Humph. Your mother sounds relatively upbeat, says her prognosis is good.”

“Invasive ductal carcinoma,” I say. “They took it out before it was too invasive, before it had arms or legs or a heartbeat.”

“Humph,” he says again, which is what he says when he is moving past something he doesn’t want to hear. “Good thing you got her to the doctor when you did. Turns out we all have a lot to be grateful for this year.”

“I suppose you think it’s just a myth that black widows kill and eat their mates,” I say. I have avoided talking to Gregory in person or on the phone because I’m not ready to be reasonable and positive with him—his reasonableness and positivity can feel like a kind of bullying. Face-to-face the man can cajole me into anything. I have always loved his clear, intelligent voice, but being away from him has given my mind a vacation, a license to roam grumpily from idea to idea all day. I’m not ready to even think about divorce, but lately I wonder if I wouldn’t rather be his student than his wife—I’d listen for a few hours, take notes, then be free of him until next week. Or maybe I just need a few more months alone in my trailer. Or I need counseling. Or a punching bag with Gregory’s face drawn on it with a crayon. Tomorrow I’ll ask Julianna to draw Grandpa for me. She is now drawing a purple unicorn, like the one she left at home.

“Why are you talking about spiders?” Gregory asks.

“I’m teaching spiders. The black widow males are skinnier than the females, and they grin too much. Maybe that’s why they get eaten.”

“Humph. I’ve always suspected the phenomenon has something to do with being observed in a terrarium in a science lab.”

“The Heisenberg uncertainty principle?”

“The observer effect. My students confuse those all the time.”

I flush with embarrassment, because I know the difference. It is a little-known fact that pregnancy lowers your IQ—it is a phenomenon too dangerous to study.

“Gregory, you can’t deny the facts. They really do devour their mates. If only by accident,” I say, though I seriously doubt it’s an accident. Practical-minded spider mothers teach their daughters to spin silky threads as strong as steel wires and sticky enough to capture prey. Surely these mothers tell their daughters that if they do happen to liquefy the internal organs of a mate, they should go ahead and drink up that protein-rich soup, for in this way the male can help create stronger, healthier eggs. What father wouldn’t want each of his hundreds of offspring to have all the advantages?

“Let’s stop with the spiders?” Gregory says, in a tone he’d use with a student disrupting his class. But then he softens his voice. “I’ll admit I’m feeling giddy at the prospect of being a new father again.”

Uncertain what noise a black widow makes, I utter nothing. My mother watches me intently, and I’m pretty sure Gregory hasn’t spilled the beans.

“I know you’re still mad, Jill, but it’s time to come home. We’ve got to work this out together. I don’t know if you can imagine how sorry I am about what I’ve done.”

“I can imagine,” I say and sigh. My mother smiles.

“I think,” he says. “No, I’m sure this baby will be good for us. I’m ready to spoil you completely, more than ever before. And I’ll start by making you those cheese crepes with raspberries.”

He did spoil me in the nicest ways whenever I was pregnant. I’m trying to stay angry, but his weeks of apologizing have worn me down. His bubbly nature makes his students love him from the first day of class, and even after all these years, I’m not immune. He’s still the delighted boy who’s been out trapping green frogs in a wooden box and who calls the whole neighborhood over to marvel at a deformed specimen with an extra set of back legs.

“A baby will be just the thing for us,” he says. “A newborn is a new start, another chance at perfection. You always felt great being pregnant, after the morning sickness was over.”

It’s true. In my twenties, I did feel great, knowing I was built to be a mama. My body surged with hormones so thrilling that I could ignore most of my discomfort and the way I forgot things. His excitement is infectious, and I think this might all be okay after all. Gregory cooked me sumptuous treats all those years ago and never mentioned my weight. My skin and hair glowed, and when I complained of morning sickness, mostly it was to get attention or to make a joke. I wonder if there’s a vegan version of those cheese crepes with raspberries we could make for our youngest daughter, who is on the verge of becoming a big sister as well as a mother herself.

“We might have a boy this time,” he says. “The chances of having five daughters and no sons is only one in thirty-two.”

“Still a fifty-fifty chance for each,” I say, glad I can be the reasonable one for a change. I’m feeling butterflies in my stomach, as I did when I glimpsed his handsome face in the hallway at school yesterday. For the record, it’s the egg-laying female butterflies who appear to be fluttering aimlessly. I slipped around the corner so he didn’t see me.

“And if you have to stop teaching for a while maybe you’ll finally have time to finish your PhD.”

“You mean while I’m nursing?” I look down at my poor breasts beneath my sweater, which is stuck with bits of hay, and I imagine my breasts swelling with milk again—the swelling had been nice. “While I’m walking the baby around at night trying to get her to sleep?”

“Or him,” my husband says. “Think positive. Assume this will be an easy baby. We’re awfully experienced.”

“Yes, awfully,” I say, but he is right. We could be smarter parents this time.

“It’s a big surprise, Jill, but I’m excited. Aren’t you?” he asks. “Of course, there are risk factors, just because of your age, but we’ll get all the testing. We’ll be very careful about this.”

My mother is screwing up her face, listening from her bed. She can’t see that all around her left shoulder the sheet is now smeared with diluted blood. Only after I get off the phone do I realize how I am smiling. I didn’t even think to say to my husband, You’re no spring chicken, either, pal.

Carrying an infant around at night through a silent dark house is another experience I’ve secretly enjoyed, so much so that some nights I stared at one or another of my baby girls in her crib, wishing I could pick her up without waking her. But the baby my arms have been longing to hold is my daughter’s new child, not my own.

IV.

My mother is just home from the hospital when the veterinarian, Lola Hernandez, shows up to castrate Jack the donkey. My mom remembers the appointment only when the late-model white pickup pulls in the driveway.

“Let’s put this off until another time,” I suggest.

“If that horny son of a bitch breaks down the fence and breeds Drew Anderson’s mares, that man will sue me for the cost of a half-dozen show horses. Not to mention poor Chrysanthemum. Just go give Lola a hand. Or else I will.”

Gregory has taken issue with the language my mother and I use about castration, in saying we are “fixing” the male animal. For eighteen years he has also avoided discussion of having a vasectomy. The talk makes him squeamish, he says, and he smiles a charming smile.

“Grandma, what are you going to do to Jack?” Julianna asks me.

“Your nana will explain it.” I can too easily imagine my mother dragging herself up to the barnyard in her nightgown, trailing her drainage tube, so I put on my boots to go outside.

“Don’t let him go down,” she shouts when my hand is on the doorknob. “Keep him on his feet and make him walk around afterward. It’ll be hell getting him back up, and he needs to keep his juices flowing.”

Though I have tossed male chicks into the pigpen like popcorn snacks, though I can ignore the squealing as I extricate the little bitty testicles of little bitty piglets, and though I absolutely do not want the one-year-old donkey Jack to mount and breed his old mother, Chrysanthemum, I still feel bad when Lola sets Jack’s balls in my open hand. They are as big as my fists, veinous, and coated with white mucus. I forget whether we’re supposed to eat these or bury them.

V.

“Daddy told me you’re pregnant,” my pregnant daughter says on the phone. I’m in my mother’s living room, trying to start a woodstove fire with wet logs. This is the first time Rosie has wanted to talk in weeks. “I can’t believe we’ll be mommies together!”

It is not just black widow spiders that kill their mates. The female praying mantis often bites off the head of the fellow who has just impregnated her, and some snails, too, get so furious they lash out, albeit slowly. In the honeybee population, the male can’t even be trusted to be a member of the hive, and if one should survive the breeding season, he is kicked out in autumn to freeze to death.

“I’m forty-seven, honey,” I say.

For starters, I could say the occurrence of miscarriage in American women my age is over fifty percent, or that the chance of chromosomal abnormality is one in eight. But it would only get her worrying about her own potential complications, so I keep the stats to myself. Instead I say, “Things might not work out the way you hope.”

“I’m sure you’ll be fine. Daddy said you never had any problems with the four of us. And you’re built sturdy. You’re strong, I mean.”

A honeybee queen’s daughters are worker bees, loyally attending to their mother. Unlike human daughters, I think, as my daughter moves on from calling me sturdy to imagining aloud how fun it will be for our children to grow up together. When I was pregnant before, I had a few pregnant friends to go through it with, but my daughter seems to have no such allies. She’s felt alone living out of town with her boyfriend, she now admits, and she’s been scared. She also admits she is losing rather than gaining weight going into her fifth month—but it’s okay, she insists, because she was overweight to begin with. She refuses to go to what she and the boyfriend call a Western doctor.

In the honeybee hive, a queen is not inclined to fuss over her daughters. She is drunk on royal jelly, lost in a fog as she pushes out egg after egg, fertilized by the six million sperm she’s been storing in her spermatheca since the day she lost her virginity. No honeybee daughter can hope for indulgence. And yet, who makes that mind-numbing jelly? Who feeds it to her from their own mandibles and proboscises? The only goal for those daughters and their mother is reproduction.

At a certain age, the queen bee is past her prime, and there’s no denying it. Her wing edges fray, her branched hairs lose their sensitivity, her many leg joints ache, and her pheromones grow faint. She no longer has the strength to push out one more blessed egg. At this time of supersedure a daughter must be groomed for the job, stuffed with royal jelly, and sent out to collect new sperm. If all goes well, her sisters will dance around her and hail the new queen.

And if the old queen doesn’t pass the torch graciously, the same daughters who fed her, groomed her antennae, and massaged her sore birthing muscles will cluster around her to radiate an unbearable heat that will kill her. You might find her desiccated body on the ground under the hive. It’s a wise queen who retires willingly, who doesn’t cling to that old joy and pain.

When I get home from the women’s clinic, I find Julianna on the couch beside Nana, reading a book about horses. Seeing me, Julianna turns the book upside down and smiles, seems to know I’m feeling shattery and a little weak, and I sit beside her to tell her a story. Alex has fallen asleep on the floor of the closet in which he sometimes hides out with a flashlight. My mother said he opened and closed the door for about an hour and demanded to know where I was. “And where were you, by the way?” she asks.

As soon as the kids are packed up and sent home with their mother, I head up to the henhouse with a stack of quizzes I have to grade for tomorrow and find the broody hen no longer sitting on her nest. For days I’ve suspected she’s been up and around way too often to hatch anything. I lay my open hand across the dozen small cream-colored eggs—they’re cold. On this day, nineteen of twenty-one, she’s made it clear she’s rejoining the flock.

“You poor thing,” I tell her. She looks so naked without her breast feathers—I wish I could fashion her a sweater vest. I grab hold of her at the feed dish and then sit cross-legged in the straw, where there’s less poop, and hold her on my lap and pet her. “You had it easy, though. You just had to get up and walk away.”

The Silkie is not inclined to snuggle. She makes a purring sound and claws at me until I let her go. She picks her way back to the food, her gray head feathers bouncing.

I’m starting to get hungry, but, more than that, I’m feeling hungry to feed my pregnant daughter. She always loved banana bread with walnuts, and I’m wondering if I can change the recipe, substitute vegetable oil for the butter. But how will it taste? And how will the whole thing hang together without eggs?

I take my phone out of my jacket pocket and hug my knees as I text my husband, who is probably just getting ready to leave his office: I’m in the henhouse if you want to talk. I’ll wait for you here.

I haven’t decided yet what I’ll tell him. I wish I had it in me to lie and say I miscarried. Maybe that would be easier for all of us to live with. I look up at the cobwebs hanging from the ceiling. They are astounding creations, falling upon themselves like layers of ghostly theater curtains, thick with dust, smoky-looking, almost completely obscuring the roof joists. My husband’s so tall he’ll get them in his hair. When he shows up, I’ll skip the science and move right into telling him a story about the magical powers of cobs, mysterious beings who enter the coop at night and whisper stories to the hens. If he gets the webs tangled in his hair, I’ll motion for him to bend down, and if he brings his face close to mine, I’ll brush them away.

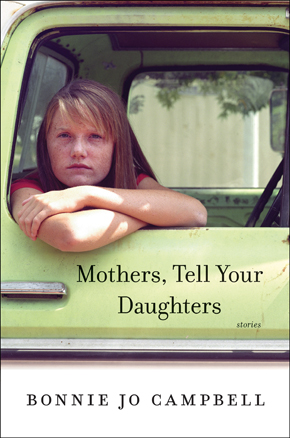

Bonnie Jo Campbell is the author of “Mothers, Tell Your Daughters” (W. W. Norton and Company). Her collection “Women and Other Animals” won the AWP prize for short fiction. Her critically-acclaimed short fiction collection “American Salvage” was a finalist for the 2009 National Book Award in Fiction. She now lives with her husband and other animals outside Kalamazoo, and she teaches writing in the low residency program at Pacific University.

Bonnie Jo Campbell is the author of “Mothers, Tell Your Daughters” (W. W. Norton and Company). Her collection “Women and Other Animals” won the AWP prize for short fiction. Her critically-acclaimed short fiction collection “American Salvage” was a finalist for the 2009 National Book Award in Fiction. She now lives with her husband and other animals outside Kalamazoo, and she teaches writing in the low residency program at Pacific University.