Volume no. 9, Issue 1

Injustice Anywhere is a Threat to Justice Everywhere

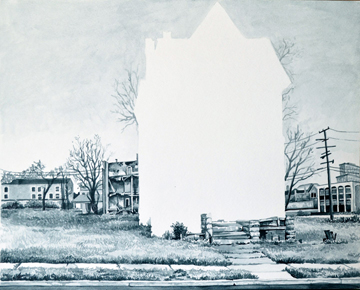

Visual Arts: Suzy González, “Discolored, Misshapen, Broken”

▱

When he stood next to the others, praying or listening to surehs recited from the Qur’an, a glimmer of doubt shone into the darkness of his thoughts. If god existed, why was there so much injustice, inequality, suffering in the world? Why did god enable someone to drop a missile over the shrine and kill my parents while they were paying homage to an Imam? Sometimes he tried to reason the way some of the other members did. ‘Allah’s will is beyond the understanding of us mortals.’ Still, he went on doubting. He prayed without conviction. At times, he skipped it.

Fiction: Nahid Rachlin, “The Wrong Man”

▱

Stones point at me and scream

NAME US HIS TELL, Including you. him

the You. Impossible that you see

Yourself in mirrors. But Monster

Gay Am I. The bottle in the bottle. Something

In this shifted end is this shifted

end of Sublimation. Is not thing A:

—There was a violence. Else’s someone

Words. projecting me

You’re the patriarchy on. Oh! She says,

It’s a light gassing! Easy. A drops jaw. It I meant

Have Possibly Couldn’t. Leverage

The timeline replicates. Rest fiction=Oh!

She says, Appointing customers to days

Of trouble. This is production

For crisis. Queer mafia

Can’t leverage production of quality

Thought because grouping demonstrates

Labeling. Bye.

Poetry: Maura Pellettieri, “Backyard” & 2 more

▱

Visual Arts: Elizabeth Schwaiger, “Pool Crowd” and Other Paintings

▱

Iya Simi also wanted things. She wanted to buy the same kinds of lace that Iya Tope and Iya Fola bought all the time. She wanted someone to hold her at night. She wanted to someone to touch her, and tell her she was beautiful, and they loved her. She wanted to be driven around so she wouldn’t have to walk all day in the heat and humidity of Lagos.

Flash: Deaduramilade Tawak, “Wanting”

▱

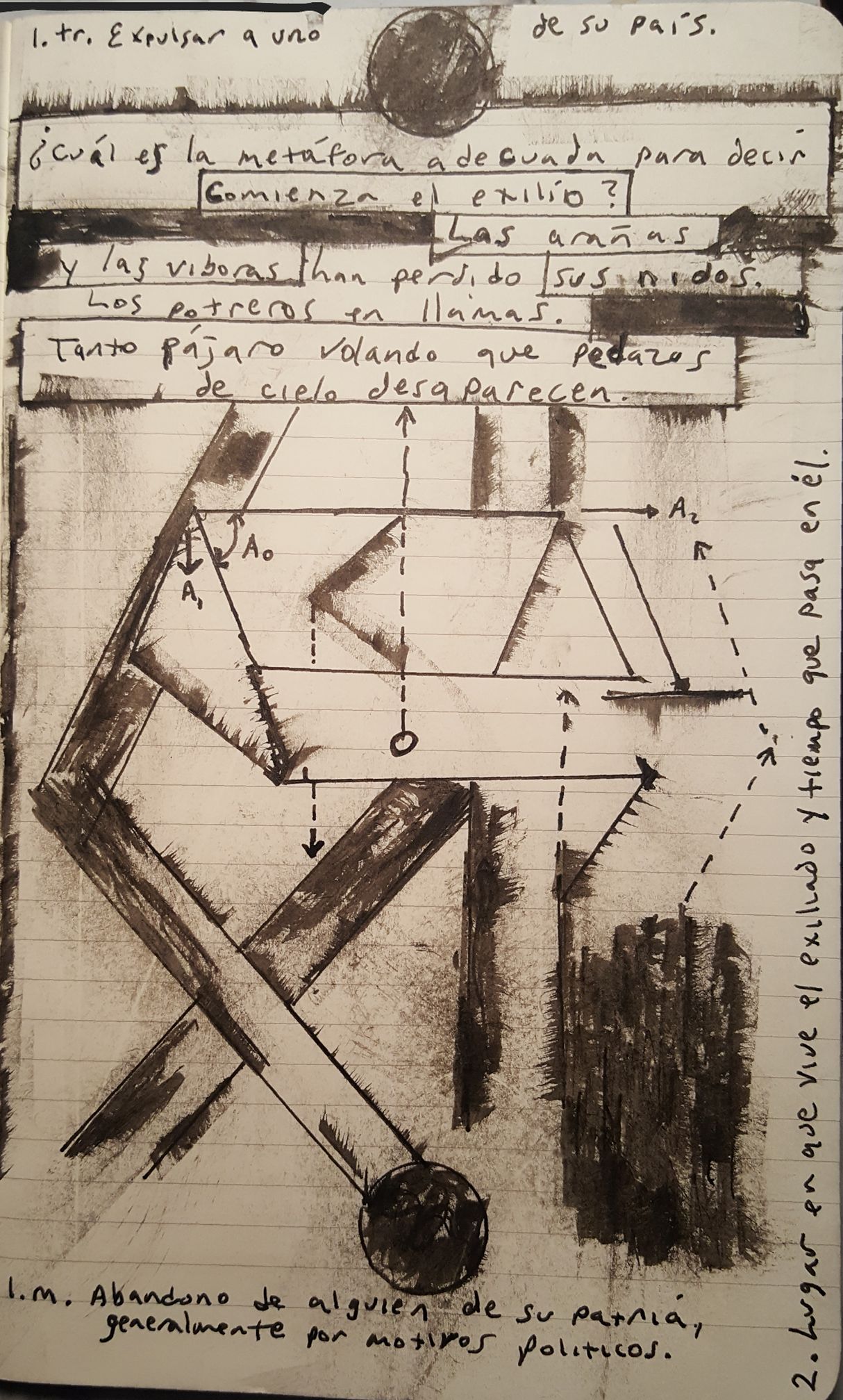

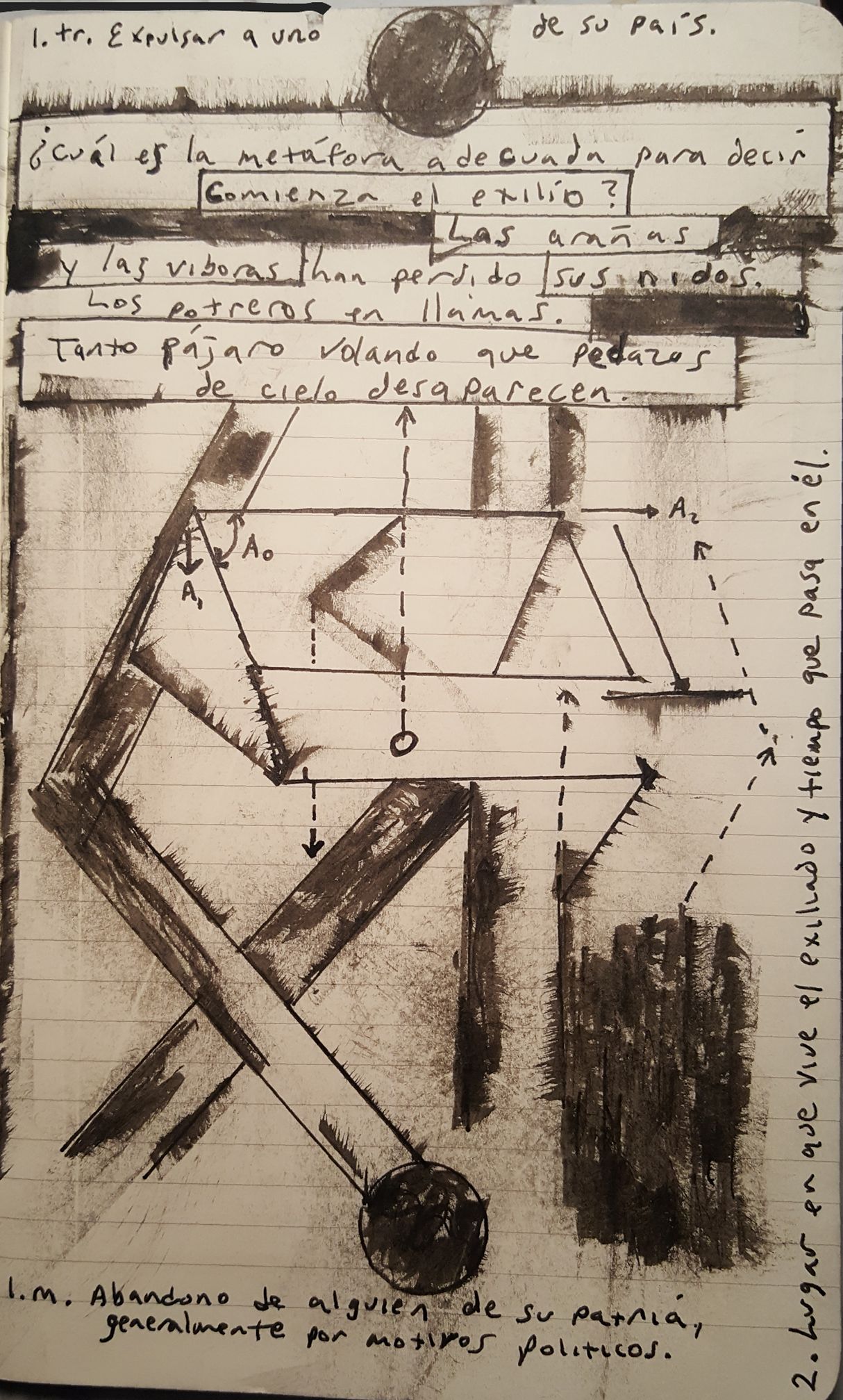

Poetry: Octavio Quintanilla, “Draft 39” & 3 more

▱

Caro Wes,

non sono le palette cromatiche studiate con l’aiuto degli astrofisici di Pantone, nemmeno sono le musichette indie, i vestiti hipster, gli amori puri, le vite avventurose. È la simmetria, l’angolo perfetto davanti alla telecamera. È il mondo geometrico dove tutti vanno da qualche parte, trovano le cose e queste cose hanno un senso, oppure non trovano le cose e non trovarle ha un senso, e si vaga confusi ma sempre dritti e così dopo un po’ la confusione sparisce grazie, appunto, alla simmetria.

È l’ordine, Wes, e la sua mancanza mi costringe a mettere in pausa il dvd, perché fuori dal film quando si piange è un gran casino, e nessuno ti viene a baciare sulla bocca o sulla fronte, e nessuno ha mai il coraggio di rasarsi a zero barba e capelli sottolineando chiaramente il cambiamento in atto, o di lasciarsi dietro sulla banchina un set di valigie Louis Vuitton. Fuori dal film sottintendiamo un sacco di cose, e non bruciamo mai le foto o i diari o i quaderni così da andare avanti una volta e per sempre.

Tua,

M.

Translation: Marianna Crasto, “Fuori dal film”

Dear Wes,

It’s not the color palettes, perfected with the aid of Pantone astrophysicists, or even the indie soundtracks, hipster clothes, pure loves or adventurous lives. It’s the symmetry, the perfect angle in front of the camera. It’s the geometric world where everyone is going somewhere, they find things and those things have meaning, or they don’t find things and not finding them has meaning, and you wander around confused but always straight ahead and so after a bit the confusion disappears, thanks to that very symmetry.

It’s the order, Wes, and the lack of it forces me to pause the DVD, because outside of the movies when you cry it’s a big mess, and no one comes to kiss you on the mouth or the forehead, and no one ever has the courage to shave their beard and hair down to zero to clearly underline the change taking place, or to leave a set of Louis Vuitton suitcases behind on the railway platform. Outside of the movies we leave a lot of things implied, and we never burn photos or diaries or notebooks so as to move on once and for all.

Yours,

M.

Translation: Tim Cummins, “Outside of the Movies”

▱

Interview: Hilary Zaid

▱

Now, this guy’s no Magwitch, he’s got no repentance likely in his future. But he feeds her the Magwitch line, ‘tell anybody what you seen and I’ll kill you,’ and Muriel, shaking, goes in for it. She won’t say a word.

Flash: Elizabeth O’Brien, “Muriel”

▱

And as for me, I have been left behind before, and that’s all it takes to know what those little Texas flags mean, that white star.

Poetry: Benjamin Garcia, “To the Unborn Sibling”

▱

Life wears on our most Zen intentions. All those particulars that are the lifeblood of ode and elegy, all those granular details encrusted with human affection and conflicting desires, fuel the intimate and sometimes exuberant poems in Jeffrey Bean’s latest collection.

Review: Jeffrey Bean, “Woman Putting on Pearls”

▱

Ang sex ay dagli.

Sa katapusan,

isang nakasarang pinto,

isang hubad

na tala.

Translation: Mesándel Virtusio Arguelles, “Q” & 2 more

Sex is a vignette.

Post-coitus,

a shut door,

an open

letter.

Translation: Kristine Muslim, “Q” & 2 more

▱

I remember the decades-old Calvin and Hobbes mug—the one that even survived the house fire that took nearly everything else. You flung it off the porch and into the weeds, and I remember the irate look on your face as I calmly rose from my rocking chair, walked to the mug, dropped to my knees, and pulled it out of the weeds. I laughed as I held it up and theatrically showed you the cup of dirt you’d created, as if I were a magician parading my next great feat. A worm wriggled around in it and everything. I wanted to bring it up to you, laugh as I shoved the mug between your lips and made you drink down the coffeemud, maybe force you to choke on the worm. I wanted to laugh as the worm tickled your gums and wriggled in your teeth. I wanted to laugh as you cried as you’ve made me cry when I’ve felt so helpless and vulnerable and profoundly unsafe. I wanted to laugh.

Creative Nonfiction: Heather Heckman-McKenna, “Drive”

▱

Visual Arts: Rachael Jablo, “American nightmare/ American dream”

▱

A missionary son reared in Japan, a believer in the Social Gospel, and an active progressive in his university days, Selden initially sympathized with the aims of the student movement. He shared their view that the government was corrupt and marching backward, toward the bad old days that fostered the disaster of the Pacific War. And, like the students, he deemed the American military bases in Japan a malign presence.

But, as student idealism yielded place to violence, and as the struggle degenerated into an intramural competition for power among radical groups, Selden challenged the activists. He declared that the students were misguided. He argued that good motives did not exculpate them from responsibility for harmful results. And, most grievous sin of all in the eyes of the radicals, he counseled moderation.

Consequently, despite expressed sympathy for the broader aims of the movement, Selden became a target of the hard-core leftists. Harassing phone calls made sleep difficult; he lectured to near-empty classrooms (his students yielding to threats); and, finally, he was completely locked out of the campus during a four-month student strike. In the end, he gave up—he retired.

Fiction: Lawrence F. Farrar, “We Are The Ones”

▱

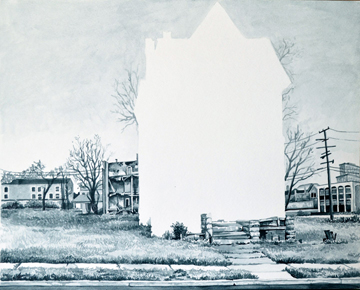

With sections titled after Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Tokyo, and Fukushima, Mariko Nagai could easily rely on the gravity of its subject matter to bind the book. But it is bound with something else, something I don’t know how to name, which results in a silhouette not of simple horror but of the past’s uncanny jut into spaces in which it has been nominally dealt with, grasped, and thereby erased.

Review: Mariko Nagai, “Irradiated Cities”

▱

On the hill, a fierce gust of wind hit the lynx. It wavered back and forth before falling over. The position it fell in made it invisible to anyone looking for it, but its eyes remained open, staring up into the sky until the snow covered them.

Fiction: William Falo, “The Lynx”

▱

On a breathless September night a beggar appears. He lowers himself to the pavement not far from the churro stand. The churro vendor hardly notices him until, holding a cup out to passersby, he intones, “Los santos en la iglesia son cosas del diablo! Los dios antiguos mejicanos son los verdados!” The old man repeats this like an impassioned rosary, holding the cup out as if its truth is sure to win him alms. Some ignore him or shake their heads and keep walking. Others stop. They stand, staring down at him as if something must be done. A woman in high heels steps forward, bends over, and spits into the cup. The old man doesn’t react. She goes on her way. Someone applauds.

Flash: Mark Howard, “A Bridge in Tijuana”

▱

Visual Arts: Whitney Sage, “Homesickness” & “Composition in D”

▱

My mother laughed in that nervous way she had. Then she clenched her jaw and wiped away a tear. I didn’t think it was a laugh tear. I looked for a reaction from my father: none. My uncle: adoring smile, sip of beer, cheer at TV.

Flash: Krystal Powers, “Pineapple Moon”

▱

people will forget you if

you don’t look in their face

Poetry: Amy Beeder, “[border] If the line of uncertainty starts at the wrong side of the hand”

▱

Interview: C. Morgan Babst

▱

– Я не знаю, яке море. На що воно схоже? Знаю тільки, як виглядають літери написаного слова, але коли пускаєш сувій з рук, він сам згортається, слово зникає і жодного моря уже немає.

– Якщо тобі хтось скаже, що море – це велика вода, не вір йому. Море – це насправді чарівне скло, як збільшує все, що ти маєш. Якщо прийдеш до нього з печаллю, вона виросте в ціле горе, поки пливеш, а якщо є в тебе радість – її стане, щоб зробити серед моря острів. Твій друг стане братом і батьком водночас, твій ворог розітне тобі горло і виллє твою кров у воду, з маленького сумніву ти виростиш за пазухою демона, поки пливеш. Мій сокіл теж ніколи не бачив моря. Я вигодував його вже у цих землях. Але ви побачите, я вам покажу. Я повезу вас далеко, в те прегарне місто, покажу вам море, а вас – царю і царевичам.

Translation: Kateryna Kalytko, “Вода”

‘I can’t imagine a sea. What does it look like? I only know how letters of the written word for ‘sea’ look like, but when you let the scroll go it rolls up, the word disappears and there is no sea anymore.’

‘If someone tells you that a sea is a vast water, don’t believe them. A sea is a magic glass that magnifies everything you have. If you bring your sorrow to it, your sorrow would turn into pain while you are at sea. If you have joy, you would get enough of it for an entire island. Your friend would become your brother and your father at the same time; your enemy would cut your throat and spill your blood into the water. From a small doubt, you would grow a demon in your bosom, while at sea. My falcon has never seen a sea either. I fed it by hand on this land. But you will see it, I will show you. I will take you far away, to that beautiful city, I will show the sea to you, and you—to the king and the princes.’

Translation: Oleksandra Gordynchuk, “Water”

▱

I also fear Mr. Chazelle’s answer to his own rhetorical question would be, ‘Who cares if you’re either when the laurels keep coming,’ for which reason I’m astonished at his soulless film’s universal acclaim.

Review: Damien Chazelle, “La La Land”

▱

The phrase ‘losing it’ began to be commonly used in the 1990s. When researching the phrase, I come across an English-language-learners website where a new English speaker titles their post, ‘Am I losing it?’ and asks, ‘Could you please tell me the best meaning for this sentence? By the way, should I just use it when I’m talking with my friends and family?’ Two people reply to say the phrase means getting angry or losing composure. One woman from England adds that it also means ‘losing one’s marbles,’ or sometimes, ‘losing the plot.’

Creative Nonfiction: Beth Peterson, “Lost: An Inventory”

▱

In the winters since, we’ve had seasons of great snow, drifts that stretch from the lake basins to the quarry, dulling each field into identical whiteness. I am busy in these times, salting the roads and waking with the onset of each snowstorm, always in the early dark hours when I pull my boots on with my eyes still shut and stumble into the blank dawn to clear the roads as they fill. It is then, most often, that I think of Ruby—or more truthful to say it is then that I think more of him, since there is no breath alive for me anymore without his name in my mouth.

Beyond those moments, though: into the night and streaking across the north country where in our lakes sharp-toothed fish slug in the deep; beyond hunting stands soaked in venison blood; beyond the edges of a map, gray fogged: I push my imagination forward as he did, swimming into the world unknown. Beyond my body. Beyond and into desire.

Fiction: Bridget Apfeld, “Holocene”