Crossing

By Hisham Bustani

Translated from the Arabic by Maia Tabet

1–First Attempt

You cross the bridge suspended over the canal. Colored ships slowly glide across the surface of blue waters below. Now and then, from beyond the hills of fine sand, a date palm emerges, a village, some people. Fish dart across the lake and a swarthy, dusty child poses for the camera, stick in hand.

§

Eight people on their way to Gaza: the road is long and strewn with checkpoints.1

“Salamu alaikum,” and we go through the second checkpoint; at the third, nobody’s there. And at the fourth, a policeman waves us on. Just like that.

The sun is warm and everything is coming together, it seems. Yesterday, rumor had it that the crossing would be open between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. It was only a rumor, but oh, the hope that tickled their minds: They would get through.

§

Old beat-up buses and cars stood under the dilapidated bridge. The green Mercedes whisked them off before they could reach the bus, and now they were lurching through the chaos of Cairo traffic.

‘A’ed would not desist. Tracking them from the front, from the back, from above, from below, as they try to dodge the large lens of his camera. The pressure gets under their skin, making them tense and uneasy: Who likes being under constant surveillance?

In the backseat is the guy with the explosive name: Nasrallah, God’s victory. The very antithesis of nasr Allah—but like his paintings, he’s as calm as a puff of clouds. In the front is Yusif, now clean-shaven as every groom must be when processing toward his bride. Kamal, for his part, dreams simultaneously of music and of the building site. At every checkpoint, al-Jaabari mumbles, “Lo, we fixed before them a barrier and behind them a barrier,”2 and Kawthar smiles, watching the pavement racing by below. We did it! We’re on our way there, for real this time. Oh, but will the journey ever end?

§

When the ambassador asked why they didn’t take the Karm Abu Salem crossing, Yahya had exploded. “You expect us to get an Israeli stamp? Look, Mr. Ambassador, all we’re asking for is a simple but official letter to facilitate our passage. It’s just a formality. It’s not as if it is binding on the embassy or the Egyptian authorities in any way. It’s a stupid piece of paper that might help us get around some of the piles of metal strewn along the way.”

“Listen, son, whether you end up in heaven or hell, the road passes by death. Regardless of whether Gaza is your paradise or your inferno, the road there doesn’t pass by me. Go die somewhere else.”

§

Hisham Pasha. Ibrahim Beyk. So many soldiers, their faces fixed in jaundiced smiles. We can’t let you in for your own safety. You’re in our custody, and this is a war zone. Standing in the open air, their faces were whipped by cold gusts of wind. Neither pleading nor the unsweetened coffee worked any magic at the Kharrouba checkpoint. We had slipped through all the others as if by magic, but not this one.

Had they hidden the camera properly … and had the blond guy not sat by the passenger window … and had (fill in the blanks) … Something about them screamed that they were a mass of anger wrapped in love. It was inevitable they would be stopped. And they were.

Back they went.

§

“We care for your safety more than for our own citizens’. This is a war zone. Many of our men have been killed here. That’s why we can’t let you through.” So said a plainclothes lieutenant, the highest security official at Kharrouba, the only checkpoint to have stopped us in the long succession beginning with the one right outside Cairo and ending at Checkpoint Impossible: Rafah.

“We’re not sure how you managed to get through the earlier checkpoints … You must be ghosts or something. Unfortunately, luck has brought you this far where even ghosts can’t get through.”

Luck had nothing to do with it, not even remotely: The road to Rafah is a straight shot—a long series of checkpoints with tarmac in between. And Kharrouba was the endpoint of the four-and-a-half hour journey that began in a sand-swept place under a Cairo bridge. The sand would be our faithful companion the entire way.

The Marj terminal swarmed with public transport buses and vehicles. Sa’eed, the driver of the eight-passenger green Mercedes, had asked for 400 Egyptian pounds. As one of us thought this was a steal, we agreed to the price, and when we got to our destination, we gave him 450 pounds, including the obligatory tip—the man had endured our two-hour-long argument with security officials, as well as the cold desert night and the lieutenant’s petty humiliations. Along the way, two of us (not knowing the other had done the same) offered him another 10 pounds to compensate him for the sum that was the object of a veritable storm of phone calls between Abu Shayma’, the garage conductor, and Sa’eed. The other drivers had jumped into the fray and cautioned Sa’eed not to act recklessly when his voice trembled in protest against the controller’s levy on each vehicle. “I swear to God, Audeh, he’s only supposed to stamp my vehicle’s card, but what can I do? I’m the one that does all the work, and he gets a share of the cake!”

Audeh was what Sa’eed called whoever was being friendly toward him, even if the lucky candidate got screwed in the process: In our case, not only was the regular fare for that trip 230 pounds, but in his eagerness to part us with our money, the next day Sa’eed got an extra 100 pounds, just to take us from El-Arish to Rafah. “A special price, I swear, just for you, ya Audeh, because I really like you,” he explained—the regular fare for that trip being 40 pounds.

“No sweat, think of it as wealth redistribution,” I said as we stopped halfway between El-Arish and Rafah where there was another attempt to send us packing.

“You don’t have the required permit from your embassy. I’m sorry, there’s nothing I can do for you. We’ll notify the local command post and wait for instructions.” So we waited, steeped in cigarette smoke, unsweetened coffee, and small talk. To the security men, we were like foundlings, a bunch of writers and artists eager to discuss any topic under the sun in the tedium of their no-man’s-land. The encounter was warm in spite of the no-go order.

“Too bad, you were turned down. Try again tomorrow.”

Even though tomorrow is an eternity to those who wait, we went back to El-Arish, hopeful.

§

There’s a white surveillance balloon and three jets scarifying the face of the sky. Soundlessly, a plume of black smoke rises to the right and then another in the middle: ahead, just smoke, and then there she is. A mere arm’s length away—no further than a heartbeat or the enveloping smell—lying before your very eyes, the beloved, her hair unfurled along the edge of the shore, white foam lapping against her bare thighs.

Stretch out your hand and you can almost touch her, but before you can feel the shiver of the thrill, walls and barriers go up, and you go down to the ground in the swarm of soldiers. No Entry, No Photography, No Sitting, No Standing, No Loitering, No Return—and you, a mere cockroach squirming under the avalanche of shoes to your head.

They scattered, trying to conceal themselves amongst the fair-skinned people, some Frenchmen, so as to slip through the metal bars like the desert dust. But even the all-white French breeze couldn’t get by the watchful concrete towers of the so-called Rafah Land Port.

§

The border. The line that separates here and (t)here. The line between who we were and who we are: passage, wilderness, dispossession.

Slithering like a snake across the tarmac, the sand seeps under our feet and through the barriers where we stand looking for a chink in the phalanx of security men. And Palestine, right there, only meters away. Sand on sand, the sand where they dwell, the very same on which you step. And yet, here it’s Egypt and there it’s Palestine. Here, we stand pacing, and there, it might as well be another galaxy, forbidden like the fruit of the tree of knowledge. And you, tinier than a grain of sand blown by the wind between the metal barriers.

It’s for your own safety. You don’t have a permit from your embassy. You’re Jordanians, what’ve you got to do with Gaza? That afternoon, Israeli jets weren’t the only ones striking. And they weren’t there to surrender to any bombardment. They were there, with all their gear, their ‘oud, their voices, and people all around. Like the fingers of a hand curling into a fist, they gathered around, and broke into song.

We will not lie down and die. Nor will we allow those on the inside to die. Even in death, theirs is an act of not dying. These barriers/crossing-points will not break our bonds: Over there, they remain, be it hollering at the top of their lungs from one flank of the Golan to the other, making their way across the river Jordan, or cleaving the waves on ancient vessels. And we, over here, stand at the crossing with all our sadness.

We shall cross.

2–Mohammad Hamad al-Hunayti

The funeral was a solemn affair. A procession of mourners, Arab delegations, tribal chiefs, and the king himself followed behind the casket mounted on a gun carriage and led by phalanxes of rebels—titans draped in cartridge belts, their shoulder-mounted rifles swinging to the rhythm of their vigorous steps.

Under the blanket of the sky, their ‘abayas spread out on the ground in front of Mohammad al-Hunayti’s house on the flank of Jabal al-Lweibdeh, hundreds of mourners awaited the arrival of the casket from Haifa. Salvos of gunfire erupted as soon as it came into view, making it way down the road from Salt. The martyr had returned: it was a day worthy of the Last Judgment.

<

Abdelhalim al-Nimer and the men of Salt had insisted that the martyr remain in their midst two more days. “The man is our son,” they had cried. How dear they held him, cherished as the apple of an eye, and they accompanied him all the way to Amman.

§

Every night, the German shepherd stands on the perimeter wall of the house in Abu ‘Alanda looking out to the west. The dog, which Mohammad al-Hamad had brought back from Haifa on his last trip, begins to howl, crying bitter, heart-wrenching tears.

“Kill the dog. Mohammad will never return.” So said the mukhtar of the al-Hunayti clan, Abu Khaled, through clenched teeth.

§

The shortest route follows a straight line, and that is how they proceeded along the coastal road. Bound for Haifa, they had set off from Beirut in a procession of vehicles laden with weapons, including two trucks piled with explosives.

The British officer at Ras al-Naqura sent word of their arrival, and when they got to Acre, the inhabitants warned him: “Mohammad Beyk, the Zionists may have gotten wind of your convoy. There is news that they tried to ambush you in Ain Sara near Nahariyya and failed. The coastal road will be your undoing. Forget this route and go back to Beirut. From there, you can go to Damascus and then onto Irbid and Haifa. It’ll take three days, but it will save your life.” Others suggested that he ship the weapons by sea, or at the very least, stay with them overnight in Acre.

“The safest route may take three days, and the churning of the sea is never without a wave,” Mohammad Beyk replied. “But I left Haifa alone on her balcony waiting for the seafarer who only days ago crossed rivers of tarmac toward the north. The seafarer’s beloved never sleeps, and she doesn’t like waiting,” he added. “Ya ikhwan, Haifa is without arms. Those marauders will not wait. If they lay their hands on Haifa, it will kill me just the same. Let me die in her bosom trying to defend her rather than watch her being overrun from afar.” He left for the South and never looked back.

§

He was shrewd, smart, and educated, and the slightly disfigured Englishman had been doing the rounds of the tribes to enlist their sons into his army.

Mohammad al-Hunayti was the son of the region’s ruling pasha under the Ottomans—a man who’d been the terror of the bandits and thieves that were the Turkish army’s foot soldiers. His mother was a Kurdish Damascene who insisted he get an education and sent him to study under a Circassian tutor at the entrance to the Great Mosque in Amman. Muhammad was never to be found sleeping without a book across his face. His eyes sparkled with intelligence as he debated and argued, and Glubb Pasha recruited him forthwith. He was quick to prove his military acumen and was appointed an officer in Haifa.

As it behooved any intelligent young man whose brain the British and the Zionists drilled into day in and day out, the officer siphoned the weapons that fell into his hands to the city’s inhabitants. Later, he assembled his men and addressed them as follows: “At night, slip off your military uniforms, dress in civvies, and go train the people of Haifa in warfare.” And so it was.

Since it behooves a military field commander to know his enemy and understand what is required of him to mete out defeat, he wove bonds of blood with his comrades in arms among the rebels. The handsome Bedouin met with all the local leaders—Rashid al-Hajj Ibrahim, Suroor Barham, al-Abed al-Khatib, Abu Nimer, Mohammad Abu Aziz, Abu Ali Dalloul, Hassan Shiblaq, Abu Ibrahim Odeh, Rashed al-Zafari, Nimer al-Mansour, Jameel Bakeer, and Yousef al-Hayek—and he became one of them.

Did I say became? That is false, because he had been one of them ever since screaming his way into the world at the desert’s edge. And they were of him from the time he had drawn his first breath.

“You are Jordanian, Mohammad Beyk, what have you got to do with the Palestinians?” Glubb had asked, waving his spies’ reports in the air.

“Ya basha,” Mohammad had replied, “you are the ones who drew the boundaries of this land. Before you, there was neither Palestine nor Jordan, neither Syria nor Lebanon. Until you came along, we traded in the souks of Damascus and wintered on the shores of the Mediterranean. Defending Haifa is defending my village, Abu ‘Alanda, ya basha. Here, take these insignia of yours. I have no use for them anymore. The freedom fighter’s badge is far superior.”

Rifle slung on his shoulder, and cartridge belts draped across his chest, he came back from that confrontation and took off his military uniform. He donned the rebels’ garb and became the high commander of harakat al-jihad al-muqaddas (the Sacred Jihad Movement) for the Haifa district. After that day, no one would ever trample him underfoot nor would he ever lower his head again, were it to receive the crown of a monarch.

How many a king, unjust, tyrannical, and headstrong

His garments forever dragging on the ground

His bones no more than the dust of rusted metal

Trampled underfoot by all.3

After that day, no one ever trampled him underfoot: He unified the city’s defenders under his command and deployed the small army of 350 combatants across 10 different sectors, each with a commander of its own. Its head resting in the lap of the Mediterranean and within reach of the Gulf’s embrace, mild and gentle Haifa turned into a saber-toothed, bare-clawed tigress, and the men who had issued from her womb would not disavow her, whose bosom had nursed them.

§

Motorcycles shot by like lightningbolts, followed soon after by barrels rolling down the road towards them in a hail of gunfire and hand grenades. Mohammad al-Hunayti instructed his chauffeur to proceed, and the driver of the first truck followed suit, but the barrage of fire was so intense that there was a skirmish.

The last truck in the convoy turned around and headed back to Acre. The rebels ran towards their leader who was lying on the ground cradling his rifle. Dodging bullets and rolling in the little craters formed by their impact, Suroor Barham crawled on his belly to reach him. “Mohammad Beyk …” he said, shaking him roughly, “answer me, brother …” But Mohammad spoke not a word and, as never before, remained completely still. A trickle of blood no thicker than a thread issued from between his lips. Mohammad al-Hunayti had returned to Haifa.

From the corner of his eye, Suroor could see the Palmach fighters clambering up the truck and neutralizing it. He felt around his pocket and located it. “Beloved, today is the day of our betrothal …” he said, pulling out the pin and running. Red gouges appeared on his back, and little dart-like pins ripped his entrails, but a light hand carried him, as if the two feet propelling him were not his own. He reached the truck and exploded.

The inhabitants of northern Palestine and southern Lebanon as far north as Sidon swore that on the evening of Wednesday March 17, 1948, the earth had trembled below their feet, that their houses had shaken, and that a man had been seen flying through the air4 and landing on top of one of the railcars going towards Acre.

§

“Hey, Abdel-Razzak … Abdel-Razzak,” screamed a child outside the door, “your father’s picture is in all the papers. He fell in battle.” The headline, “Martyr who Stunned the Zionists,” in red lettering, took up the entire front page of al-Difaa’. “On their airwaves,” the report said, “they described him as a menace unlike any other Arab commander.” In a traditional gesture of grief, his mother, Umm Mohammad, upended the coffeepots on the ground, and ululations filled the air.

When they uncovered the body before his relatives, his face looked just as it did in the photograph hanging on the wall. If anything, it was more radiant. There were some who said they could smell the aroma of oranges exuding from his body.

Nothing in him was altered other than a line of bullet holes on his chest. “A true hero, my child, you never gave them your back.” His mother kissed his forehead, and the funeral procession set out.

Right behind the casket marched rows of titans draped in cartridge belts, shoulder-mounted rifles moving to the rhythm of their vigorous steps, a child weaving between their legs and tripping over their feet. One of them pushed him roughly. “Go play elsewhere,” he yelled.

“Don’t push me away, that’s my dad …” protested the child. The man pounded his head with his fists and wept, and then he hoisted the boy up onto his shoulders.

§

Communiqué from Haifa City National Committee

March 19, 1948

Death Notice

Herewith, a convoy of heroes that met their maker in service to the nation. Haifa City National Committee is grieved to announce to our honorable Arab umma the death of its brightest and dearest sons and bravest soldiers, as follows:

1. Mohammad Beyk Hamad al-Hunayti, the fearless commander of the Haifa garrison;

2. Suroor Barham (Abu Mahmoud), deputy commander;

3. Fakhreddine Abdel-Wahed (Egypt);

4. Omar Khaled al-Khateeb;

5. Ahmad Khader Musa;

6. Ahmad Wajeeh Rahhal;

7. Yusif al-Taweel;

8. Ali Kabbar;

9. Hassan Salameh (Jordan);

10. ‘Atallah Salameh (Jordan);

11. Ali Shujaa’;

12. Mohammad Mustafa Khalil;

13. Albert the Armenian.

They fell on the battlefield following an ambush at around three o’clock on the afternoon of March 17, 1948.

We mourn these heroes of the Arab nation in the knowledge that the blood they have shed will never be forgotten.

§

Chronology

March 17, 1948: death in battle of the leader of the armed resistance in Haifa, Mohammad Hamad al-Hunayti, and his deputy, Suroor Barham, following an ambush by the Zionist Palmach forces on a convoy of weapons under their command.

April 6-8, 1948: failure of the attack on Kibbutz Mishmar HaEmek, on the Haifa-Jenin road, by the forces of Jaysh al-Inqadh (the pan-Arab volunteer force) under the command of Fawzi al-Qawuqji. Zionist forces carry out a counterattack in which they are able to cut off scores of Arab villages as well as the outlying areas of Haifa.

April 8, 1948: Death of commander Abd al-Qader al-Husseini in the battle of al-Qastal, and fall of the village.

April 9, 1948: Massacre of Deir Yassin.

April 22, 1948: Fall of Haifa to the Haganah.

May 14, 1948: David Ben- Gurion proclaims the establishment of the State of Israel.

3–Second Attempt

Between the grim concrete wall and the fields of red poppies, where a thin line separates life and death, old, cracked fingers dug through the soil, clinging to the edges of the ground like claws. From under them rose a body, tall and lofty as a mountain, its two arms, straight as rifles poised to fire, legs like columns carved from the rocks of the lilac hills, a face like a city by the shore keeping vigil for her seafaring lover.

Mohammad Hamad al-Hunayti dusted himself off. Looking around, he found numerous people staring at him, mouths agape.

“Who are you?” his warm voice exclaimed.

“We are the blood that has stopped flowing after misery-induced strokes blocked our arteries,” said the injured man.

“We are the tree branches that have extended to the neighbor’s house, which the neighbor cut and stacked to dry behind the wall,” said the mother.

“We are the ones who may not be visited or embraced because they say that we are not who we are,” said the organizer of the delegation trying to cross.

Is that what we have come to? I’ve been gone only sixty-two years and this is what it has come to, Mohammad Hamad al-Hunayti thought to himself, but when he screamed, all that came out was a roar. As the many fingers emerged from the soil, towering bodies split the earth, dusted themselves off, looked around, and embraced each other like long-lost friends:5 Izzedine al-Qassam, Ziad Tanash, Rachel Corrie, Abd al-Qader al-Husseini, Wafa’ Idriss, Firas al-Ajlouni, Faris Odeh, Kayed al-Mufleh al-Obeidat, Dalal al-Mughrabi, Ahmad Abdelaziz, Suroor Barham, Sa’eed al-’Aass, Ahmad al-Majali … “How’s it going? Long time …” “Yeah, really too long.”

As they set off, the earth shakes and with every tremor, hundreds, no, thousands, and then millions emerge, and every language under the sun from every corner of the world also sets forth; with every step, the walls and the roadblocks fall away, and they cross. With every step, the villages and houses are returned, the names and the memories recovered, the weddings and dabkehs come back, and the smell of oranges fills the air.

They all met on the shore of Haifa, all those who had crossed border posts and boundaries, roadblocks and walls, and all those who had come from the sea, sailing on ancient boats. They danced and danced until it was light, until the grass was brought forth and the herb had yielded seed and the fruit trees bore fruit all across the face of the earth, which had been void and formless and covered in darkness. A new day had sprung.

§

The Book of Zechariah, Chapter 156

I have come from east of the river. I sound my roar, the roar of a lion, and then cross. Not by the might of the sword, but with my own two feet. And lo my friends appear; from the soil below they come forth, from the houses they come forth, from every nation of the earth they come forth to walk by my side. The earth shakes under their footsteps, and the walls crack open. Death shall be the lot of those that have slain lives by the sword. And fire shall burn those who unleashed rivers of blood. And the Lord of hosts shall call to his people: I come with fire, with my chariots like a whirlwind, to render my anger with fury and my rebuke with flames of fire. But the earth shakes, and the Lord’s people scatter and run. And the Lord of hosts calls to his people: I have given you a land on which you did not toil and cities you built not, and you dwell in them; of the vineyards and olive groves which you planted not, yet do you eat. Your male and female slaves are to come from the nations around you; from them you may buy slaves. You may also buy of the children of the strangers that live among you and of those of their lineage that are born in your land, who are with you, and they shall be your possession. You may bequeath them to your children after you to inherit as a possession forever. But the earth shakes and the Lord’s people scatter and run. On this day, people shall cross from the four corners of the earth, and that day shall be as the day of the locust, as the tower of Babel. Every tongue shall appear, the kingdom of justice shall be formed, and the kingdom of the sword that benighted every nation shall lie in ruins and perish.

4–Discarded Photo Album

___________________________________________________

Notes

1 News brief: “A delegation of Jordanian writers and artists was prevented from entering Gaza through the Egyptian Rafah crossing on 2/17/2009. The delegation, calling itself Jordanian Intellectuals for Gaza, was part of an international movement to break the siege on the densely-populated strip following Operation Cast Lead, Israel’s massive assault on Gaza. The group, made up of Hisham Bustani (writer), Mohammad Nasrallah (painter), Kamal Khalil (musician), ‘A’ed Nabaa (film director), Abdel-Rahman al-Jaabari (caricaturist), Kawthar ‘Arar (journalist), Yusef Abu-Jaysh (writer), and Yahya Abu Safi (researcher) remained stranded at the Rafah border crossing for three days; there, they staged a protest in solidarity with the people of Gaza, erecting a display of caricatures in front of the crossing. They are expected back in Amman, tomorrow.” Al-Ghad, Feb. 20, 2009.

2 “We fixed before them a barrier …” is Verse 9 of Sura 36, Ya Sin. (The Qur’an: A New Translation by Tarif Khalidi, New York: Viking Press, 2008.)

3 How many a king…: those lines of Nabati verse were composed by Muhammad Hamad al-Hunayti himself.

4 The flying man was Mahmoud Abu Salem of the Khdeir clan (tribe of Bani Sakhr). He was the personal bodyguard of Mohammad al-Hunayti and the sole survivor from the ambush operation. Propelled by the force of the explosion, he landed hundreds of meters away on the roof of a railcar on its way to Acre.

5 Izzedine al-Qassam (b. in 1882 in Jableh, near Latakiyah, in what is now Syria) was condemned to death by the French Mandate authorities in Syria for his anti-colonial resistance activities. He left Jableh, and in 1920, made his way to Haifa where he began to organize armed resistance to the British Mandate authorities and Zionist colonizers in Palestine. He died on the night of November 19, 1935, in a firefight with British soldiers in the pine forests of Ya’bad. He was buried in Balad al-Sheikh, a village southeast of Haifa.

Ziad Tanash, from Howwara near Irbid, Jordan, was a member of the Jordanian Communist Party from an early age. In the mid 1970s, he joined the Lebanon-based Quwwat al-Ansar, the armed wing of the party, fighting Israel. He distinguished himself for his bravery in standing his ground before an Israeli tank. He was killed in 1976 in an Israeli air strike. His friend, the Palestinian poet Izzidin al- Manasra, buried him in Beirut’s Martyrs Cemetery. During the funeral, a woman from the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila pointed to the shrouded body, exclaiming, “Look, his wound is still green” (that is, fresh or raw). Al-Manasra penned the poem, “We shrouded him in green,” in Tanash’s memory, later famously set to music by Marcel Khalife.

Rachel Corrie was a U.S. member of an international solidarity group with Palestine. She was born in 1979 in Olympia, Washington, and was killed by an Israeli D9 Caterpillar bulldozer as she tried to prevent it from demolishing a Palestinian home in Gaza on March 16, 2003.

Abd al-Qader al-Husseini (b. 1910) was the leader of the armed resistance in the Jerusalem district during the 1948 war. He was killed in the battle of al-Qastal, on April 8, 1948.

Wafa’ Idriss was the first female suicide bomber of the al-Aqsa Intifada (2nd Intifada) that began in 2000. One day after Israeli F-16s had strafed the Palestinian cities of Gaza, Tulkarm, and Nablus, she blew herself up in occupied West Jerusalem on January 27, 2002.

Firas al-Ajlouni (b. in Anjara, in Jordan’s northern district of Ajloun) was a Jordanian

air force pilot, who single-handedly faced off an Israeli air force squadron during the 1967 war. He flew and landed his plane multiple times following repeated Israeli air strikes against Jordanian military jets standing on the runway. Against orders, he carried out several strikes deep inside Israeli lines and was killed by Israeli fire the last time he launched into flight on June 5, 1967.

Faris Odeh was the 14-year-old boy killed by Israeli gunfire at the Karni crossing in Gaza on November 8, 2000. A photo of him hurling a stone at an Israeli tank ten days earlier was seen all over the world, becoming an iconic representation of Palestinian resistance to the Israeli occupation. Faris repeatedly told his parents that he dreamt of his deceased cousin, Shadi, urging him to avenge his own death at the hands of Israel.

Kayed al-Mufleh al- Obeidat, aka the Falcon of Palestine, was born in Kufr Soom near Irbid, in what is modern-day northern Jordan. He was killed in 1920 while leading an attack on British forces in the region of Tilal al-Thaa’lib (the fox hills) in what is now Palestine.

Dalal al-Moghrabi (b. 1958 in the Sabra refugee camp, Lebanon) headed Operation Kamal Adwan, named after the Palestinian leader assassinated by Mossad in Beirut in 1973. On March 11, 1978, she and her squad of fedayeen hijacked a bus on the coastal road between Haifa and Tel Aviv, hoisting the Palestinian flag along the highway. A special unit of the Israeli army, led by Ehud Barak (later prime minister), put an end to the operation, killing all the fedayeen involved. One U.S. bystander and thirty-eight Israelis were killed as a result of the operation, and another seventy-one Israelis were wounded.

Ahmad Abdelaziz is Egypt’s national hero from the 1948 war. He was born in 1907 in Khartoum, present-day Sudan, where his father commanded the Egyptian army’s 8th division. Abdelaziz resigned his own military commission to lead the volunteer Egyptian battalion in Palestine, inflicting significant losses on Zionist forces. The Jordanian commander of the 1948 battle for Jerusalem, Abdallah el-Tell, said that in losing Abdelaziz, “the Arab armies had lost their choicest leader.” He is buried north of Bethlehem.

Suroor Barham (b. 1930) was a follower of Izzedine al-Qassam. Along with others, he established the Black Fist, a group opposed to the British Mandate and Zionist colonization in Palestine. He joined the Haifa garrison as Mohammad al-Hunayti’s deputy commander. He was killed on March 17, 1948 in the Palmach ambush of al-Hunayti’s arms convoy.

Sa’eed al-’Aass (b. in Hama, present-day Syria) was a leader of the 1925 Syrian Revolt against the French colonial authorities. He was also active in the anti-British revolt in Palestine and was killed on October 6, 1936, in the hills between Jerusalem and Hebron. He was buried in the village of al-Khader, west of Bethlehem.

Ahmad al-Majali, known as Ahmad Dhaylan al-Majali, was born in 1963 and died in 1983 fighting on the front between Israel and Lebanon. The poet Ibrahim Nasrallah wrote “Love Song to the Martyr of al-Karak” in his memory. The poem was set to music by the Baladna Ensemble under the direction of Kamal Khalil. The Majalis are a prominent family from the governorate of al-Karak in southern Jordan.

6 Chapter 15 of the Book of Zechariah is a fragment of text found in the Qumran Caves along with other texts of the Essene, known as the Qumran Caves Scrolls. It was not canonized in the Hebrew Bible.

العُبُور

هشام البستاني

1- محاولة أولى

تجتازُ الجسر المُعلّق فوق القناة. تمخُرُ ببطء ٍ من تحتك بواخرُ ملوّنةٌ على صفحةِ الماء الزرقاء، ثم تمتدُّ جبالُ الرّمال الناعمة. بين حينٍ وآخر تنبثقُ أشجارُ نخيلٍ وقرىً وناس. ثمَّةَ بحيرةٌ وأسماكٌ تعبُرُها بسرعة، وثمَّةَ طفلٌ أسمرُ مغبَرٌّ يقف مع عصاه الخشبيّة أمام الكاميرا.

§

ثمانيةٌ على الطريقِ إلى غزّة، والطريقُ طويلٌ ومزروعٌ بالحواجز. “سَلامو عَليكو..” وتمرُّ من الحاجزِ الثاني، وعند الثالثِ لا أحد. شُرطيُّ الحاجز الرابع يؤشّر بيدهِ من بعيدٍ أنْ مُرُّوا. ونَمُرُّ.

الشمسُ دافئةٌ وكلّ شيءٍ يتواطؤُ. بالأمسِ سمعوا إشاعة: “غداً سيُفتَحُ المعبرُ بين العاشرةِ صباحاً والرّابعةِ مساءً”. إشاعة. لكنّهُ الأمل. آهٍ من الأملِ يعبثُ بعقولهم: سيعبرون.

§

تحت الجِسرِ المُتهالكِ وقفت باصاتٌ وسيّاراتٌ مُتهالكة. سيارة المرسيدس الخضراء اختطفتهم قبل أن يستقلّوا الباص، وها هُم يتدعثرون في فوضى الزّحامِ القاهريّ.

عائد لا ينفكّ يُلاحقهم بِعَدَسَتِه: من الأمام، من الخلف، من فوق، من تحت، وهم يُحاولون الهُروب، لكنّ ضغط العين الكبيرةِ ينفذُ من تحت جلودهم مُخلّفاً شعوراً متوتّراً من عدم الرّاحة: من يُحبّ أن يكون تحت المراقبة الدائمة؟

في الكُرسيّ الخلفيّ يجلس ذو الاسم المتفجّر: نصر الله، وهو بعكسِ اسمهِ -لكن كلوحاتهِ- هادئٌ كسربِ غيوم. في الأمام يجلس يوسف بعد أن حَلَقَ لِحْيَتَهُ لِيُزَفَّ إليها. كمال يحلمُ بالموسيقى وبورشة البِنَاء معاً. قبل كل حاجز، يتمتم الجعبري: “إجعَلْ أَمامهم سدّاً وخلفهم سدّاً..”، وتبتسم كوثر إذ تُشاهد الأرض تُسرعُ تحتها: لقد فعلناها! نحن حقّاً في الطريق إلى هُناك، لكن هل سينتهي الطريق يوماً؟

§

“لماذا لا تذهبوا من معبر كرم أبو سالم؟” قال السفير بينما انفجر فيه يحيى: “أتريدنا أن نأخذ تأشيرة إسرائيلية؟ إسمع، كلّ ما نريدهُ هو كِتابُ تسهيلِ مرور. مجرّد حبرٍ على ورق، لا يُلْزِمُ السفارة ولا يُلْزِمُ السُّلطات المصرية. مجرّد ورقةٍ لا قيمة لها تزيلُ جزءاً بالألفِ من الكُتل الحديدية المرميّةِ في طريقنا.”

“اسمع يا بُنيّ، الطريقُ إلى الجنّة أو النار يمُرّ بالموت. غزّة هذه قد تكون جَنَّتَكَ أو نارَك، لكن على أيّ حال، طريقُها لا يمُرُّ من عِندي. إذهَبْ ومُتْ في مكانٍ آخر.”

§

هشام باشا وإبراهيم بيه وعسكرٌ كثيرون يبتسمون ابتساماتٍ صفراء. “نحن لا نستطيع إِدخالكم حِرصاً عليكم. أنتم أمانةٌ في رقبتنا وهذه منطقة حرب”، فيما صَفَعَت وجوههم تيّارات الهواء الباردة في الخلاء. لا الدّعاءُ ولا القهوةُ السّادة كان لها مفعول السّحر على حاجز الخرّوبة.

لو أنّنا أخفينا الكاميرا جيّداً، لو لم يجلس الأشقر بجانب الشُبّاك الأيمن للسيّارة، لو… ولو… ولو… لكنّ كلّ ما فيهم كان يصرُخُ رغم ذلك: كتلةٌ من الغضبِ المغلّفةِ بالحبّ، وكان لا بدّ أن يوقَفُوا. وأوقِفوا. وعادوا.

§

“نحن نحرص على سلامتكم أكثر من مواطنينا، هناك في الداخل منطقة حرب، وقتل من رجالنا كثيرون، ولهذا لا يمكن أن نسمح لكم بالمرور”. هكذا قال لنا المُقَدَّم ذو اللباس المدني، أعلى مرجعية أمنية على حاجز الخرّوبة، وهو الحاجز الوحيد الذي أوقفنا من سلسلة طويلة من الحواجز الأمنية التي تبدأ ما أن تخرج من القاهرة، وتنتهي عند الحاجز المستحيل/الحاجز الأخير: معبر رفح.

“لا ندري كيف مررتم من الحواجز السابقة، أنتم أشباحٌ على ما يبدو، لكن حظكم العاثر قادكم إلى حاجزٍ حتى الأشباح لا تنفذ منه”.

ليس للأمر علاقة بالحظ من قريب أو بعيد، فالطريق إلى رفح خطٌّ مستقيم، شارعٌ يمرّ بكل الحواجز. وحاجز الخرّوبة هذا كان خاتمةً لرحلة طويلة استمرت أربع ساعات ونصف، بدأت في منطقةٍ تَرِبَةٍ تحت جسر في القاهرة، والترابُ سيكون رفيقنا الجميل.

في المَرْج تتجمع الباصات وسيارات النقل العمومي. سائق السيارة المرسيدس الخضراء ذات الثمانية ركاب طلب 400 جنيه. أحدنا اعتقد أنَّ السعر “لقطة” فانعقد الاتفاق، وعند الوصول، قبض السائق 450 جنيهاً، فالإكراميّة واجبة، والرجل تحمّل معنا ساعتين كاملتين من الجدل مع رجال الأمن، وبرد ليل الصحراء، إضافة إلى ما لحقه من إهانات المُقَدَّم. على الطريق، تبرع له اثنان منا (كلّ وحده ودون أن يعرف واحدهما عن الآخر) بعشرة جنيهات كان أبو شيماء سايس الكراج قد أثار من أجلها زوابع هاتفية لم تتوقف، وتدخّل فيها سائقون آخرون تأكيداً على خطورة الموقفِ الذي بانَ في ارتجاف صوت السائق سعيد: “والله العظيم يا عُودة إنّو مالوهْشِ عندي غير الكَرْتَه، بَسْ أعْمِلِ إيه… أنا اللي أسوق وأتعب وهُمَّه يشاركوني فْ أكلِ عيشي”.

عودة هو الاسم الحركي الذي أعطاه السائق سعيد لمن يتلاطف معه منا. وعودة سيكتشف لاحقاً أنه أَكَلَ بُمْبَه في صديقه، وأن أُجرة الرحلة التي قمنا بها لا تتعدى في الواقع الـ230 جنيه، وأن الـ100 جنيه التي تقاضاها سعيد في اليوم التالي لنقلنا من العريش إلى رفح و”والله العظيم إنو دي أُجرة مخصوصة ليكو، أَصْل أنا حبّيتك يا عُودة” كانت استكمالاً لمشروع استغفالنا، فالأجرة الحقيقية هي 40 جنيهاً فقط.

“ليست مشكلة، مجرد إعادة توزيع للثروة” هكذا قلت، وهكذا وقفنا في منتصف المسافة بين العريش ورفح في إعادة توزيع أُخرى: توزيعنا!

“ليس لديكم تنسيق. المفروض أن يكون معكم كتاب تسهيل مرور من سفارتكم. أنا لا أستطيع أن أفعل أي شيء لمساعدتكم. اعذروني. قمنا بالاتصال بالمركز، وسننتظر التعليمات”. وانتظرنا بين دخائن السجائر والقهوة المرّة والأحاديث الصغيرة. كنا لُقيةً لرجال الأمن، مجموعة من الكُتّاب والفنانين المتحمسين للحوار حول كل شيء وسط ملل اناسٍ مرميين في رتابة اللامكان. كان اللقاء دافئاً، رغم المنع.

“لا موافقة، حاولوا غداً”. عدنا إلى العريش على أمل، والغد لناظره.. بعيد.

§

ثمّةَ منطادٌ أبيضُ يُقال إنّهُ يُستعملُ للرّصد. ثمّةَ طائراتٌ، ثلاثٌ بالتحديد، تَخدِش وجه السماء. لا صوتَ ولكن ثمّةَ عمودٌ أسودُ يرتفعُ من اليمين، وآخر من الوسط: الدّخان هناك، أمامك، على مسافة امتداد الذراعِ وخفقةِ القلبِ وانتشار الرّائحةِ، وهيَ -الحبيبةُ- أيضاً هُناك، أمامك، تفرد شَعرَها على طرفِ البحرِ ويصطدمُ الزّبَدُ الأبيضُ بساقيها العاريتين.

إنها هناك، أمامك. تمدُّ يدك وتكاد تلمسها، تكادُ ولكن قبل انتقالِ الرّعشةِ ترتفعُ الجدران والبوّاباتُ والعسكر لتَقْلِبَكَ على ظهرك. ها هُم يَظهَرون بالعشرات: ممنوع المُرور، ممنوع التّصوير، ممنوع الجُلوس، ممنوع الوقوف، ممنوع البقاء، ممنوع العودة، وها أنت تتحوّل إلى صرصارٍ هاربٍ من كومة الأحذية الهابطةِ على رأسك.

كان لا بدّ لهم من التبعثرِ وسط كومةٍ من الفرنسيين والتخفّي خلف البشراتِ البيضاء ليمرّوا كغبار الصحراء بين القضبان الحديدية، لكن أمام الكتلةِ الكونكريتيةِ الواقفة بكامل صحوها، حتى نسمةُ الهواءِ الفرنسيةِ البيضاءِ لا تمرّ: هنا ميناء رفح البرّي.

§

الحُدود. ذلك الخطُّ الفاصلُ بينَ هُنَا وهُنَا. ذلك الخطُّ الفاصلُ بين ما كُنّا وما نحنُ الآن. ذلك المَجازُ، ذلك التّيهُ، ذاكَ التشرّد.

الرّمال تتلوّى كأفعى على الأسفلت، تنسابُ من تحت أرجلنا ومن تحتِ البوّاباتِ، ونحن نقفُ نبحثُ عن ثغرةٍ بين رجالِ الأمن. ها هي فلسطين على بُعْدِ أمتار. ترابٌ بعد التراب الذي تقف عليه. ترابٌ هو التراب نفسه الذي تقف عليه. ورغم ذلك، هناك “فلسطين” وهنا “مصر”. هنا تقف وتمشي، وهناك بعيدٌ كمجرّة أخرى، ومحرّم كثمار شجرة المعرفة. وأنت أقل من حبة الرمل التي تدفعها الريح من تحت البوابات.

“حِرصاً على سلامتكم”، “ليس معكم وثيقة تسهيل مرور من سفارتكم”، “أنتم أُردنيون، ما دخلكم بغزّة؟”: لم تكن الطائرات الإسرائيلية هي الوحيدة التي قَصَفَت تلك الظهيرة، ولم يكونوا ليستسلموا للقصف، فهم حاضرون بكامل عتادهم: العودُ، حناجرهم، والناس. التمّوا كقبضةِ اليد الواحدة، وانهالوا بأغنية.

لن نموت، ولن نَسمحَ بموت أولئك في الداخل. هم لم يموتوا: لا يموتون كلّ لحظةٍ وكلّ يوم. هذه المعابر/الحواجز لن تقطّع أوصالنا: فما زالوا هناكَ يصرُخون بأعلى أصواتهم من على طرفي الجولان، ويُحاولون دائماً اجتياز الشريعة، ويَمخُرون إليها بسفنٍ قديمة، ونقفُ على المعبر بكامل حُزننا.

سنَعبُر.

2- محمّد حَمَد الحنيطي

الجنازةُ مهيبة. سُجّيَ الجُثمان على عربةِ مدفعٍ وسار خلفها الناس: الوفود العربيّة، شيوخُ العشائر، والملك نفسه، يتقدّمهم جميعاً صفوفٌ من الثوّار: عمالقةٌ مُزنّرون بالرصاص، تهتزّ بنادقهم على الأكتاف مع وقعِ الخُطى القويّة.

أيّامٌ بطولها قضاها المئاتُ مُفترشين عباءاتهم وملتحفين السماء أمام بيت محمّد الحنيطي على انحدار جبل اللويبدة بانتظارِ النّعشِ القادم من حيفا. ما أن أطلّ من بعيدٍ، من آخرِ طريقِ السلط، حتى لَعْلَعَ الرّصاصُ. يومٌ كيومِ القيامة: ها قد عاد الشّهيد.

عبد الحليم النّمر ورجالات السلط عَيّوا إلّا أن يبيت النّعش عندهم يومين. “هذا الرجل ابننا” قالوا وأغلقوا عليه عيونهم، ثم ساروا به إلى عمّان.

§

كلبُ الأثر، ذاكَ الذي أحضرهُ محمّد الحَمَد معه من حيفا ذاتَ عَوْدَة، يقفُ كُلّ ليلةٍ على سورِ الدار في أبو علندا، يواجِهُ الغرب ثمّ يبدأ بالنّواح، يبكي بكاءً مُرّاً يُقطّعُ القلب.

“إذبحوا الكلب، تَرَى محمّد عُمْرُهْ ما يِرْجَعْ”، قالها أبو خالد مختار الحنيطيين، وكزَّ على أسنانه.

§

أقصرُ الطّرُق الخطُّ المُستقيم، وهكذا ساروا على طريق السّاحل. انطلقوا من بيروت يريدون حيفا بقافلةٍ من السيّاراتِ المحمّلةِ بالأسلحة وشاحنتينِ متروستينِ بالمتفجّرات.

في رأس الناقورة أبلغ عنهم الضابط الإنجليزيّ، وعندما وصلوا عكّا حذّرهُ سُكّانها: “يا محمّد بيك، ربما علم الصهاينة عن قافلتك، هناك أخبارٌ عن كمينٍ لكَ لم ينجح في عين سارة قرب نهاريّا. إنْسَ الطريق السّاحليّ فهي مقتلك. عُدْ إلى بيروت ومنها إلى دمشق فإربد فحيفا، طريقٌ مسارُهُ ثلاثةُ أيّامٍ لكنّهُ سينقذ حياتك”. “أو اشحن أسلحتك بالبحر” اقترح آخرون، “على الأقل، بِتْ عندنا الليلة”.

“الطريقُ الآمنُ ثلاثةُ أيامٍ، والبحر حبالُهُ طويلة، وحيفا تركتها وحيدةً على الشرفة، تنتظر بحّارها الذي ركب أنهر الأسفلت نحو الشمال قبل أيام. حبيبة البحّار لا تنام، ولا تحبّ الانتظار” قال محمّد بيك، “يا إخوان، حيفا بلا أسلحة. لن ينتظرها هؤلاء الأوغاد. إن مسّوها سأكون قد مِتُّ حينها أيضاً. فَلأَمُتْ في حُضنها، مُحاولاً الدّفاع عنها، بدلاً من الموتِ متفرّجاً عليها تُستباحُ من بعيد”، ثم سار إلى الجنوب ولم ينظر إلى الخلف.

§

كانَ نبيهاً وذكيّاً ومتعلّماً، وكانَ الإنجليزيُّ المشوَّهُ يَلُفُّ على العشائر ليأخذ أبناءها جنوداً في جيشه.

محمّد الحنيطي، ابنُ الباشا حاكم المنطقة النافذ أيّام العثمانيين الذي كان يخيفُ جنودَ الأتراك نَهّابي البيادِر وآخذي السُّخرة، وابنُ الكُرديّةِ الدمشقيّةِ التي أصرّت على تعليمه فدرَسَ على شركسيٍّ ببابِ الجامعِ الكبيرِ في عمّان، كان ينامُ والكتابُ على وجهه. يحاجج ويناقش وينسكبُ الذّكاء من عينيه، فالتقطه جلوب فوراً، ليثبتَ جدارته في العسكريّة، ويعيّن ضابطاً في حيفا.

وكما ينبغي لشابٍّ ذكيٍّ يحفر في رأسه الإنجليز والصهاينة كلّ يوم، صار الضابطُ يأخذ ما يقع تحت يده من سلاحٍ ويورّده إلى الأهالي. بعدها، جمع جنوده وخطَبَ فيهم: “يا رجال، تخلعون لباسكم العسكريّ مساءً، تلبسون المدنيّ، وتدرّبون الأهالي على القتال”. وهكذا كان.

وكما ينبغي لقائدٍ عسكريٍّ ميدانيّ يعرف عدوّه ويعرف ما يتطلّبه الأمر لهزيمته، نسج علاقات دمٍ مع إخوة السلاح من الثوّار، والتقى بقادتهم المحليين: رشيد الحاج إبراهيم، وسرور برهم، والعبد الخطيب، وأبو نمر، ومحمد أبو عزيز، وأبو علي دلّول، وحسن شبلاق، وأبو إبراهيم عودة، وراشد الزفري، ونمر المنصور، وجميل باكير، ويوسف الحايك. صار البدويُّ الوسيمُ منهم.

هل قلتُ: صار منهم؟ ليسَ صحيحاً، لقد كان منهم منذ صاح معلناً ولادته على أطراف الصحراء، وكانوا منه منذ أن سَحَبَ نَفَسَهُ الأوّل. كانوا واحداً.

“أنتَ أُردني يا محمّد بيك، ما لكَ وللفلسطينيين؟” قال له جلوب وهو يُلَوّح بتقارير جواسيسه في الهواء.

“يا باشا، أنتم من رسمتم حدود هذه البلاد، قَبْلَكُم ما كانت فلسطين ولا الأردن ولا لبنان ولا سوريا. قَبْلَكُم كنّا نَشْتَري من أسواق دمشق، ونُشَتّي على ساحل المتوسّط. يا باشا، دفاعي عن حيفا هو دفاعٌ عن قريتي أبو علندا. هاكَ رُتَبَك، فرُتَبُ الثوّار أعلى”.

حين عاد من تلك المواجهة، كان مُزَنّراً بالرصاص وبارودته على الكتف: خلع زيّ العسكرية ولبس زيّ الثورة، وصار القائد العسكري الأعلى لحركة الجهاد المقدّس في لواء حيفا. لن يطَأَ بهِ أحدٌ بعد اليوم، ولن يُخفضَ رأسَهُ ولو جعلوهُ مَلِكاً.

كَمْ مِنْ مَلِكْ جَبَّارْ ظالِمْ عَنِيدِ

ظَلّ على الدِّنيا يجَرْجِرْ ثْيابَهْ

أضْحَتْ عْظَامَهْ مِثِلْ حَثّ الصَّدِيدِ

واليومْ بالرِّجْلينْ كِلْمِنْ وَطا بَهْ.

لنْ يَطَأَ به أحدٌ بعد اليوم: وحّد القوّات المدافعة عن المدينة في جيشٍ صغيرٍ من ثلاثمئة وخمسين مقاتلاً، وزّعَهم على عشر مناطق، لكلّ منطقةٍ قائد. حيفا الوديعةُ التي تُلقي رأسها بدلالٍ في المتوسّط، وتُعانِقُ الخليج، صارت نَمِرَةً بأنيابٍ ومخالبَ هم أولادها المنبثقين من رحمِها وما خانوا لَبَنَ ثديها.

§

ما أن عَبَرتهم درّاجةٌ ناريةٌ كالبرق، حتى وجدوا براميل تتدحرج أمامهم على الطريق، وانهارَ عليهم وابلٌ من الرّصاصِ والقنابل اليدوية. محمّد الحمد أمر سائقه بالاندفاع، وكذا فعل سائق الشاحنة الأولى، لكنّ حاجز النار كان أقوى فبدأ الاشتباك.

الشاحنة الخلفية استدارت عائدة إلى عكّا، لكن المقاتلين نزلوا إلى حيث قائدهم ينام على الأرض حاضناً بندقيته. كان سرور برهم يزحف ويتشقلب بين الأزيزِ وأنفاقٍ صغيرةٍ تتشكّلُ توّاً في الأرض ليصل إليه. “محمّد بيك..” هزّهُ بعنف، “رُدّ عَلَيّ يا خْوي..”، ومحمّد لا يردّ. كان خيطٌ رفيعٌ من الدم ينسابُ من حيث تلتقي شفتاه. كان هادئاً تماماً كما لم يكُن من قبل. لقد عاد محمد الحنيطي إلى حيفا.

بطرف عينه، شاهد سرور مسلّحي البالماخ يعتلون الشاحنة ويسيطرون عليها. تحسّس جيبه فوجدها. “عُرسُنا اليوم يا حبيبتي..”، قال وهو ينزع مسمارها، وركض. ثقوبٌ حمراءُ تفتّحت في ظهره. دبابيسُ مجنّحةٌ قطّعت أحشاءه، لكنّ يداً خفيّةً حملته، وقدمينِ ليستا قدميه دفعتا خطواته إلى أن وصل الشاحنة، وانفجر.

مساء يوم الأربعاء 17/3/1948، أقسم سكان الشمال الفلسطيني والجنوب اللبناني حتى صيدا، أن الأرض اهتزّت تحتهم، وأن بيوتهم تحرّكت، وأن رجُلاً شوهد يطيرُ في الهواء ويهبطُ على سطح إحدى عربات القطار المتوجه إلى عكا.

§

“هيه يا عبد الرزّاق، هيه يا عبد الرزّاق..” صاح ولدٌ من خارج الباب، “صورة أبوك بالجرايد، قال استشهد”. كان العنوان يغطّي الصفحة الأولى من جريدة الدفاع، بالأحمر: استشهد الذي دوّخ الصهاينة. “كانوا يتهدّدونه في إذاعاتهم وما كانوا يتهدّدون الزعماء العرب..” ورد في نصّ الخبر. قامت أم محمّد وسكبت دلال القهوة على الأرض، وارتفعت الزغاريد.

حين كشفوا عنه أَمَام أهله، كان وجهُهُ كما في الصورة المعلّقة على الجدار، بل أشدُّ بهاءً، وقال بعضهم إنهم شموا رائحةً عطرةً تنبعث منه: رائحةُ برتقال.

لم يتغيّر فيه شيء سوى صفٍ من الثقوب في الصدر. “بَطَلْ يا وْلِيدِيْ، ما أَعْطِيتْ قَفَا”، قبّلتهُ أمهُ على جبينه، وسارت الجنازة.

خلف النعش مباشرةً، وفي صفوفِ العمالقةِ المُزنّرين بالرصاصِ المهتزّةِ بنادقهم على الأكتافِ مع وقعِ الخُطى القويّة، كان طفلٌ يركض متسلّلاً بين سيقانهم متدعثراً بأقدامهم. أحدهم دفعه بقسوةٍ، وصاح به: “رُحْ يا وَلَدْ إلعَبْ بعيد..”

“لا تْدِزّني، هاظْ أبوي..” قال الولد، فانهالت دموعُ العملاق إذ ضرب رأسه، وحمل ابن الشهيد على كتفيه.

§

بيان اللجنة القومية لمدينة حيفا، 19/3/1948

نعي شهداء أبطال

هذه قافلةٌ من قوافل الشهداء تلقى ربّها عاملةً مجاهدةً في سبيل الوطن، ولا يسع اللجنة القومية لمدينة حيفا إلّا أن تنعى إلى الأمة العربية الكريمة زمرةً من خيرة أبنائها ورهطاً من أعزّ جنودها وهم:

1- قائد حامية حيفا الباسل محمد بيك حمد الحنيطي.

2- سرور برهم – أبو محمود، نائب القائد.

3- فخر الدين عبد الواحد – مصري.

4- عمر خالد الخطيب.

5- أحمد خضر موسى.

6- أحمد وجيه رحّال.

7- يوسف الطويل.

8- علي كبار.

9- حسن سلامة – أردني.

10- عطا الله سلامة – أردني.

11- علي شجاع.

12- محمد مصطفى خليل.

13- ألبير الأرمني.

استشهدوا جميعاً نتيجة اعتداء غادر في الساعة الثالثة من مساء يوم الأربعاء 17/3/1948م.

واللجنة القومية، إذ تنعى هؤلاء الأبطال للأمة العربية، لواثقة بأن دمهم الطاهر لن يُنسى.

§

الانهيار

17/3/1948 استشهاد قائد المقاومة المسلحة في حيفا محمد حمد الحنيطي ومساعده سرور برهم في كمين لقافلة الأسلحة التي كانوا يرافقونها، نفذته قوات البالماخ الصهيونية.

6-8/4/1948 فشل هجوم قوات جيش الانقاذ بقيادة فوزي القاوقجي على كيبوتس مشمار هعيمق الواقع على طريق حيفا – جنين، والصهاينة يقومون بهجوم مضاد يعزلون خلاله قرى عربية كثيرة ومحيط حيفا.

8/4/1948 استشهاد القائد عبد القادر الحسيني في معركة القسطل وسقوط القسطل.

9/4/1948 مذبحة دير ياسين.

22/4/1948 سقوط حيفا بأيدي قوات الهاجاناه الصهيونية.

14/5/1948 بن غوريون يعلن إنشاء دولة إسرائيل.

3- محاولة ثانية

هناك، على الحدّ الفاصل بين الحياة والموت، بين الجدار الكونكريتيّ الكالح وحقول الدحنون الحمراء، كانت أصابع عتيقةٌ، ومشقّقةٌ، تخترق التّراب وتتشبّث بحافّة الأرض كمخالب لينتصب من تحتها جسدٌ فارعٌ كجبل: ذراعاه كبندقيّتانِ تستعدّان لإطلاق النّار، قدماهُ كأعمدةٍ محفورةٍ في صخور الجبالِ الليلكيّة، وجهه كمدينةٍ ظلّت تنتظر حبيبها المسافر قرب البحر.

نفض محمد حمد الحنيطي الغبار عن نفسه ونظر حوله، فوجد خلقاً كثيرين يبحلقون فيه فاغرينَ أفواههم. “من أنتم؟” خرج صوته الدافئ.

“نحن الدم الواقف منذ انسداد الشرايين بجلطات القهر”، قال الجريح.

“نحن الأغصان الممتدة إلى بيت الجيران قطعها الجار وكوّمها يابسةً خلف السور”، قالت الأم.

“نحن الممنوعون من زيارتنا وعناقنا لأننا لسنا نحنُ، يقولون”، قال منسّق الوفد الذي يريد العبور.

“أهكذا صار بنا؟ اثنانِ وستّونَ سنةً فقط سافرتُ، ومالت بنا الحالُ كَدُهُور”، قال محمّد الحنيطي في سرّهِ ثمّ صرخَ فخرج صوتهُ كالزئير، وإذ بأصابع كثيرةٍ تخرج من تحت التراب، أجسادٌ فارعةٌ تشقُّ الأرض، ينفضون عن أنفسهم الغبار، يتطلّعون حولهم ثم يعانقون بعضهم بعضاً كأصدقاء قدامى: القسّام، زياد طناش، راشيل كوري، عبد القادر الحسيني، وفاء إدريس، فراس العجلوني، فارس عودة، كايد المفلح العبيدات، دلال المغربي، أحمد عبد العزيز، سرور برهم، سعيد العاص، أحمد المجالي،… “كيف الأخبار؟ والله زمان”، “آه والله زمان يا شباب”، يعانقون بعضهم، ويبدأون المسير، فترتجّ الأرض، ومع حركتها يخرج مئاتٌ، آلافٌ، ملايين. يسيرون بكلّ لغات الأرض من كلّ جهات الأرض إلى هناك، مع خطواتهم تسقط الحواجز والجدران، ويعبرون. مع خطواتهم تعود القرى والبيوت، تعود الأسماء والذكريات، تعود الأعراس والدبكات، وتفوح رائحة البرتقال.

على بحر حيفا التقوا جميعاً، التقى كلّ من عبر من كلّ النقاط والحدود والحواجز والجدران، وكلّ من أتى من جهة البحر بزوارق قديمة. رقصوا ورقصوا حتى كان نورٌ، وأنبتت الأرض عُشباً وبَقْلاً وشجراً ذا ثمرٍ بعد أن كانت خَرِبةً وخاليةً وعلى وجهها ظلمة. وكان يومٌ جديد.

§

سفر زكريا، الإصحاح الخامس عشر

جئتُ من شرقِ النهر. كأسدٍ سأزأرُ زئيراً، ثمّ أعبرُ. لا بحدّ السّيفِ، بل بقدميَّ هاتين. ها هُم رفاقي، من تحتِ التُّرابِ يأتون، من البيوتِ يأتون، من كلّ الأمم يأتون، يمشون معي. بخطوتهِم ترتجُّ الأرض وتتصدّعُ الحيطان. موتاً سيموتونَ من أخذوا الناس بالسّيف. حرقاً سيُحرقون من أسالوا أنهار الدّم. هُوَذَا ربُّ الجُنُودِ ينادي شعبه: بالنّارِ آتي ومركباتي كزوبعةٍ لأردّ بِحُمُوٍّ غضبي وزجري بلهيب النار. لكنّ الأرض ترتجّ وشعب الربّ يتفرّق ويركض. وربُّ الجُنُودِ ينادي شعبه: أنا أعطيتكم أرضاً لم تتعبوا عليها، ومدناً لم تبنوها، ومن كرومٍ وزيتونٍ لم تغرسوها تأكلون، أعطيتكم عبيدكم وإماءكم من الشعوب الذين حولكم، تستعبدونهم إلى نهاية الدهر. لكنّ الأرض ترتجّ وشعب الربّ يتفرّق ويركض. الناس من أربعة أرجاء الأرض يعبرون، ويكون يومٌ كيوم الحشر، كبرج بابل. كل الألسن تأتي، وتكون مملكة العدل، وتصير مملكة السيف التي كانت سخطاً على كل الأمم خَرِبةً وهالكة.

—————————————————

ملخّص صحفي: “مُنع وفد “مثقفون أردنيون من أجل غزة” من دخول القطاع عبر معبر رفح المصري يوم 17/2/2009، بعد أيام من انتهاء عملية الرصاص المسكوب الإسرائيلية وإحكام الحصار. استمرت المحاولة لمدة ثلاثة أيام متتالية دون نجاح، قام خلالها الوفد بالاعتصام والغناء والتظاهر وإقامة معرض للرسوم الكاريكاتورية التضامنية في عرض الشارع أمام المعبر. وتشكل الوفد من الكاتب والقاص هشام البستاني، الفنان التشكيلي محمد نصر الله، الموسيقي والفنان كمال خليل مؤسس فرقة بلدنا، المخرج عائد نبعة، رسام الكاريكاتير عبد الرحمن الجعبري، الإعلامية كوثر عرار، والكاتب يوسف أبو جيش، والباحث يحيى أبو صافي. يتوقّع وصولهم إلى عمّان غدًا.” صحيفة الغد، 20/2/2009.

كَمْ مِنْ مَلِكْ جَبَّارْ…: إلى آخر القصيدة النبطيّة هي من نظم محمد حمد الحنيطي نفسه.

الرجل الطائر: هو محمود أبو سالم من قبيلة خضير – عشائر بني صخر، وكان حارساً شخصيّاً للقائد محمد الحنيطي، والشخص الوحيد الذي نجا من الكمين عندما رفعه الهواء الناتج عن الانفجار مئات الأمتار ملقياً به فوق إحدى عربات القطار المتوجه إلى عكا.

القسّام: عز الدين، من بلدة جبلة قرب اللاذقية، ولد عام 1882، حكم عليه الاستعمار الفرنسي بالاعدام نتيجة لمشاركته في مقاومتهم، فغادر عام 1920 إلى حيفا وبدأ بتأسيس نواة للمقاومة المسلحة ضد الاستعمار البريطاني والصهاينة. استشهد ليلة 19/11/1935 في معركة مع الجيش البريطاني في أحراش يعبد، ودفن في قرية بلد الشيخ جنوب شرق حيفا.

زياد طناش: من بلدة حوّارة قرب إربد، كان عضواً في الحزب الشيوعي الأردني منذ شبابه المبكّر، وانضم أواسط السبعينيات إلى قوّات الأنصار، التنظيم المسلّح للشيوعيين والمتواجد في لبنان لمواجهة إسرائيل. عرف عنه بطولته ووقوفه في وجه الدبابات الإسرائيلية. استشهد عام 1976 إثر غارة للطيران الإسرائيلي. دفنه صديقه الشاعر عز الدين المناصرة بيديه في مقبرة الشهداء في بيروت. أثناء الدفن، أشارت امرأة من مخيّم شاتيلا إلى الجثة وقالت: “انظروا، لا يزال جرحه أخضر”، فكتب فيه المناصرة قصيدته الشهيرة: “بالأخضر كَفَّنّاهُ”، التي غنّاها مارسيل خليفة لاحقاً.

راشيل كوري: إحدى عضوات حركة التضامن العالمية مع فلسطين، ولدت عام 1979 في مدينة أوليمبيا عاصمة ولاية واشنطن الأميريكية، واستشهدت بعد أن دهستها بلدوزر إسرائيلية نوع كاتربلر D9 ، كانت راشيل تحاول منعها من هدم بيت في غزة وذلك يوم 16/3/2003.

عبد القادر الحسيني: ولد عام 1910، قاد المقاومة المسلحة في قطاع القدس عام 1948، واستشهد في معركة القسطل يوم 8/4/1948.

وفاء إدريس: أول استشهادية في انتفاضة الأقصى التي اندلعت عام 2000، فجّرت نفسها في شارع يافا في القدس الغربية المحتلة يوم 27/1/2002 بعد يوم واحد من القصف الإسرائيلي بطائرات إف 16 لمدن غزة وطولكرم ونابلس.

فراس العجلوني: رائد طيّار في الجيش الأردني، ولد في عنجرة من قرى عجلون شمال الأردن، واجه وحده أسراب الطيران الإسرائيلي في حرب حزيران 1967 بعد أن استطاع التحليق بطائرة نجت من قصف الطائرات العسكرية وهي جاثمة على أرض المطار. قصف العمق الإسرائيلي مرّات عدة خلافاً للأوامر بعد أن أعاد الهبوط والإقلاع، واستشهد بعد أن قصفته الطائرات الإسرائيلية وهو يحاول الإقلاع للمرة الأخيرة. كان ذلك يوم 5/6/1967.

فارس عودة: الطفل الفلسطيني الذي التقطت عدسة الكاميرا صورته وهو يرفع حجراً بيده الصغيرة أمام دبابة إسرائيلية، وتحولت تلك الصورة إلى إيقونة من إيقونات المقاومة ضد الظلم. استشهد بنيران الإسرائيليين أمام معبر المنطار في قطاع غزة في الثامن من نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني سنة 2000 دون أن يتجاوز الرابعة عشرة من العمر. وكان فارس قد أخبر أهله مراراً أن ابن خالته شادي الذي سبقه في الشهادة أتاه في الحلم طالباً الانتقام لدمه.

كايد المفلح العبيدات: الملقّب بصقر فلسطين، ولد في كفر سوم قرب إربد شمال الأردن، استشهد في هجوم على القوات البريطانية عام 1920 في منطقة تلال الثعالب في فلسطين.

دلال المغربي: ولدت عام 1958 في مخيم صبرا في بيروت، قادت عملية حملت اسم “كمال عدوان” ثأراً لاغتياله عام 1973، استطاعت مجموعتها الفدائية السيطرة على باص بركّابه على طريق حيفا-تل أبيب ظل يسير في الشوارع رافعاً علم فلسطين، إلى أن اشتبكت مع قوات خاصة إسرائيلية يقودها إيهود باراك حتى نفدت ذخيرتها، واستشهدت يوم 11/3/1978.

أحمد عبد العزيز: البطل أحمد عبد العزيز، ولد عام 1907 في الخرطوم حيث كان والده قائد الكتيبة الثامنة بالجيش المصري هناك. قاد الفدائيين المصريين إلى فلسطين بعد استقالته من الجيش المصري عام 1948، واستطاع تكبيد الصهاينة خسائر فادحة، وباستشهاده ليلة 22/8/1948، يقول الأردني عبد الله التل قائد معركة القدس عام 1948، “خسرت الجيوش العربية قائداً من خيرة قوادها”. دفن شمال بيت لحم.

سرور برهم: ولد عام 1903، وكان من أتباع القسّام، وشكل مع آخرين مجموعة “الكفّ الأسود” التي عملت ضد قوات الانتداب البريطاني والاستعمار الصهيوني في فلسطين. انضم إلى حامية حيفا التي دافعت عن المدينة تحت قيادة محمد الحنيطي، وكان نائب قائد الحامية. قتل في الكمين الذي نصبه البالماخ لقافلة الحنيطي العائدة بالسلاح للدفاع عن المدينة يوم 17 آذار 1948.

سعيد العاص: من مواليد حماة، وهو أحد قادة الثورة السورية عام 1925 ضد الاستعمار الفرنسي، وشارك في ثورة 1936 في فلسطين واستشهد يوم 6/10/1936 على الجبال الواقعة بين القدس والخليل، ودفن في قرية الخضر غرب مدينة بيت لحم.

أحمد المجالي: هو أحمد دحيلان المجالي من مواليد عام 1963، استشهد عام 1983 على خطوط المواجهة مع إسرائيل في لبنان، كتب له الشاعر إبراهيم نصر الله “أغنية حب لشهيد الكرك”، وغنتها فرقة بلدنا بألحان مؤسسها كمال خليل، ومن كلماتها: “هذي فلسطينك إلَكْ / هيِّ إلَكْ / مثل الطْفُولِه وصدر إمَّكْ والكركْ / هيِّ إلَكْ”، وعائلة المجالي هي من العائلات البارزة في محافظة الكرك جنوب الأردن.

الإصحاح الخامس عشر من سفر زكريا: إصحاح كان مفقوداً ووجد في كهوف قمران مع وثائق الأسينيين المعروفة باسم مخطوطات قمران، وهو غير مدرج في النسخة المعروفة من الكتاب المقدّس.

[ألبومُ الصّورِ المنسيّة]

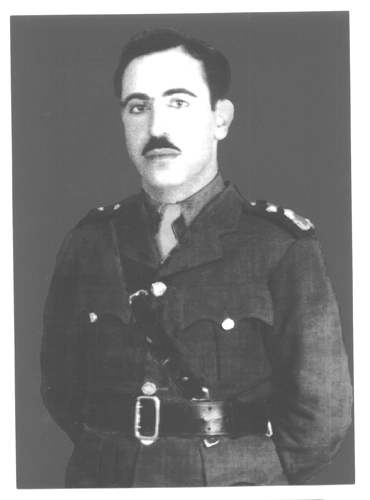

القائد محمد بيك حمد الحنيطي باللباس العسكري – 1946

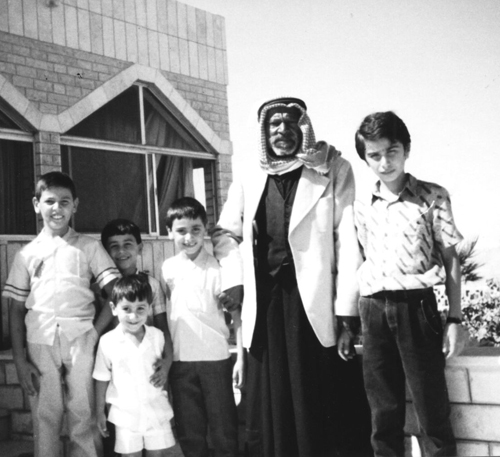

محمود أبو سالم مع أحفاد الحنيطي- 1986

هشام البستاني هو كاتب من الأردن، صدر له: عن الحب والموت (دار الفارابي، 2008)، الفوضى الرتيبة للوجود (دار الفارابي، 2010)، أرى المعنى (دار الآداب، 2012)، مقدّمات لا بدّ منها لفناءٍ مؤجل (دار العين، 2014). وصِف بأنه “في طليعة جيل غضب عربي جديد، رابطًا بين حداثة أدبيّة لا تحدّها حدود، وبين رؤية تغييرية جذريّة”، وبأنه “يعيد إنتاج موجة سيريالية جديدة في ثقافة فوّتت الفورة السيريالية في القرن الماضي”. تُرجمت قصصه إلى عدّة لغات، نُشرت الإنجليزيّة منها في دوريّات بارزة في الولايات المتّحدة، وبريطانيا، وكندا، وأيرلندا. اختارته مجلة إينامو الألمانيّة كواحد من أبرز الكتّاب العرب الجدد عام 2009، واختارته مجلة ذي كلتشر ترِب الثقافية البريطانية كواحد من أبرز ستّة كتّاب معاصرين من الأردن عام 2013. حاز كتابه أرى المعنى على جائزة جامعة آركنسو (الولايات المتحدة) للأدب العربيّ وترجمته للعام 2014، وصدر بنسخته الإنجليزيّة عام 2015 عن دار نشر جامعة سيراكيوز – نيويورك. اختيرت إحدى قصص هشام البستاني لتكون ضمن الكتاب الأنطولوجيّ الأوّل لـ أفضل القصص القصيرة من آسيا، وبالإضافة إلى كتابة الأدب، فهو يقدّم عروضًا “اشتباكيّة” تدمج نصوصه مع عدّة فنون على المسرح، مثل الموسيقى والتشكيل والرّقص المعاصر؛ كما يكتب مقالات لعدّة صحف ومجلّات عربيّة وعالميّة؛ وهو محرّر الأدب العربيّ لمجلّة ذي كومون، المجلّة الأدبيّة لجامعة آمهيرست العريقة في الولايات المتّحدة. حاز عام 2017 على جائزة الإقامة الأدبيّة في مركز بيلّاجيو (إيطاليا) التي تمنحها مؤسسة روكفلر.

Hisham Bustani is an award-winning Jordanian author of four collections of short fiction /poetry. He is acclaimed for his bold style and unique narrative voice, and often experiments at the boundaries of short fiction and prose poetry. Much of his work revolves around issues related to social and political change, particularly the dystopian experience of post-colonial modernity in the Arab world. His work has been described as “bringing a new wave of surrealism to [Arabic] literary culture, which missed the surrealist revolution of the last century,” and that he “belongs to an angry new Arab generation. Indeed, he is at the forefront of this generation—combining an unbounded modernist literary sensibility with a vision for total change…. His anger extends to encompass everything, including literary conventions.” Hisham’s poetry and short fiction has been translated into many languages, with English-language translations appearing in prestigious journals across the U.S., U.K., and Canada, including “Modern Poetry in Translation,” World Literature Today, the Los Angeles Review of Books and The Literary Review. In 2009, he was chosen by the German review Inamo as one of the Arab world’s emerging and influential new writers. In 2013, the U.K.-based cultural webzine The Culture Trip listed him as one of Jordan’s top-six contemporary writers. His book “The Perception of Meaning” won the 2014 University of Arkansas Arabic Translation Award and was published in 2015 by Syracuse University Press. One of Hisham’s stories was recently chosen to be featured in the inaugural edition of “The Best Asian Short Stories” anthology, forthcoming this year. He is the recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation’s prestigious Bellagio Residency for writers for 2017.

Hisham Bustani is an award-winning Jordanian author of four collections of short fiction /poetry. He is acclaimed for his bold style and unique narrative voice, and often experiments at the boundaries of short fiction and prose poetry. Much of his work revolves around issues related to social and political change, particularly the dystopian experience of post-colonial modernity in the Arab world. His work has been described as “bringing a new wave of surrealism to [Arabic] literary culture, which missed the surrealist revolution of the last century,” and that he “belongs to an angry new Arab generation. Indeed, he is at the forefront of this generation—combining an unbounded modernist literary sensibility with a vision for total change…. His anger extends to encompass everything, including literary conventions.” Hisham’s poetry and short fiction has been translated into many languages, with English-language translations appearing in prestigious journals across the U.S., U.K., and Canada, including “Modern Poetry in Translation,” World Literature Today, the Los Angeles Review of Books and The Literary Review. In 2009, he was chosen by the German review Inamo as one of the Arab world’s emerging and influential new writers. In 2013, the U.K.-based cultural webzine The Culture Trip listed him as one of Jordan’s top-six contemporary writers. His book “The Perception of Meaning” won the 2014 University of Arkansas Arabic Translation Award and was published in 2015 by Syracuse University Press. One of Hisham’s stories was recently chosen to be featured in the inaugural edition of “The Best Asian Short Stories” anthology, forthcoming this year. He is the recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation’s prestigious Bellagio Residency for writers for 2017.

Maia Tabet is an Arabic-English literary translator living in Washington, D.C. Her translations have been widely published in journals, literary reviews, and other specialized publications, including The Common, the Journal of Palestine Studies, Words Without Borders, Portal 9, and Banipal, among others. She is the translator of “Little Mountain” (Minnesota University Press, 1989, Carcanet, 1990, and Picador, 2007) and “White Masks” (Archipelago Books, 2010, and MacLehose Press, 2013) by the renowned Lebanese writer Elias Khoury; and of “Throwing Sparks” (Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing, 2012) by Abdo Khal, the winner of the 2010 International Prize for Arabic Fiction. Her translation of Sinan Antoon’s “The Baghdad Eucharist” appeared in April 2017 (Hoopoe Press), and she has just completed her translation into English of Hisham Bustani’s collection of short stories, “The Monotonous Chaos of Existence.”

Maia Tabet is an Arabic-English literary translator living in Washington, D.C. Her translations have been widely published in journals, literary reviews, and other specialized publications, including The Common, the Journal of Palestine Studies, Words Without Borders, Portal 9, and Banipal, among others. She is the translator of “Little Mountain” (Minnesota University Press, 1989, Carcanet, 1990, and Picador, 2007) and “White Masks” (Archipelago Books, 2010, and MacLehose Press, 2013) by the renowned Lebanese writer Elias Khoury; and of “Throwing Sparks” (Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing, 2012) by Abdo Khal, the winner of the 2010 International Prize for Arabic Fiction. Her translation of Sinan Antoon’s “The Baghdad Eucharist” appeared in April 2017 (Hoopoe Press), and she has just completed her translation into English of Hisham Bustani’s collection of short stories, “The Monotonous Chaos of Existence.”