Open a Cocoon:

An Interview with Mary Cisper

by Karin Cecile Davidson

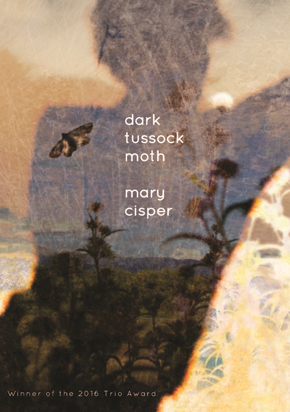

Mary Cisper’s debut poetry collection, “Dark Tussock Moth,” winner of the 2016 Trio Award (Trio House Press, 2017), is a sweeping land, crossed by drought and flood, coursed with wildflowers and white-throated sparrows, and never apologetic, always truthful, whether reflecting on the alpine monkeyflower, searching night skies for white and blue dwarfs, or bidding a glacial goodbye. This is a naturalist’s world, one in which scientist and poet meet; where ecological transformations are rendered and, by man’s hand, ruined; wherein 17th century naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian is called forth and cocoons open. In this wilderness, one experiences mountains and meltwater, conquest and confluence, metamorphosis and migration, extinction and memory. Terrain, time, weather, and ways of seeing the world from another angle—via microscopic lens, via telescope, via wide-eyed wonder—are explored here, allowing the occasion to ponder the rich, slippery relationship between man and nature.

Mary Cisper’s debut poetry collection, “Dark Tussock Moth,” winner of the 2016 Trio Award (Trio House Press, 2017), is a sweeping land, crossed by drought and flood, coursed with wildflowers and white-throated sparrows, and never apologetic, always truthful, whether reflecting on the alpine monkeyflower, searching night skies for white and blue dwarfs, or bidding a glacial goodbye. This is a naturalist’s world, one in which scientist and poet meet; where ecological transformations are rendered and, by man’s hand, ruined; wherein 17th century naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian is called forth and cocoons open. In this wilderness, one experiences mountains and meltwater, conquest and confluence, metamorphosis and migration, extinction and memory. Terrain, time, weather, and ways of seeing the world from another angle—via microscopic lens, via telescope, via wide-eyed wonder—are explored here, allowing the occasion to ponder the rich, slippery relationship between man and nature.

The way a chainsaw chases down the orchard

a child falls into the river.

Mouthwater, whose phonemes lottery over each other,most of the flowers here remain nameless

although I like saying jacaranda.–Mary Cisper, “Dream of Being Given Mountains of Apples”

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: Image, sound, scent. Form, pattern, punctuation. Tell us about these elements, how you construct your poems, especially given your trio of roles as poet, artist, and scientist.

MARY CISPER: It may be we use art and science for different ends, yet both ask me to begin without attachment. Of course, I come with baggage, prior research, tropes. Perhaps beginning a poem is akin to starting an experiment: I don’t know what will happen, but I’m curious (a kind of hopefulness?) for discovery—however private—keeping in mind what Jack Spicer said, “[…] I always am very unhappy when I say what I want to say.”

In any case, and no matter the line of questioning, there’s an initial condition: a weightless feeling (as I watch a spider ascend an invisible thread); a resonant image (say, a photograph of matted grass); or a word asking to be investigated (albedo). Something draws me—how close to approach? Does it speak? Listen. And wait—it’s almost always necessary—for accidents, encounters: something crosses the horizon; it feels sharp, embodied. Relying on the grace of the unexpected makes the process collaborative, iterative, asymptotic.

Ripeness, a petal dress.

For how a caterpillar turns into a moth, consult the literature—

Notice the candle burns all night in a paper bag on the

courtyard wall

(as I save you falling over the cliff you dream)—When are you, everything?

–Mary Cisper, “Dark Tussock Moth”

DAVIDSON: Mother, mourning, moths, Maria Sibylla Merian. “Dark Tussock Moth” parallels a family’s story with that of the 17th century naturalist, Maria Sibylla Merian, revealing that “studies show memory survives from larva to imago, the winged adult.” How did you come to realize this poem, to understand its emotional content and shape?

CISPER: I love the collage mode—the surprise of foraging—and I wanted to write a longer poem. Stumbling on something interesting—Russell’s Wave of Translation, for example—often means making an entry in my notebook. And, of course, I was immersed in Maria Sibylla Merian’s life. Her Surinam paintings of insects and plants—precise and delicate compositions depicting life cycle and ecology—conjoin art and science. In braiding together personal reverie with historic and scientific information, I think I was trying to speak to meaning. How we assign meaning to phenomena is as fascinating and mysterious as anything to me—and it’s a creative act that happens all the time. I didn’t know where the poem was headed when I started but I hoped for the elements to play off each other. If I trust enough in relation, can that guide a poem?

I found Maria’s field notes (in translation) strangely moving. Aiming for clarity, her descriptions arise out of the domestic, what she saw and touched. I never wanted to speak for her; nevertheless, her notes pierced to a small degree the opacity of having so little emotional record of her life. They speak to her effort to be truthful to what she observed.

Maybe the shortest answer is—if a poem is a vessel, how much can it contain? Among other things, time is memory of how all crisscrosses on the mind’s mysterious path—daily life, the past, science, art, the quotidian.

Above ten thousand feet, yellow Mimulus tilingii, alpine

monkeyflower, froths beside the creek.Sound, “that which indicates the presence of a speaker.”

Roaring back at the ocean, picking up broken pieces of shell.I make you pluck the hornworm off the tomato plant. Often

mistaken for a hummingbird, its moth visits the honeysuckle at twilight.–Mary Cisper, “(Field Notes)”

DAVIDSON: Throughout the collection are the recurring “(Field Notes),” set at intervals where one can pause, look closer at a flower petal or a feeling, count tree rings, stand in the rain, experience surprise or disappointment, find oneself lost. Where did you gather these thoughts, moments, discoveries, and what was the process of including them in the collection?

CISPER: A visual artist has her tubes of color, inks, pencils, and brushes for placing marks on a surface. Accordingly, I think of my notebook as an always handy tool (I must be faithful to!) for recording observations, words, quotes, dreams, crap, an occasional sketch, and, of course, drafts of poems. The “(Field Notes)” were distilled from entries made over a period of a couple of years. (My mind is a sieve. As a chemist, I made sure to keep meticulous records. What else to do?)

CISPER: A visual artist has her tubes of color, inks, pencils, and brushes for placing marks on a surface. Accordingly, I think of my notebook as an always handy tool (I must be faithful to!) for recording observations, words, quotes, dreams, crap, an occasional sketch, and, of course, drafts of poems. The “(Field Notes)” were distilled from entries made over a period of a couple of years. (My mind is a sieve. As a chemist, I made sure to keep meticulous records. What else to do?)

When I started putting “Dark Tussock Moth” together, I began with a small set of notes—then realized they could be expanded to play not only as “notes” to the poems, but circle in an open, more discursive way. Expanding them allowed me to divide “Dark Tussock Moth” into sections; I see them as marking a place of rest and, maybe, detachment.

In what way is a butterfly house made of desire?

–Mary Cisper, “Mist Net”

DAVIDSON: Recently, in the New York Times, Matthew Zapruder wrote, “In poetry, our familiar language can start to feel resonant with significance, more alive, even noble. The words we use in our everyday lives carry along with them deep reservoirs of history (personal and collective) that can, through a poem, be activated. In a poem, language remains itself yet is also made to feel different, even sacred, like a spell.” In terms of background influences and inspiration, and in reference to your training and work as artist and chemist, how would you respond to this?

CISPER: Matthew was one of my teachers, so it’s doubly fun to respond to his quote. I can imagine most writers feeling words are sacred elements. I know I feel that; at the same time, I often find myself questioning them. Both science and poetry teach me to be very careful with words, for what’s a lie made of? Yet, the fact that we identify some language as lies speaks to the test of truth we commonly hold language to. (I hope.) I can’t avoid feeling that words create (logos). Words are energy—they move us. Even the simplest parts of speech set up relation and structure.

Besides everyday language, many other vocabularies act as reservoirs for other forms of knowing and feeling. Borrowing from specialized vocabularies and mixing it up can be, I think, sexy. A friend of mine, a climate scientist, quotes lines of poetry at the head of his scholarly chapters. Even scientific writing aims to cast a spell.

It’s knitting weather, the a in beachcomber

narrows a pelican’s eyes,

cumulus means a heap.–Mary Cisper, “Cool White Roof”

DAVIDSON: Preface to the poem, “Cool White Roof,” is the note: “Geoengineers propose large-scale spraying of seawater as a way to increase the reflectivity of maritime clouds and cool the Earth.” The lens here shifts from sky to earth to sea, clouds to “rough basalt” to “blood-orange sea stars,” allowing the reader a global view of interconnection. Science and language are perfectly married here, as in all the poems of “Dark Tussock Moth,” and allied with a deep concern of ecological imbalance. Would you reflect on how you feel poetry aligns with the natural world in terms of action, awareness, and preservation?

CISPER: Blooming datura and New Mexican sunflowers against sagebrush as passenger and driver start for Wyoming. My beloved notices horses galloping in a field; I do not. Writing is a process of distillation (like trying to rain? so is reading like being rained on?). Words—do they stand for the connections the writer observed? Or, are they the connectors? Each side of the road, a yellow fraying. To amplify the truth of its being golden, call it veritable. High desert rain has ignited blue flax, red gaillardia. Cerro San Antonio slopes upward in memory of fire that happened ages ago. In looking, do we ever get to the bottom of looking? (In hearing, the bottom of hearing?) What to do has always been my question. How to be present with the give and take? Does my own longing reflect some undercurrent that drives becoming?

West Spanish Peak appears. “Live Bait sold here.” Worrying about aquifers, bees … A pinkish swath of Cleome serrulata, Rocky Mountain bee plant: “In times of drought early Spanish-Americans made tortillas from the barely palatable but nourishing seeds.” Passing a snowmelt lake, I think willful ignorance—not death—is tragic. “I don’t know the rivers, babe.”

Escaping the slow drag of a car turning left, “Welcome to the land of tailings.” A billboard advertises jobs in molybdenum mining. “They took down a whole mountain there.” I want to think awareness (how to convert knowledge to language?) is action. “They filled the valley with the waste?” One of the actions, anyway. (Who is they?) Stopping to get our bearings, notice a fake tree cell tower. Fireweed. A friend texts, “Bring me a moonrock.”

Shopping carts. Sandwiches. In a grocery store parking lot feeling awe knowing everything is made out of Earth. (How we seem made to convert, transform, and destroy, then miss what we started with.)

An outcrop of granite is a map of awareness; even a tailings pile points to what’s missing. Because meadows speak texture, complexity, innumerable burstings-forth—everything, I would map the asters in this field near the Wind River Range. Dotted with purple and bees. What is my awareness except a sketchy map following the thin edge of the little I know? Attention shifts: the sum, the collective, the whole evolves. Long before I feel it, I hear the noise of the wind—staccato, almost a fusillade—moving through the pines.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor