Gabriel Blackwell Presents

a review by Brian McKenna

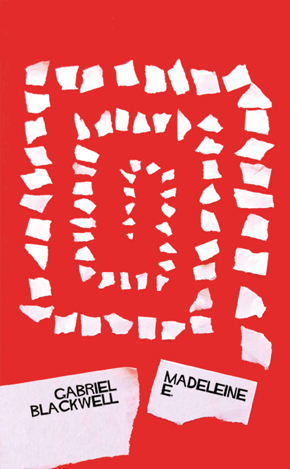

Gabriel Blackwell, “Madeleine E.”

Outpost19

2016, 284 pages, softcover, $16.00

Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” is a film of singular pleasures working in perfect concert, each adding to the diaphanous haze of plausibility that slowly descends on our better judgment. By the time the fraught, romantic strains of Bernard Herrmann’s score begin to accompany acrophobia-stricken detective John “Scottie” Ferguson (Jimmy Stewart) on his peregrinations around the city of San Francisco, following a green Jaguar driven by the woman he believes to be Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak), all the filmmaking elements of Hitchcock’s meticulously crafted “Vertigo” have dovetailed into cinema of narcotic power. We follow Scottie following Madeleine. To the flower shop that looks like a Richard Estes painting. To the sun-bleared cemetery at Mission Dolores. We’re seduced along with him, our skepticism dissolving in the light of Robert Burks’ immaculate cinematography, Edith Head’s arresting costume design, Bernard Herrmann’s hypnotic score. Such is the captivating power of the film obsessing the protagonist in Gabriel Blackwell’s latest literary consternation, “Madeleine E.”

Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” is a film of singular pleasures working in perfect concert, each adding to the diaphanous haze of plausibility that slowly descends on our better judgment. By the time the fraught, romantic strains of Bernard Herrmann’s score begin to accompany acrophobia-stricken detective John “Scottie” Ferguson (Jimmy Stewart) on his peregrinations around the city of San Francisco, following a green Jaguar driven by the woman he believes to be Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak), all the filmmaking elements of Hitchcock’s meticulously crafted “Vertigo” have dovetailed into cinema of narcotic power. We follow Scottie following Madeleine. To the flower shop that looks like a Richard Estes painting. To the sun-bleared cemetery at Mission Dolores. We’re seduced along with him, our skepticism dissolving in the light of Robert Burks’ immaculate cinematography, Edith Head’s arresting costume design, Bernard Herrmann’s hypnotic score. Such is the captivating power of the film obsessing the protagonist in Gabriel Blackwell’s latest literary consternation, “Madeleine E.”

Casting about for direction both professionally and romantically, the novel’s protagonist—also named Gabriel Blackwell—finds in Hitchcock’s masterpiece a catalyst. Cut loose early from an assistant professorship appointment and stymied in his attempts to make his obsessive research congeal into a focused whole in order to write “Madeleine E.,” the book-length study of the film “Vertigo” for which he’s been contracted, Gabriel ruminates on the film’s themes of romantic obsession, delusion, and identity. “Because my own life lacked structure,” Gabriel admits, “I looked for it in ‘Vertigo.’” Through critical engagement with the film, he also attempts to sublimate the guilt he feels about his troubled relationship, lack of serious employment, and the role he may have played in his girlfriend’s decision to get an abortion.

Ostensibly, “Madeleine E.” looks like a commonplace book, employing passages from film critics, writers, and thinkers of all stripes in a scene-by-scene examination of Hitchcock’s “Vertigo.” Scene headings borrowed from the film’s script lend structure to the book and suggest the themes taken up by the vast array of voices in each fugue-like section. Hitchcock’s own insights and tart witticisms about psychology and moviemaking rub up against thoughts and theories from a plethora of film critics, directors, authors, and philosophers, both contemporary and classic: Geoff Dyer, Robert Bresson, W.G. Sebald, Anne Carson, Judith Kitchen, John Berger, Maggie Nelson, Oscar Wilde, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Philip K. Dick, George Santayana, Robin Wood, Patricia Highsmith, and many more. To the already kaleidoscopic mélange of insight and ontological questioning this cast provides, Blackwell adds his own voice, shrewdly interspersing passages of memoir, fiction, and criticism. Themes he wrestles with in the criticism show up again, in mutated form, in the passages of memoir and fiction.

Irrespective of the machinations of a murder plot, the questions “Vertigo” raises about the nature of identity and love persist. In “Vertigo,” detective Scottie Ferguson is presumably hired to follow the wife of a man named Gavin Elster, an ex-classmate who fears his wife, possessed by the spirit of a long-dead relative, may do harm to herself. In actuality, he’s following a woman posing as Madeleine Elster, a woman named Judy Barton (Kim Novak), and he’s been recruited because his acrophobia makes him the perfect witness to a staged suicide meant to cover up the actual murder of the real Madeleine Elster. But that’s not the complex part of the story. “Vertigo’s” real complexity, the complexity Blackwell explores so assiduously in “Madeleine E.,” deals with what happens when Scottie falls in love with Madeleine, a woman who doesn’t exist, and Judy, the woman playing that part, falls in love with him.

By contrasting the paroxysms of cinematic love with the gradual accretions of a real relationship, Blackwell simultaneously illuminates both. In considering the sustaining delusions and moments of acquiescence that insinuate themselves into romantic relationships, Blackwell shows how tenuous the distinction between identity and performance actually is. Those rankling uncertainties no relationship can ever completely put to rest plague the wandering writer and detective alike:

I crossed Broadway at 16th, jogging across after the DON’T WALK sign had come on, even though I had no reason to be in a hurry. The driver of a bus pulling away from its stop honked, and I turned and saw my wife behind one of the bus’s windows, not where she was supposed to be. I couldn’t have been mistaken: Beneath the watery, shimmering reflection of the BROADWAY FLORAL sign was her face, her hair, her glasses, even what I was sure was the shirt she had been wearing when she left the house that morning.

Anyone with even a passing familiarity with the film will recognize Blackwell’s ingenious nods to its images in this short passage. The way the film’s images bleed into scenes from his daily life, like this one involving his wife’s doppelgänger, begins to make the reader question Gabriel’s reliability as a narrator. Add to this the book’s critical examinations of the concept of artificial intelligence, the legend of Pygmalion, Freud’s theory of the uncanny, and its discussions of stunt doubles, displacements, replacements, and numerous sightings of Gabriel’s own doppelgänger, and the case for an addled brain starts to make itself.

Blackwell’s prose style in “Madeleine E.” is distinguished by its almost total lack of figurative language. Even as he moves between criticism, memoir, and fiction, his analytic prose style remains consistent. This lack of differentiation blurs the line between narrative and criticism and underscores just how thoroughly his obsession with “Vertigo’s” themes has permeated his consideration of all matters. Fictional passages often take on the summarizing tone of a book proposal or film pitch, sketching out sometimes humorously hackneyed plots for alternate books he might write. While the passages of memoir feel obliquely confessional, Blackwell continually undercuts the veracity of events in ways that make determining their resemblance to reality problematic. Regardless of the genre, Blackwell writes with remarkable clarity, making extremely complex theories and ideas both engaging and eerily accessible. Nevertheless, reaching consensus about the course of events could make even the most seasoned book club run long.

Blackwell luxuriates in amplifying the resonance between the novel’s memoir and fiction and the criticism that surrounds it, coaxing out comedy, underscoring sorrows, and pulling at the interrogative threads of each scene. It’s a testament to Blackwell’s creativity that even under the scrutiny of a primed and attentive reader, the parallels he draws to the film can still sneak up on him. A case in point is the mirroring of the hostile makeover Judy endures in “Vertigo” at the hands of Scottie in order to regain Madeleine’s look and Scottie’s love. In Gabriel’s memoir, a similar acquiescence occurs, as he tries to mend his strained relationship with his partner by taking a job as a courier and paralegal in training, and letting her call the shots in the relationship: “She decided when we would go to the movies, where we would go on vacation. She bought me what she called ‘school clothes.’ She took me to get my hair cut.” In a sense this parallel to the film’s melodrama is comic, but Gabriel’s attempt to recapture the animating spirit of past love in such a superficial way is also desperate and grim.

In “Madeleine E.,” the arrangement of passages and quotes is often as revealing of emotion as their content. There are stretches where passages clustered together develop a singular intensity. In one such stretch, Gabriel compiles “[a] partial list of places I saw ‘myself,’” following it with a quote from Poe about the “inscrutable tyranny” of the double and several other quotes about the potential of photography and film to preserve the appearance of identity. The creeping dread cued up by Gabriel’s list gets magnified by this tight sequence of quotes focused on the multiplication of identity. Savoring each passage’s relation to the scene containing it and the passages surrounding it constitutes one of the novel’s primary pleasures. Even when the connections drawn seem spurious or the critical hypotheses feel like strained over-readings of character, they’re never less than engaging and charmingly self-aware.

To a certain extent, enjoyment of the novel means carrying your own weight, making the associative leaps between passages. Though “Madeleine E.” piggybacks on the structure and themes of “Vertigo,” it does establish its own digressive, essayistic rhythms. Beneath all its genre-bending and metafictional elements, the attentive reader will find recognizable humanity rather than literary antagonism. By revealing the raw materials of one man’s struggle to find a ballast and finish a book about “Vertigo,” Blackwell’s engrossing assemblage makes profound suggestions about the dialectic relationship between the appreciation of art and the creation of it.

Brian McKenna received his MA in creative writing from Central Michigan University and is currently working on his debut collection of poetry, “The Trades.” His poetry reviews appear regularly at “The Rumpus.”