Quiet Glory, Crouching Shadows, Little Wish:

An Interview with Sherrie Flick

by Karin Cecile Davidson

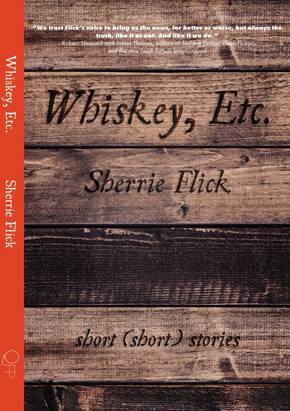

Award-winning fiction writer, food writer, freelance writer, and copy editor, Sherrie Flick is the author of flash fiction chapbook “I Call This Flirting,” “Reconsidering Happiness: A Novel,” and most recently, the short story collection “Whiskey, Etc.” (Autumn House Press, 2016). Her food writing appears in The Wall Street Journal, Ploughshares, Pittsburgh Quarterly, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and several anthologies. She lives on the South Side Slopes of Pittsburgh with her husband, Rick Schweikert, and their dog, Bubby.

Gardens, women, and music made wild; places and prospects made uncomfortable, but where one wants to linger; pie and tea and bourbon; cruel women who like men, but prefer solitude; dogs and cats and possums; moments, moods, couples, desire, and loneliness—these and more infuse energy and attitude into the 57 stories of “Whiskey, Etc.” Divided into themed sections—categories, one might call them—including songs and soap, art and pets, coffee and tea, cars and canoes, and, of course, whiskey, the collection turns unexpected corners, each precisely contained story testing versions of calm, domestic lives, as well as those that love risk, each upended in startling surprise. To enter this world is intoxicating: one might wish to stay for a brief moment, to sample one piece at a time, but the language and the lives within take hold, and pages and sections float by in suspended time.

There before you, in its quiet glory, is your garden. Finches perch on sunflowers; a blue jay flies paranoid into the neighbor’s yard: precision, noise, grace. The tomatoes heave down on their branches. The petunias have flopped into the lavender, which is touching the morning glories at the ankle of their trellis. The corn is human; the beans hectic. –“Morning Coffee” –Sherrie Flick

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: Gardens and their bounty are central to many of these stories. From gardens come peace and produce, calm and cacophony, coffee sipped and situations. Wildlife and women, along with order and disorder, appear and are addressed as well. What might you tell us of the gardens in “Whiskey, Etc.” in relation to your characters’ lives?

SHERRIE FLICK: Many of the women in “Whiskey, Etc.” are untethered. Not as rooted as some characters you might find elsewhere. They’re quick to get in a car and drive. But I think grounding them in the natural world is important. My characters want some connection and often, after the larger world lets them down, the natural world steps in to offer that comfort, whether it’s a single orange from a stand in San Francisco or a big garden stretching out toward morning. I like to think this organic space helps them move forward feeling powerful.

The little dog and the sun … The little dog and its leash … The little dog and his jangling tags … The little dog and its circling into the comforter until he’s a little hyphen wound tight. –“The Remembering” –Sherrie Flick

DAVIDSON: The unstated and understated sadness that lies inside the words of this small story is lovely and large. The language in “The Remembering” is one of lists and longing, friendship and solitude, movement and stillness, and the thoughtful emotion inside of that stillness. So many of the stories in this collection are evocative and emotional, yet this one stands alone in tenor and style. How did you find your way to writing this particular piece and discovering the narrative voice here?

FLICK: I spent a period of time. Oh, maybe six months, a year? Writing daily on the site 750words.com. How it works is you sign in and type on a blank white screen. When you hit 750 words a big green check mark appears. This is amazingly satisfying for someone like me. So, there were these endless series of early mornings where I tried to write a story a day—around 750 words. This day after day story goal led me to all kinds of experimentation I would never have tried otherwise. Some of it desperate. The early hours held me in a kind of deep solitude that led to a lot of pretty sad stories. “The Remembering” came out of this time. I wondered if I could create a narrative through repetitive statements—kind of abandoning traditional character development. I also love how, in this story, the repetition of the language stands in for plot.

DAVIDSON: Domesticity on many occasions turns unpredictable, unsettling. A paperboy seduced, a mind worn and comparing sorry to sorrow to sorrel, measurements and memory, supper made for a dead man, an argument ending in pie, an armful of gourds, the missing teenager, milk and Christmas tree lights and love like a lighthouse. Description, word choice, phrasings, moments, bits of dialogue, glimpses of lives: all of this is specifically and beautifully Sherrie Flick’s. In fact, Margo Livesey wrote to you of this collection: “You are a mistress of voice … and detail.” This is so true! Would you speak of your process, exactly how you distill language into lines to create the characters and their stories, especially the ones in which the domestic is questioned or spun or weighted?

DAVIDSON: Domesticity on many occasions turns unpredictable, unsettling. A paperboy seduced, a mind worn and comparing sorry to sorrow to sorrel, measurements and memory, supper made for a dead man, an argument ending in pie, an armful of gourds, the missing teenager, milk and Christmas tree lights and love like a lighthouse. Description, word choice, phrasings, moments, bits of dialogue, glimpses of lives: all of this is specifically and beautifully Sherrie Flick’s. In fact, Margo Livesey wrote to you of this collection: “You are a mistress of voice … and detail.” This is so true! Would you speak of your process, exactly how you distill language into lines to create the characters and their stories, especially the ones in which the domestic is questioned or spun or weighted?

FLICK: I’m one of those feminists who have reclaimed the kitchen. I personally cook and bake a lot and find the space empowering, so I’m comfortable in this setting. It’s probably no surprise kitchen tables show up a lot in my stories. There is also a lot of pie. I like the contrast of warm domestic space and the tension that can arise from discord of one kind or another placed alongside it. Many of these stories began with setting—trying to render it exactly, in detail. Then a character or two stepped in and the narrative began. I don’t usually see them coming so I follow after, curious. That’s how I write many of my drafts these days. It’s new for me, working from setting. I used to work from character and voice, and then the setting would build around him or her. At any rate, that’s how the first draft usually rises up; then I obsess over sentences and word choice and compression. I spend most of my time in revision, tinkering and adjusting, trying to build tension without too much drama. I definitely pay close attention to creating a distinct voice that doesn’t lie flat on the page. I think the death of flash fiction is dull voice.

But now, time was flying back and back, and it seemed my life would just go on forever and ever—except in the other direction. –“Back” –Sherrie Flick

DAVIDSON: Time plays a terrific role in “Whisky, Etc.” I understand, too, that time was a factor in the creation of these stories, some beginning years and years ago and finding their final versions much later. Tell us about both the usage of time in stories like “The Lake,” “Canoe,” and “Back”—in which time flies backwards—and in terms of composing the collection.

FLICK: I went to grad school in Lincoln, Nebraska. Previous to that, I had lived on either the east or west coast, near an ocean, for ten years. Previous to that, I grew up on a river near a bunch of lakes. Moving to the Great Plains from San Francisco startled me. I had never lived in such an obvious Middle, nor with such a gigantic sky. The lack of water was like an exclamation point in my head. I say all of this because the impact of that sky and that place on my writing made me think about time in a new way. I suddenly very much wanted to replicate simultaneous time on the page. The way you can wash dishes while having a vivid daydream about a long lost lover and also answer a question your husband asks you as he heads out the door. I had a strong need to examine time and that rose from not understanding place. Learning that kind of compression allowed me to explore lifetimes in flash fiction (“The Lake” and “Canoe” are a good examples of this; “Back” is an early example of me trying to examine how time can work), instead of glimpses, so it was an important lesson even if it did unsettle me to live there for four years.

DAVIDSON: Along with your chapbook and this collection, you’ve written a novel, as well as numerous essays on urban gardening, food, and libations. Are you most comfortable working in the very short form, or are you hoping to pursue another novel? And finally, do you find influence and inspiration from others who also write in the short-short form? Perhaps Michael Martone, Kim Chinquee, Amelia Gray, among others?

FLICK: I think my default writing mode is short, yes. I love to write short, but I also know I shouldn’t do it forever because I thrive on creative challenges that shake things up and make me think differently about writing. I’ve been toying with another novel and have many pages drafted, but I’ve also been writing a lot more nonfiction lately, and my next project will be a book of creative nonfiction. I’m actually about to sign that contract, and it terrifies me in the best way possible.

I have another collection of short stories already under contract that will come out in Fall 2018 with Autumn House Press. It’s similar to “Whiskey, Etc.” in that it’s mainly flash fiction with some longer stories included, but the stories are a little darker and weirder.

I love the flash fiction family of writers I’ve come to know over the years. People like Tom Hazuka, James Thomas, and Robert Shapard, who were once only fancy names on fancy anthologies, are now my friends. I greatly admire Michael, Kim, and Amelia’s work, too. It’s so great to read excellent flash—people pushing boundaries but keeping the story focused. I love Etgar Keret, Pamela Painter, Amy Hempel, and Joy Williams. I recently discovered the amazing stories of Lucia Berlin. Gertrude Stein, Raymond Carver, and Richard Brautigan were important early influences. I could go on for a long time here, so I’ll stop.

DAVIDSON: I have to include a question on one of my favorite stories, “Little Wish.” Anniversary love is considered by way of description, and aromas, ingredients, tastes, music, flowers, candlelight, even the puppy wishing a treat all set the scene. This glimpse is so stunning, so breathtaking, and an evening drifts by in under a page. Nothing is rushed. The details are perfect: the candleholders; the red wine tasting of berries and hope, pepper and lust; the heady hydrangeas; the kiss. Is it keen observation and your background in poetry that bring forth your descriptive powers? And what led you to this story?

FLICK: You’ve focused on stories that people don’t normally ask me about! I’m having to dig deep for this interview. Thanks for that. I think this might be the story to which I paid the most attention to word choice and rhythm—ever. It was carefully written with intense focus on detail, down to the cassette player. When I wrote it, I was very engaged in thinking about sentence structure and how its tiny form can drive a little story forward. I was thinking a lot about the purpose of objects in story.

The story was originally accepted into an anthology about dogs that was never published, but the editor—Stefanie Freele (another great flash fiction writer!)—asked me to think about rewriting the last sentence. In doing so it made me reconsider the entire story. I love when that happens. And so I wrote a million new sentences to get those last two. The story was eventually published as “Little Dog” in “The Journal of Compressed Arts,” edited by Randall Brown (another great flash writer). I talk about process and revision via their “Decompress” section linked just below the story.

If you sit long enough, you can wait out just about anything. I’ve learned this trick. It’s the closest thing to magic I know. Silence. A magic wand in reverse. Take back, take back, take back. And then you’re sitting alone, like you’ve wanted to be in the first place, and little flakes of snow flitter down outside the window. –“The World, Floating” –Sherrie Flick

DAVIDSON: Couples, singles. Duo, solo. Together, alone. The collection’s final stories in the section titled “Whiskey” are comprised of women with or without men. “Winter Storm” is imbued with mood, Evelyn and her two Manhattans alone in a cocktail bar on a snowy night; “The World, Floating,” also swept with snow, traces a morning of separation and possible reconciliation; and “Forever” tells of soul mates who remain friends, one married, one single and wishing for the togetherness she’ll never have. What of these lives fascinates and calls to you?

FLICK: Oh, I know. There are a ton of lonely women in this book. I’m not a particularly lonely person, but there’s a core to me, to my creative self, that loves solitude. I’m not sure why I’m so interested in loneliness, but I am. What do people do to leave their lives—even if just for a night? It’s a kind of escape, whether it’s physical or just in a character’s head. My stories are quiet in that way, feminine I guess. If you read them quickly you could say: nothing happens. But I think the most profound human moments are these single moments of quiet realization.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor