Timeless & Changing Vietnam:

An Interview with Catherine Karnow

by Karin Cecile Davidson

Catherine Karnow, a visionary photographer for National Geographic, Smithsonian, GEO, and other international publications, as well as a teacher of worldwide photography workshops, continues the artistic legacy of her father, Stanley Karnow, acclaimed journalist and author of the book and television series, “Vietnam: A History.” While she has witnessed the world via camera lens, Vietnam is the focus of her exhibition and book, “Vietnam: 25 Years Documenting a Changing Country.” Her photographs of the people of Vietnam, documenting the country’s sweeping changes between 1990 and 2014, are breathtaking, emotional portraits of Vietnamese lives: the “Woman on the Train,” the “Doi Moi” economic policies and the Viet Kieu culture, the “Funeral Procession of General Giap,” and the legacies of “the American War” captured in the faces of Amerasians and victims of Agent Orange. From these portraits and landscapes, an understanding of the photographer’s deeply personal relationship with Vietnam comes forth in rich, vital, and textured layers.

Catherine Karnow, a visionary photographer for National Geographic, Smithsonian, GEO, and other international publications, as well as a teacher of worldwide photography workshops, continues the artistic legacy of her father, Stanley Karnow, acclaimed journalist and author of the book and television series, “Vietnam: A History.” While she has witnessed the world via camera lens, Vietnam is the focus of her exhibition and book, “Vietnam: 25 Years Documenting a Changing Country.” Her photographs of the people of Vietnam, documenting the country’s sweeping changes between 1990 and 2014, are breathtaking, emotional portraits of Vietnamese lives: the “Woman on the Train,” the “Doi Moi” economic policies and the Viet Kieu culture, the “Funeral Procession of General Giap,” and the legacies of “the American War” captured in the faces of Amerasians and victims of Agent Orange. From these portraits and landscapes, an understanding of the photographer’s deeply personal relationship with Vietnam comes forth in rich, vital, and textured layers.

§

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: The word “legacy” comes to mind when acknowledging your father’s writing, your photographs, and the place that inspired both. In “Following Destiny,” an introductory section of your book, “Vietnam: 25 Years Documenting a Changing Country,” author Andrew Lam writes of the Vietnamese saying, “cha truyen con noi,” which translates to “Father transmits, child progresses,” in terms of “the Vietnamese understanding of how legacies—be it a profession, passion, or family tradition—can be passed down, as if fated, through the generations.”

Catherine, tell us how this understanding relates to your father’s work and now yours.

CATHERINE KARNOW: During the 1960s, when I was a child growing up in Hong Kong, my father reported on the Vietnam War, but I don’t remember talking to him about Vietnam. Even after we left Hong Kong, and my father continued reporting, culminating in writing his seminal book on Vietnam, I don’t recall our talking that much about the country all the years before my first trip. In the ’90s we had the opportunity to work together on a story for Islands magazine on Halong Bay, and then a story on New Vietnam for Smithsonian. In the years that he was alive and I was working on other assignments or my own work, he loved to hear my stories and anecdotes from Vietnam. He often said, “You are carrying on my legacy.” In fact, I realized I understood and knew today’s Vietnam better than my father.

DAVIDSON: In the photographs of your early years in Vietnam, there is an emotional depth and a kind of longing in the faces of your subjects. Would you tell us the stories of “Hồ Chí Minh’s Personal Sculptor” and “The Woman on the Train”?

KARNOW: In 1990 I spent July in Vietnam. It was my first trip and I met all sorts of people, illustrious and ordinary, including Hồ Chí Minh’s personal sculptor, Diệp Minh Châu. He told me about how he came to know HCM. I remember his telling me that as an artist, he had created a painting with the blood of his finger. The piece depicted HCM surrounded by children, a way HCM was often shown. Using the blood of his finger was Diệp Minh Châu’s way of showing his devotion to HCM. He had the painting delivered to Ho, who was living in the forest at the time, somewhere in Northern Vietnam. Ho was so moved that he asked the sculptor to come live with him in the forest, which he did for many years. Indeed, most of the busts and sculptures of HCM in Vietnam were made by Diệp Minh Châu. Chau told me that Hồ Chí Minh’s hand, when you shook it, felt like a satin glove, supple and silky. But if you were not an intimate, it felt like an iron fist. This really sums up the character of Hồ Chí Minh.

That same year I took the Saigon-Hanoi Train, called the Reunification Express. In 1975, when Vietnam reopened its borders, the train, in a sense, reunified the country. At that time, the train was filthy, and hot, and moved so slowly at times that you could have gotten out and walked faster. Taking pictures kept me distracted from the misery of the situation. For days I walked up and down the train, meeting people and photographing them, sometimes with my Vietnamese-Australian friend who acted as translator.

Finally, on the third day, we approached the mountains in central Vietnam. The train moved even more slowly as it wound around to climb the steep track. I knew it would be a good shot when the train started to come down; you would see the green mountains and the track curving behind. I went up to the front of the train, looking for a way to photograph people at the window and see the rest of the train curving behind. I came upon a young mother with her children. As my translator friend was not with me, I gestured a request for permission to photograph the woman. I found her beautiful and photographed her leaning out the window, a far-away look in her eyes.

Interestingly, one of the photographs I took was published on the cover of the “Lonely Planet Guide to Vietnam.” A few years ago, I was contacted by a Rosalyn Vu, the daughter of the woman in the photo, though not one of the children pictured. She said that she and her mother had seen the photo on the Lonely Planet guide and always wondered how to get in touch with the photographer. I was astonished and delighted to hear from them. Just to be sure it was the same person, I asked Rosalyn to send me a shot of her mother now. Sure enough, it was the same woman, twenty years later. We were overjoyed to reconnect.

That look of emotional depth and a sense of longing you see in these portraits and others isn’t something I can easily explain. Indeed, it is a mystery to me why certain cultures, certain people, even certain individuals anywhere seem to have this look. I think that in Vietnam, there is a collective sense of nostalgia and loss, despite that the Vietnamese are, and have always been, a people who look forward and don’t dwell on the past. Nevertheless, they are survivors of many wars and tragedies. They are an emotional people as well. Perhaps this is what I am able to capture in these expressions. Bear in mind two points. One, it is true that every photograph is a self-portrait. And that when you photograph someone, they will mirror you, the way they perceive you to be and feel. So perhaps it is also my own sense of loss and longing that is captured in their faces.

DAVIDSON: Your images in the 1990s Đổi Mới period of economic reform and today’s New Vietnam reveal how vastly the country has changed in the past two decades. Is there an experience in relation to your work in Vietnam that stands out to you when reflecting on this period?

KARNOW: The Đổi Mới period of the mid ’90s was a time quite different than today’s Vietnam. A few years ago, I spent a Saturday with a Vietnamese family in the upscale suburbs outside Saigon. The little girl, Betty, had a tutor over to both help her with her studies and teach her piano and art. Her father’s dream was for Betty to go to an East Coast American prep school like Andover or Exeter. At the same time, he had traditional Vietnamese aspirations of owning two more houses in District 7, one for Betty and one for her brother, when they grow up. Family is everything in Vietnam and staying together is paramount. Most married couples live with the husband’s parents. When you ask a Vietnamese where he is from, he will tell you not where he was born, but where his ancestors were born.

Although I was taken aback by Betty’s house, when I accompanied her to a play date later that afternoon, I was really floored. The house we visited was huge and unwieldy, as if the inhabitants didn’t understand what to do with all their space. They would only let me photograph for five minutes in the little girl’s bedroom. I remember when I saw this bedroom for the first time, my jaw dropped. I didn’t feel like I was in Vietnam. In fact, at both Betty’s house and her friend’s I felt like I was in Orange County, where, by the way, many Vietnamese settled after escaping Vietnam after the war.

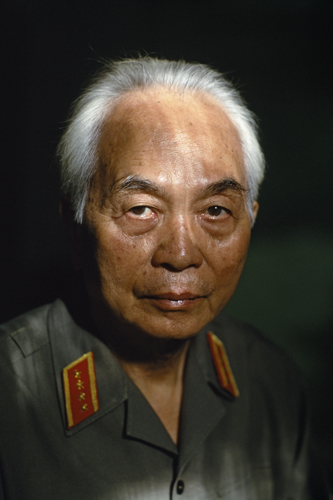

DAVIDSON: General Giap is renowned for his military victory against the French in 1954, winning Vietnam’s independence, and against the Americans in 1975, when the Communists overtook South Vietnam. Tell us how you met General Giap and his family, as well as your reaction to seeing hundreds of Vietnamese citizens holding up copies of your 1994 portrait of the general during his funeral procession in 2013.

KARNOW: My friendship with General Giap and his family began in July of 1990. I knew General Giap through my father, who had interviewed him for The New York Times in 1990. I loved that the French called him the “snow-covered volcano” for his white hair and fiery temperament; I wanted to somehow depict that in a photograph.

That hot July day, we sipped tea in the living room, as I strained to figure out where I could photograph the General. I needed good natural light, but the house was dark and austere, dim fluorescent bulbs barely illuminating our faces. I asked if I could look around and the General waved me permission to do as I wished. His handlers grew agitated and followed me apprehensively as I walked into the dining room and then the kitchen. Then I saw it. There was a ray of light coming down onto the back stairs.

I asked the General to come to the stairwell. This man, famous for his will of steel, followed me amiably to the spot where the ray of sun beamed down. He agreed to sit on a lower stair and look up at me so the light shone in his eyes and illuminated his snow-white hair. It was a very unorthodox way to photograph such a powerful man. But clearly he admired my tenacity and perseverance. He liked the photograph as well, and so our friendship began on that day.

In 1994 I was invited by General Giap to be the only western journalist to accompany him privately to Điện Biên Phủ. I had been at his house a few days before, photographing him and having dinner with the family, when he leaned over and whispered the invitation in my ear, telling me not to tell anyone. Journalists and photographers had been gathering for days in Hanoi, wondering if the General would be visiting Điện Biên Phủ for the 40th anniversary of the battle. Now here he was inviting me to go with him privately, the week before the actual anniversary date of May 7th.

I was anxious as we flew from Hanoi toward Điện Biên Phủ. I knew that for me to get the best photos, I needed to be with him at all times. General Giap would be visiting not just the battleground and a war cemetery, he would be returning for the first time in 40 years to Mường Phăng, the secret encampment in the forest, where he had hidden out during the months that led up to the battle, and from where he plotted the now-famous strategy of Điện Biên Phủ.

General Giap would be going to Mường Phăng by helicopter, but I would go by jeep—a rough, six-hour trek over rocky terrain and potholed roads. I was told we would be there in the early afternoon and that the General would arrive at about the same time.

There were hundreds of people gathered to await the arrival of the General by helicopter. Expecting him to land at any moment, I made sure my cameras were loaded with film and I was in a good shooting position. Minutes and hours passed. I had nothing to eat. There was only warm, flat orange soda to drink. It was impossibly hot and the sun was relentless.

Finally, there was a buzz in the sky and we saw the great bird coming toward us. The people ran toward the helicopter as it landed and the General emerged waving to the crowd. We began the long trek up the mountain to visit the secret hideaway in the forest. For a man of 83, the General was in excellent shape. As we approached the spot where he had lived for the many months leading up to the final battle, villagers greeted him with great reverence and joy. He hadn’t been seen some in 40 years.

In moments we were in the tiny hut, the exact same hut where he had plotted the strategy of the battle. On the wall was a replica of the same map he and his commanders had used forty years ago. Giap recounted his memories of those days spent in the hut. He said, “My only regret is that the same commanders who were with me that day are no longer with us and cannot be here today.”

For me, it was momentous to be in that hut in the middle of the jungle of Northern Vietnam, hundreds of miles from anywhere, witnessing a living legend recall his personal moment in history.

Since then, my friendship with his family has grown. In October of 2013, the General died and I flew straight to Vietnam for the funeral, which took place in the imposing State Funeral House. The following day was the funeral procession, which wound through the streets of Hanoi on the way to the airport, where the coffin was placed in a Vietnam Airlines jet with great ceremony and reverence. Later I would learn that thousands of people had come to Hanoi from all over Vietnam. I joined the family as we flew to Quảng Bình Province for the burial.

We landed in Quảng Bình Province, and the funeral procession wound slowly through the countryside. I was astounded to see that many people were holding up my portrait of the General, one I had taken in 1994. It was a photo that his wife had asked me to take, just for her to have. I shot a few frames, then mailed them to her a few weeks later. Little did I know it would be published on many book covers and in newspapers, and now here in the middle of a country province I had never visited, I was seeing hundreds of people lining the road, holding up my photograph. I was deeply moved, sensing my place of belonging here in this country so far from my own.

When we arrived at the burial site, there were hundreds of people, and I knew I had to stay close to the family to avoid being separated. The coffin was brought up to the burial site and then we waited. Auspiciously, the time to lower the coffin had to be right. We waited. The family stood close together, with tears in their eyes. The little grandchildren were perfectly behaved. I wanted to stay at a respectful distance from them, but whenever I stepped back, a guard, not noticing that I was an invited guest, would try to pull me away from the scene altogether. A family member would notice and motion that I was a friend. As a result, I ended up standing right beside them the entire time.

The coffin was lowered into the ground and, as day became night, the people streamed up to pay tribute to the General. They would come all day and all night for days, even weeks. For me, it was a great honor. I was raw with emotion myself. I knew my father would have loved to hear this story, and though I missed him, I felt surrounded by the love of the General’s family. I would give them the photographs as a way to say thank you, and for them to have memories of this painful yet beautiful time.

DAVIDSON: Lasting legacies of the war in Vietnam—the war which the Vietnamese call the American War—are still present in the genetic disaster of Agent Orange and the plight of the unwanted, “children of the dust” Amerasians. Catherine, how has your involvement and documentation of these populations brought awareness, especially in terms of the U.S. recognizing responsibility and in lieu of the difficulties that still remain?

KARNOW: During the Vietnam War, the U.S. military sprayed some 12 million gallons of the Agent Orange defoliant over parts of Vietnam to destroy the foliage so the enemy would have no cover. Now, almost four decades later, the toxic herbicide continues to have a devastating effect on thousands of Vietnamese people. Passed down genetically, Agent Orange has caused various diseases and horrific deformities in three generations of Vietnamese families. Most people have no idea that in Vietnam today there are babies born every day with this disease. There is no test, and there is no cure.

In July of 2010, I spent time with two families in Danang, Central Vietnam, the site of one of the busiest military bases during the war. Working with the NGO, Children of Vietnam, I spent time with nine-year-old Nguyen Thi Ly. Ly suffers from respiratory illnesses and a sunken chest cavity. Her mother is also affected.

As an American, I feel a responsibility to expose this horrifying problem and to help bring about real change. I know that we can bring much more support than now exists. In a more immediate way, I can see the way that my photographs bring a sense of affirmation to these individuals who are suffering in illness and isolation.

In 2014 Senator Patrick Leahy visited an Agent Orange family I photographed. His visit signified for the first time the U.S. government’s official acknowledgment of the need for humanitarian aid for Agent Orange victims.

Children of Vietnam helps take care of children and families with Agent Orange afflictions.

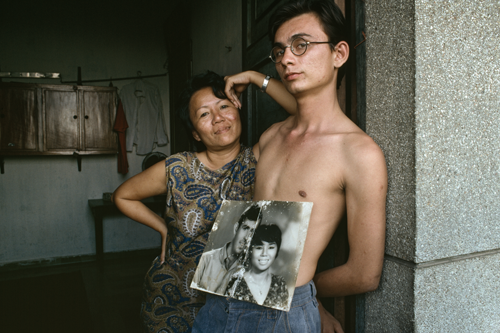

Another unfortunate legacy of the Vietnam War is the story of the Amerasians, the offspring of the American soldiers or civilians and Vietnamese women during the war. No one can pinpoint just how many Amerasians there were. Figures range from 70,000–100,000. They were rejected for many reasons: being bi-racial, how their mothers were thought to be prostitutes, that they symbolized the enemy. In 1987, the U.S. finally admitted responsibility and started to allow Amerasians and their families to come to the U.S.

In today’s Vietnam, there remain very few Amerasians; those left still harbor a dream to come to the U.S.

For Amerasians, there is always this search for the father. For Smithsonian magazine, I photographed Phuong Thuy, an Amerasian whose dream was to be able to leave Vietnam and find her father. When the magazine published a full-page portrait of her, she took it to the U.S. Consulate who gave her permission to move with her family to the U.S. Miraculously, she found her father and they are now joyfully reunited. However, neither wants to be DNA-tested, perhaps to preserve their dream of being father and daughter.

DAVIDSON: There is a final section in “Vietnam: 25 Years Documenting a Changing Country” called “Timeless Vietnam,” wherein you’ve captured longstanding traditions as well as the creativity, powerlessness, and beauty of the Vietnamese. There is a meditative quality to these photographs, one that calls for reflection. In “Bride in Dalat” and “Barber,” in your memory of shooting these photographs and in studying them now, what is most striking and essential?

KARNOW: I suppose it is despite all the changes in Vietnam, one not only sees these timeless scenes, but I sense that same sense of nostalgia and sadness. I learned a few years ago that there is a word, buồn, and it means finding beauty in sadness.

DAVIDSON: Vietnam, relationships, belonging. Past, present, future. Do you find a timelessness in your connection to Vietnam?

KARNOW: I am especially proud of my Vietnam Photo Workshop which I hold each October. In that, I can share the Vietnam I have come to know so well: my own friends, people in my photographs who have become friends, and a taste of the many adventures I have had. The most moving day is no doubt the one we spend with Agent Orange families in Danang. My guests are able to spend quality time with families in their homes with the time to talk and listen. After my workshop last year, one guest donated enough money for a family to have a new kitchen floor, important to the mother, as her handicapped boys have to move about on the floor. Another guest made a beautiful book of her photographs to send to the family she photographed. And yet another guest gave several fundraising presentations of the students’ photographs to Silicon Valley audiences who, in turn, donated to help better the lives of these families with children affected by diseases associated with Agent Orange. And so my real pride now is to share Vietnam with others, both through my book, my presentations, and through my Photo Workshops.

Each time I return to Vietnam, I find myself drawn deeper into the country and its people. I sometimes fear that the “magic” —my deep love and excitement and curiosity I feel—will have somehow disappeared. But in fact, my love only grows and it is perhaps because we do have this long relationship. Now we have been together for more than 26 years and so many places have special memories for me. I have had so many experiences and know so many people that my own time there is only richer with each visit.

“Vietnam: 25 Years Documenting a Changing Country” is available to purchase directly from Catherine Karnow (catherinekarnow [at] yahoo [dot] com) and at Book Passage in Corte Madera, Calif. Information about her photography workshops in Vietnam and Umbria is available via her email and website as well.

Karin C. Davidson, Interviews Editor