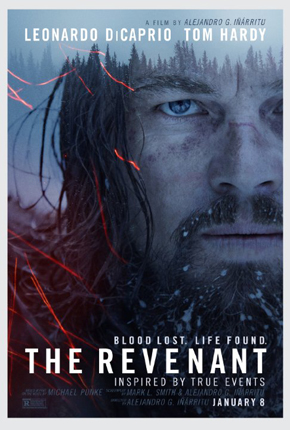

‘The Revenant’

And the Power of Sympathy

Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu, “The Revenant”

Twentieth Century Fox

2015, 156 minutes

“To call a story a true story is an insult to both art and truth,” Vladimir Nabokov wrote in his essay “Good Readers and Good Writers.” “The Revenant” somehow manages to insult neither.

“To call a story a true story is an insult to both art and truth,” Vladimir Nabokov wrote in his essay “Good Readers and Good Writers.” “The Revenant” somehow manages to insult neither.

So far as truth goes, there is no mention of the true story, not even a what-happened-next slide show as a conclusion; “The Revenant,” as the movie poster relays, only claims to be “inspired by true events.”

The screenplay was cowritten by Mark L. Smith and director Alejandro G. Iñárritu, who take plenty of liberty with the story, loosely adapting it from the novel by Michael Punke about a frontiersman named Hugh Glass. The story is murky, both historically and geographically (set in the early 19th century, somewhere in the Rockies), but this haziness mingles with the almost dreamlike and miasmatic fog that settles over the events that transpire in the heart of the wilderness. Nonetheless, does the “true story” of Hugh Glass matter? Could that story actually be told? Along his journey for revenge, we feel sympathy not for the real Hugh Glass who lived however many years ago but for the Hugh Glass of this story. Shouldn’t a fictional story evoke just as much emotion as a true one? Isn’t a story labeled “true” nearly as fictional as one labeled “fictional”? This is the balance that “The Revenant” manages: it insults neither art nor truth.

After the Academy Award–winning “Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance),” this is the second major English-language film by director Alejandro G. Iñárritu, cranked out roughly just one year later. Iñárritu imbues this film with the same cinematographic magic, striking visuals, and dreamlike captivation, but in a context that could not be further from that of his previous films. Alongside masterful cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, Iñárritu forges a visual work of long, sweeping scenes (though not even close to that of “Birdman”) and stunning landscapes that capture both the brutality and beauty of the Great North American West. Despite the phantasmagoric presence that saturates the film, a stark, uncompromising consciousness governs every aspect of the film’s production. Unlike any other mainstream American moviemaker, Iñárritu again surprised and captivated Hollywood, earning himself two Golden Globe Awards for Best Motion Picture-Drama and Best Director, as well as a basketful of Oscar Nominations.

Of course, the most famed scene in the film is the minutes-long struggle between lead actor Leonardo DiCaprio’s character, Hugh Glass, and a massive Grizzly Bear. DiCaprio called it a “great cinematic achievement,” and as an audience member, one can’t help but to lift the veil of suspended disbelief and wonder exactly how this scene was made. But the movie-magic that raised a new widespread bearphobia is but a relatively small tidbit of the grand scale of the production.

In an interview with ScreenSlam, DiCaprio spoke about the extreme difficulties of making this movie, venturing, “Challenge anyone in this movie to say this wasn’t the hardest thing we’ve all ever done.” The sub-zero temperatures, the shifting landscape, the elements—all contributed to the difficulty of this production. The challenges—from the cruel conditions to the creation of the bear—command attention, but there is no doubt it paid off in the form of artistic output.

Not only has “The Bear Scene” been greeted with high acclaim but so has DiCaprio’s performance as Hugh Glass, earning DiCaprio a Golden Globe for Best Performance as an Actor and a nomination for his long-sought Oscar for Actor in a Leading Role. [Editor’s Note: DiCaprio has since won an Oscar for Best Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role]. Though DiCaprio speaks mostly in raspy grunts, he manages to produce an extremely moving performance; when he does offer a rare line (and many of those in a Native American language called Arikara) it’s gut-punching. Possibly the most haunting of these lines DiCaprio delivers in a hoarse whisper, lit Vermeer-esque through a foggy window: “I ain’t afraid to die anymore—I done it already.” Through those labored breaths, though, he manages to convey extreme emotion. This was a struggle that DiCaprio consciously faced, along with the difficulty of progressing plot and conveying thoughts without the tool of language. Facial expression and breath seem to have come to the forefront as methods of communication for DiCaprio, culminating on the last scene, where in its final moments, he looks desperately into the camera—at us—and breathes.

In “The Revenant,” breath is a deeply entwined and prominent symbol, a signal of life, the will to live. Frequently throughout the film, particularly when Glass is physically struggling (hardly metonymically), the theater is filled only with the sound of his gasps and the wind sonically mixing, muddled together in a lump of pulsing airy noise. Also, many times throughout the movie, the camera lens fogs up as someone breathes onto it. The effect is unique, and makes the thematic reoccurrence even more prominent, exhibiting multiple characters—even the bear—breathing the stuff of life, proving their will to survive.

Nabokov, in the same essay, lists three facets of a great writer: magic, story, and lesson. In “The Revenant,” the story is there (laced with subtle symmetries and rife with subtext) and, God knows, the magic is too. So much as I can tell, the lesson is something like this: Yes, “The Revenant” is a revenge plot—a story of anger and passion, pure will, and the resiliency of the human spirit; but it isn’t so much a simple revenge narrative as it is a story of compassion and sympathy amidst the boldness of nature. And this sympathy comes two ways: from within the story and from without. As you witness the kindness of a lonesome Native American, you realize your own sympathy for Hugh Glass, for the Native Americans, even for Tom Hardy’s poor scalped villain, as despicable as he is. Maybe this is why the movie is so hard to watch—you continually find yourself feeling as if you’re in a dentist’s chair, slightly reclined, every muscle tensed, breath held—not only from the suspense but from the sheer force of the sympathy you exert (and you almost have no choice but to exert it). The power of sympathy looms over each of the 156 minutes. And isn’t that the bridge that connects any audience to a story, now or then, here or there, truth or fiction?

It is easy to think of such a story as entirely un-relatable, irrelevant. But the story of sympathy, will to survive, near-death perspective, destruction of nature, compassion, anger, love, grief, suffering, and the human spirit is everlasting.