Magical Realism Comes to Idaho

Reviewed by Ron McFarland

Keith Lee Morris, “Travelers Rest”

Little, Brown & Co.

2016, 368 pages, hardcover, $27.00

Keith Lee Morris’s third novel “Travelers Rest” might be aptly described as “serious fantasy” or “magical realism” due to the credibly realistic set of events and characters disturbed by preternatural phenomena. Morris’s previous books include two collections of short stories, “The Best Seats in the House” (University of Nevada Press 2004) and “Call It What You Want” (Tin House Books 2010) and two novels, “The Greyhound God” (UN Press 2003) and “The Dart League King” (Tin House 2008). Travelers Rest is his first book to be released by a major publisher. From online comments on his previous books, it would seem this Clemson University professor of creative writing has acquired an enthusiastic readership. “The Dart League King,” for example, has garnered 429 ratings and 75 reviews on goodreads.com (3.76 stars—“whatever that means,” one might be inclined to say). Although, I am not a great fan of other fantasy genres, like Stephen King, for instance, Morris’ novel attracts me.

Keith Lee Morris’s third novel “Travelers Rest” might be aptly described as “serious fantasy” or “magical realism” due to the credibly realistic set of events and characters disturbed by preternatural phenomena. Morris’s previous books include two collections of short stories, “The Best Seats in the House” (University of Nevada Press 2004) and “Call It What You Want” (Tin House Books 2010) and two novels, “The Greyhound God” (UN Press 2003) and “The Dart League King” (Tin House 2008). Travelers Rest is his first book to be released by a major publisher. From online comments on his previous books, it would seem this Clemson University professor of creative writing has acquired an enthusiastic readership. “The Dart League King,” for example, has garnered 429 ratings and 75 reviews on goodreads.com (3.76 stars—“whatever that means,” one might be inclined to say). Although, I am not a great fan of other fantasy genres, like Stephen King, for instance, Morris’ novel attracts me.

Divided into four parts, each headed by an epigraph drawn from Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past”, the novel owes some of its quick pace to the fact that it is comprised of forty-seven short chapters, the lengthiest of which runs no more than twenty pages. Action oscillates among the four primary characters: Anthony (Tonio) Addison, an anthropologist somewhat distant from his wife, but slightly obsessed with his son; Julia Addison, the wife-and-mother who seems uncertain about her capacity to fulfill either role adequately; Dewey, their precocious ten-year-old son, who often seems more in command of the bizarre circumstances than any of the adults; Robbie, Tonio’s wayward brother and lost soul, who suffers from drug and alcohol addiction and who is driven from Seattle to Charleston, South Carolina, where he will enter rehab. Morris apportions the chapters so that the principal characters get from nine to thirteen apiece, with the result that we acquire an evolving understanding of each of them at a carefully controlled pace.

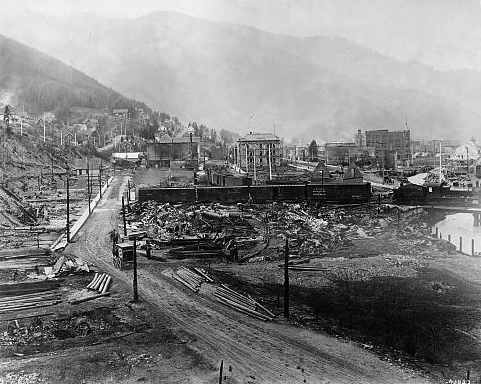

As in much of Morris’s fiction, the action takes place mostly in the Idaho panhandle, but in this novel we do not encounter his familiar hometown of Sandpoint, which is readily detectable in several of his stories and which appears under the name of Garnet Lake in “The Dart League King.” This narrative is set in a former mining town called Good Luck, reminiscent of Wallace, heart of the silver mining boom in the Idaho panhandle during the 1880s. The family reaches in the midst of a snowstorm by turning off the interstate (I-90) at Julia’s suggestion. Predictably, the town’s moniker proves ironic, as they find themselves stranded in a dilapidated hotel (Travelers Rest) during what turns out to be an incessant snowfall—the snow falls heavily throughout the novel, except for the last half dozen or so pages.

Readers may be forgiven if they momentarily lapse into memories of the 1993 comedy, “Groundhog Day,” starring Bill Murray and Andie MacDowell, but this will prove to be no comedy. Quickly the four family members become separated from one another, and for “reasons” that only gradually become apparent and that transcend any rational measures, they must work through the complications and failures of their lives.

On the other hand, the haunting story that unfolds comes across as more intriguing than frightening. The silver mine began operation in 1878 and was appropriately called, as we learn The Dream Mine. Carved over the entrance is the statement, “All Our Dreams Are True.” As Hugh and Lorraine, the couple who run the town’s diner and who act as surrogate parents, inform Dewey, “people get drawn here.” The town has “a magnetic quality.” Those who are drawn off the interstate and into this town are “people who are trying to remember something or maybe they want to change something they regret.” This applies clearly enough to the three adults of the Addison family, as we come to realize. Readers are likely to feel some degree of anxiety for Dewey, but Morris equips him with the intelligence and perceptivity of a Henry James child, so we rarely, if ever, doubt that he will come out of it well enough. The danger for him is that he will become a “souvenir,” that he will be reduced to something of a trinket, a memento. Accordingly, the thrust of the plot has to do with how Dewey can negotiate his escape.

“Think of a place where everything is opposite,” Robbie’s new-found girlfriend Stephanie tells him: “The past is the future, and the future is the past. Dreams are reality.” Robbie says he “gets it.” But she then elaborates. He must now think of “a place where everything is its opposite but also still itself at the same time.” Like Hugh explaining the weird circumstances to Dewey, Stephanie explains that people “came here because there was something they had to see.” The permanent residents of this nowhere town “need” to be there. In some ways, the novel offers us a metaphor of life in small, remote towns where people cannot seem to get away. Morris has visited this phenomenon in his stories and other novels, many of which feature characters who want to get out but cannot seem to do so.

Some have described Morris’s writing as “literary fiction,” and this novel is no exception, as the epigraphs out of Proust would suggest. But Morris’s style and voice are almost disarmingly easy, conversational, and comfortable. Some vestiges of his earlier protagonists, drug-ridden and profane, obscene, vulgar, more apt to get themselves into trouble than out of it, are lodged in the errant brother Robbie, but in various ways this is a breakout novel for Keith Lee Morris. His characters are easier to like or to empathize with than they are in such novels as “The Dart League King” and “The Greyhound God.” This novel touches casually on profound issues of identity, the nature of time and memory, parental responsibility and love, and significantly, justice.

Ron McFarland teaches at the University of Idaho. His most recent book is “Appropriating Hemingway: Using Him as a Fictional Character” (2015). His biography of Lt. Col. Edward J. Steptoe (1815-1865) will be published next year by McFarland & Co. (no relation). His current projects include a chapbook of poems related to the Civil War and a book of poetry.

Ron McFarland teaches at the University of Idaho. His most recent book is “Appropriating Hemingway: Using Him as a Fictional Character” (2015). His biography of Lt. Col. Edward J. Steptoe (1815-1865) will be published next year by McFarland & Co. (no relation). His current projects include a chapbook of poems related to the Civil War and a book of poetry.

0 comments on “Reviews: Keith Lee Morris”