Coming From Age:

On Ryckman’s Roaring

‘Twenty-Something’

Reviewed by Doug Horolez

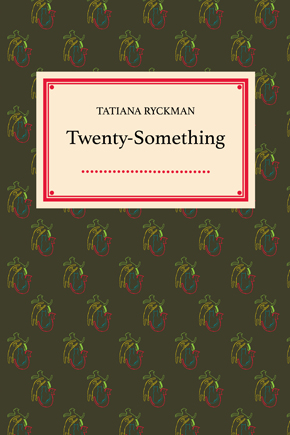

Tatiana Ryckman, “Twenty-Something”

ELJ Publications

2014, 28 pages, softcover, $13

At twenty-eight pages, Tatiana Ryckman’s “Twenty-Something” is a slim collection of significant stories.

At twenty-eight pages, Tatiana Ryckman’s “Twenty-Something” is a slim collection of significant stories.

The Dover Thrift Edition design of the collection asks a reader to take the frivolity and frenetic dementia of our twenties as a serious literary subject. Ryckman delivers with fifteen flash-y fictions that navigate the still young and misshapen relationships of our tumultuous twenties, as well as the disillusionment over adulthood’s unfulfilled expectation of clarity and/or stability. Refreshingly, these stories focus away from the yo-yo TV melodrama, instead highlighting the often-painful lessons learned along the way, like the best coming-from-age stories.

Coming-from-age-story:

A story that follows a protagonist from adulthood to truce-with-adulthood. These stories tend to emphasize internal monologue and dialogue over dramatic action, and are often set in the character’s fantastic or fatal daydreams, awkward and/or (self)deprecating conversations, and various lovers’ bedrooms. The subjects of coming-from-age stories are typically educated, upper middle-class bohemians in their mid to late twenties. It especially focuses on the protagonist’s psychological growth, sometimes at the cost of their (perceived) moral values, and thus character development is central.

Several of these stories dramatize the desire to achieve wholeness (psychological stability/independence) while engaged in relationships that demand giving pieces of one’s self. For instance, in stories like “E.T. + Richard Burton = 4EVER,” in which Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor go out on a date whilst she’s still married to someone else, sex is portrayed as a means of union, and its failure to bring the many couples in this collection closer hints that romantic relationships themselves cannot complete a person and bring about the union-of-being each seeks.

If the candid protagonists of “Twenty-Something” are irreverent in discussing their sex lives and relationships, it’s because each is in transition, requiring norms to be temporarily ignored in hopes of developing into a person of value, authenticity, and worthy enough of her own esteem. As in the story “All the Reasons I Love You, Even Though Life is Fleeting and You’ll Just Die and Rot Anyway,” in which two people take turns probing each other while pretending to be asleep or dead, we are reminded—as they first discover—that wholeness comes from elsewhere. But where? We are left here with the narrator waiting for an answer, but ready.

“Twenty-Something” best portrays youthful vulnerability and the anxiety of being slight forever, a thing in perpetual development without arrival. With grace, most of these stories finish with some ground made, less as a revelation coming into focus, so much as an identity taking form unapologetically. This form donned by the female protagonists curiously dips into gender bending in stories like “Boy’s Club” and the title story, “Twenty-Something”:

She thinks her muscles are swelling in her skin, and she is becoming stronger, larger. She thinks this must be what it’s like to be a man, the solid fearless wearing of one’s own skin, and she grows into the feeling. Expands into it like a water balloon. She imagines walking to her car at night with confidence, yelling from the open window at men on their way to the grocery store, the freedom of unquestioned safety.

At the same time, these stories are conscious of patriarchy and illustrate common displays of ignorance, violence, and harassment from the female protagonists’ male counterparts. Men are most often portrayed as obstacles of their coming into something-ness, making gender impossible to ignore in this collection.

At the same time, these stories are conscious of patriarchy and illustrate common displays of ignorance, violence, and harassment from the female protagonists’ male counterparts. Men are most often portrayed as obstacles of their coming into something-ness, making gender impossible to ignore in this collection.

Though the content grapples with big ideas and feelings, the writing itself is fresh and inventive. This owes largely to fantastic moments of escape from the mundane: stories that take place beside a sea full of “mewling kittens” or within a slice of pie. These leaps are accomplished through the narrative logic of poetry. The mention of a notable detail, like the Heat Bringer’s potent, flaming ejaculate in “Heat Bringer,” seems to summon one of his children on stage playing the drums, which then sparks a confrontation between father and son over conga lines and paternal embarrassment, and suddenly readers find themselves in the fiery belly of the story.

At the collection’s end, the search for identity and meaning returns to childhood among aging parents and grandparents. These stories read like flashbacks from a much larger work, exploring the narrator’s Czech heritage, coping with death and the undulating current of time. Much like isolated flashbacks, however, the dramatic tension feels let out of the tires and the narrative drive lumbers to the finish line, and I found myself wanting more. Or perhaps that was entirely the point—arriving at resignation to life’s ups and downs, and Ryckman has recreated the illusion of a steadier course because our minds simply have adjusted to the bumpiness?

Ultimately, Ryckman’s “Twenty-Something” defines the mythos of one’s twenties as being a specific existential trip—the desire and struggle to be something. This is never more poignant or exciting than in the title story, which depicts the life of Clarice, cubicle jockey by day and nude model by night:

Will she still work the same job she’s promised herself to quit for a year? Will the 2020s, too, be called The 20s? As she takes a long drink, she feels suddenly divided between the person she’s known herself to be and the person she’s wary of becoming. She feels herself growing opposing poles that separate the part of her that is made up of her own ideas about that decade and the roar of it—that is, her own imagined history of anything—and the vacant, waiting future.

Of course we don’t get the aftermath, the Great Depression, here—and thank goodness. Ryckman characterizes the best and worst decade of your life while avoiding the clichés that turn engaging stories into pity parties with room for one. It’s the looming threat of collapse and potential roar of freedom that pervade these stories and allow “Twenty-Something” to end in a startling breath, a successful break in the incessant loop of self-reflection on our search for meaning. This break reads like wisdom and will leave a reader eager to hear what Ryckman says next.

0 comments on “Reviews: Twenty-Something”