Erasure

by Howard Skrill

The last time that I visited the World Trade Center was probably in August, 2001. I read a classified ad calling for docents to work at the African Burial Ground National Monument that was being constructed nearby as a part of the huge federal office complex that was eventually named for former New York Congressman, Ted Weiss. I knew Ted Weiss. His family and my own have a history. That is a tale for another day.

For the past four years, I have been working on a series of drawings, the “Anna Pierrepont Series.” The “Anna Pierrepont Series” consists of my wandering throughout New York City and sometimes elsewhere, trailing a blue whole foods bag and making plein air drawings of public statuary. In early Fall 2014, my wife was out of town visiting her father. I was running an errand in midtown Manhattan. It was a fairly nice day, and I walked to another errand in Greenwich Village and a third in Tribeca. I continued walking over the Brooklyn Bridge, towards Brooklyn.

My route took me past the African Burial Ground. I never did docent at the memorial, which in 2001 was under construction and is now open. The memorial is tucked onto on a side street on route to the bridge.

Remains of slave burials were discovered during the construction of the Ted Weiss Federal Building. Following the recuperative, pedagogical impulse that directs memorial construction in the contemporary ethos, the site of the remains was preserved. A museum was established to illuminate the large slave population that lived and died in New York City during Colonial and Post-colonial periods. The African Burial Ground, built around the graveyard, brings to light the existence in New York City of a significant numbers of men, women and children, whose presence here, whether through intent or neglect, had been wiped from collective memory. High School classes I attended a few decades and a mile and a half north of the Ted Weiss building in Manhattan, depicted slavery as a Southern institution that barely tainted New York City. The African Burial Ground gives lie to this narrative.

A lone guard was standing at the site’s open-air front entrance. The museum itself is underground. At the west end of the site, a row of neatly sculpted semi-circular mounds of earth rise from the ground, carefully covered with manicured with grass with the rich color of baseball outfields.

The focus of the “Anna Pierrepont Series” is on drawing of the figurative public monuments. These monuments can be free standing or sculpted onto the facades of buildings. I have wandered New York City for nearly four years to draw these monuments with combinations of oil pastel, oil stick, chalk pastel and colored pencil. Predictably, I have returned repeatedly to draw the monument closest to my home, the Soldiers and Sailors’ Arch. The arch is at the summit of a palisade that slopes upward in an Easterly direction from my house at the bottom of the Palisade. The palisade evens out into Prospect Park.

At the entrance to the park is Grand Army Plaza. The arch stands across a traffic island from the north entrance of the park. The monument was erected in the late 1800s to commemorate the soldiers and sailors of the Union Army during the Civil War.

About a mile and a half south of my home, in Greenwood Cemetery, is another monument celebrating Union soldiers. Four bronze figures flank an obelisk that stands on top of another palisade, which provides ample views of New York Harbor. Upon entering the cemetery through its massive brown sandstone gates on 5th avenue in Sunset Park, I follow Battle Avenue up a gradual incline that tops out at Battle Hill. A concrete stair at the highest point of Battle Hill provides access to the monument. Battle Hill is the site of a major battle in the Battle of Long Island that took place in 1776, four score and a handful of years before the war that was commemorated on the site of Battle Hill. The only reference near battle hill to the Battle of Long Island is a modest plaque hammered into the ground at the hill’s base.

As I roll my bag crammed with art supplies and a folded blue canvas chair from Grand Army Plaza to Battle Hill and points in between, I often pass other plaques commemorating additional battlefields in the Battle of Long Island. About a quarter mile southeast of the Soldiers and Sailors Arch, is a dark bronze plaque inscribed with “Battle Marker of Battle Pass.” The plaque is hammered onto a rock nearing the base of a fairly steep Palisade along the perimeter of Prospect Park’s roadway. The Battle of Long Island was between the armies of Great Britain under the command of General William Howe and armies of the newly established United States of America, commanded by General George Washington.

Civil War monuments were erected at both these sites of Revolutionary War battlefields. These efforts have effectively dimmed the memory of the Battle of Long Island from my own and others’ consciousnesses.

The Revolutionary War killing ground was spread over a broad string of palisades extending from modern Prospect Park to Greenwood Cemetery. Another battlefield is a few blocks from my home at a small stone cottage across the street from my youngest son’s middle school.

The Battle of Long Island, given even the most charitably of interpretations, was a rout for American forces. The British had sailed into New York harbor with a formidable armada of soldiers from the furthest reaches of the vast British Empire. They were further bolstered by German mercenaries. Thousands of soldiers emptied from these ships, marching northward from Gravesend Bay upon a road that eventually became Flatbush Avenue. The British and American armies met in battle in what became in the 1800s, Prospect Park. The Battle of Long Island was the largest military campaign of the Revolutionary War. The Americans eventually were forced out of Brooklyn by Britain’s better-trained, more seasoned military assisted by Hessian Germans in their pay.

Brooklyn would naturally view the Battle of Long Island ambivalently and that ambivalence would carry over into the nature of its commemorations. This ambivalence and avoidance is demonstrated in the Soldiers and Sailors Arch being constructed just north of the site of the one skirmish in the Battle of Long Island and another built directly upon an actual hill where the Battle of Long Island was fought. In contrast to the scattered and modest plaques to the Battle of Long Island are the monumental, dynamic and exultant monuments that Brooklyn constructed to celebrate the Union victory in the Civil War.

Graves of perhaps twenty thousand enslaved individuals were buried in a small plot of land in Lower Manhattan. They were buried even deeper when the ground above their graves was razed to make way for one of the United States’ first department stores. The present day evacuation of the foundation of the Ted Weiss building that now occupies the Southeast corner of Broadway and Duane Street, revealed about 400 of those remains. The site was preserved as a federal monument to New York City’s previously ignored slave legacy.

I have an image in my mind of Osama Bin Laden and his associates sitting in their caves in Afghanistan a few years before 9/11, passing back and forth a picture postcard that was emblazoned “Welcome to New York” in red block letters over an image of the New York skyline. Bin Laden or one of his associates taps the World Trade Center towers rising above from the skyline in the postcard. He looks up to see the rest of the assembled staring at his gesture nodding their approval. On 9/11, the fate of the soldiers from the Battle of Long Island and the slaves interred below a now also erased department stores’ fragrance counters and hand bags, was visited upon over 3,000 people in those two massive steel and glass towers that rise no longer above the New York City skyline.

I attended a reception recently where I had a conversation with a Local Historian about the irony of Civil War monuments built above the killing ground of the Battle of Long Island. She mentioned the huge Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument to 11,500 American prisoners of war murdered on British ships during the Battle of Long Island. This tall monument, visible from New York harbor, occupies yet another high palisade in what is now Fort Greene Park.

A couple of days after the walk that led me past the African Burial Ground, on a what turned out to be a lovely early Fall afternoon, I took the subway to Greenwich Village to draw the Washington Square Arch. After completing the drawing, I began walking home over the Manhattan Bridge. Quite unplanned, I took a circuitous route on the Brooklyn side of the Bridge that led me up Myrtle Avenue and through Fort Greene Park.

I rolled my cart up a grassy hill to avoid the massive staircase that led to the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument. The staircase was being used for wind sprints by young women joggers. On top of the palisade, I weaved my way through parents and strollers to stare at the monument, which was indeed massive and in comparison to the Grand Army Plaza Arch, austere and inscrutable.

The monument is a massive beige obelisk topped with a simulation of a funerary urn that was once lit with an eternal frame. Remains of soldiers from a crypt at earlier monument were re-interred in crypts under the monument. These crypts have suffered continual vandalism in the decades that followed the monument’s construction in the late 1800s and early 1900s. A commemorative inscription installed at the base of the massive stair was removed from the site and placed into storage. The eternal flame, perched high enough that, symbolically, it would have been visible to the misbegotten American prisoners, was at some point extinguished. The bronze of the urn had faded to turquoise green in the years since it was cast.

The Historian’s point was well taken. The Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument is indeed massive. The removal of the inscription and the abandonment of the soldiers’ remains to the vagaries of time and neglect, however, led to memories of the prisoners’ suffering fading from collective memory. A plaque was finally affixed to the monument in 1960 in order to recuperate the monument’s original purpose. For this essay, I finally rolled my cart back to Fort Greene Park on an afternoon in Mid-October in 2014 to draw the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument. The day was extremely blustery and the paper I was drawing on almost blew out of my hands. A couple of young boys, playing pirates in a fetid pool behind me, watched me draw as they described their pirate exploits. The weed covered pool served as their ocean. Asian men milled around me picking up leaves and scraps of garbage. Skateboarders alternated between practicing tricks and hanging out at the base of the monument. One of the pirate boys interrupted his play to suggest that I draw two large concrete balls flanking the monument. I took his advice. The suggestion of the balls gives the picture much needed depth.

There is enormous irony in writing about things intentionally made invisible to accompany drawings of things I see. Yet in these encounters with the visible, I see the mockery of that which was forced or left to disappear.

I visited the Twin Towers to huddle with a few others in a small room on the ground level of Seven World Trade Center. We were listening to descriptions of the African Burial Ground and its mission. Upon leaving the meeting, I never imagined that the Twin Towers would be erased in a single morning a month or so later. 9/11 was one of the few moments in this City’s existence when erasure was imposed upon New Yorkers. Hurricane Sandy was a second millennial event thrusting an external will onto the city. New Yorkers, for better or worse, are habituated to mapping our own negotiation between the things we preserve and those that we bury. The thought of becoming habituated to external forces imposing these choices upon us by other people or nature is terrifying. Long after those trying days of the Battle of Long Island, United States’ role in the world has evolved to impose erasure upon others, not to be the subject of these choices made by others.

The modern urban landscape is a perpetual dance of creation and erasure. We constantly bury the past in order to build anew. The choices of preservation and elimination that we undertake may seem reasonable at the time. Public monuments, however, are concrete, durable additions to our collective physical landscapes. They endure for decades, centuries and occasionally millennium. Future individuals invariably perceive these artifacts through a vastly different lens than those who brought them into being. In the millennium, we may view the four bronze warriors at the summit of Battle Hill as inscrutable or perhaps noticing that the figures do not in any aspect resemble those who actually fought there, perverse. After encountering the African Burial Ground National Monument, we may also view burying the remains of the enslaved under tens of feet of fresh soil followed by poured concrete as mercenary.

A man who lived in the apartment above me became a police officer in the late 1990s. After 9/11, he was tasked with the unhappy duty of cataloging remains discovered in the fiery pit of Ground Zero. This work made him sullen. He went from being a generally cheerful person to having the spark of joy driven from him. He disappeared one day from our lives along with his wife and two children.

The preservation of the remains leading to the destruction of this man’s spirit and preservation of the remains from the African Burial site received the same reverent regard. No matter how small or fragile, they were painstakingly cataloged and maintained. Wikipedia refers to ‘Hogsheads’ as remains of prisoners from the British war ships carried up the Fort Greene palisade to be interred in the crypt below the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument. I can imagine buckets full of random phalanges, mandibles, and vertebrates mixed together in large baskets and poured into the crypt at the base of the monument. Sealed away until vandals broke into the crypt. Soldiers—British, German, and American—who fell along the high Palisades of Prospect Park during the Battle of Long Island are perhaps still buried where they fell under Frederick Law Olmsted’s magnificent ‘great lawn’ that serves as a dog run every morning before nine. Obviously radically different set of motivations informs these vastly different approaches to human remains.

These ideas first occurred to me after drawing Washington Square Park Arch in October 2014. During the four years of the “Anna Pierrepont Series,” I have returned repeatedly to draw two Washingtons forever frozen on adjacent piers and staring impassively up 5th avenue. On this afternoon, I sat further back in order to draw the monument in its entirety.

Erasure frustrates me as an artist. I briefly considered manipulating the digital reproduction of my drawing of the Washington Square Arch to ‘correct’ my rendering of the existing structure by including, from my imagination, an image of a historical event that took place in the shadow of the arch but that had not been preserved in a public monument.

Political violence, pestilence, public corruption, public displays of licentiousness, drunkenness, domestic violence, thuggery, murder, real estate speculation, inward and outward immigration, my own family’s early days in the United States, and of course slavery and terrorism all took place a stone’s throw from Washington Square Park. Abstract Expressionism arose in also in its midst, as did Minimalism and all the other 20th century artistic movements. Beat poetry, Bee-bop, and folk music were recited in nearby cafes. Unionism rose at Union Square Park as the Washington(s) gazed northward in that direction. The counter-culture emerged in the park behind them. My mind’s eye recalls the park as a backdrop to the film version of “Hair.” A woman belting out a plaintive song of reproach to her supposedly idealistic former lover as he wanders away in disgust.

I decided against altering my picture. My practice focuses on representation of the things encounter visually during my wanderings. I do not create drawings of things that are buried or were never created in the first instance. The “Anna Pierrepont Series” does not seek to correct choices made by others, but to illuminate and learn from them.

The intent of all of monuments I encounter and will encounter in the future is to tell of things that societies writ large, families or individuals, believed important enough for preservation. No matter where I go in seeking the remnants of the past that still remain, I stumble upon locales where past events have been wiped away or are barely acknowledged. The African Burial Memorial is a rare exception. On the weekend leading up to Halloween in Fall 2014, I drew the green mounds at the Burial Memorial. The memorial is on the site of one of the most militarized streets in Post 9/11 United States. The Ted Weiss building is the home of the Department of Homeland Security, behind it is a Court of International Trade. Due east is the Federal Court for the Southern District of New York and One Police Plaza. As I was drawing, I was passed by a couple of families dressed in Halloween costumes. Federal Park department officers standing in front of the Memorial chatted with the occasional person passing by or entering the monument. A man made note of the fact that he had never seen another person sketching the monument before he saw me doing so. The monument is so modest that artistic neglect is not a surprise.

The weekend before, I also made my first drawing at Ground Zero, as it emerges from its much delayed and painstaking reconstruction. Fences that have concealed the site for over a decade are finally being removed. Rising at the front of the site is Santiago Calatrava’s bird-like transportation center. 2014 has seen the building’s slow emergence. It possesses two enormous sets of radiating protrusions resembling bones, ironic in terms of this essay, projecting straight outward from a rib-like spine. I drew the center as a construction crane hovered above it. Unlike the aforementioned bones, the bones of the Calatrava monument are still attached to each other, resembling a prehistoric winged fossil frozen in pre-flight. I have not yet visited the 9/11 Memorial—a watery cascade that plunges into the footprint of the erased Towers. I have traveled on the World Trade Center Path train through the ruins of the footprints on many occasions until tunnel walls were constructed to block views of raw concrete and rust-covered steel girders. The first time I entered that station, I felt the weight of the disappeared legions pressing against my consciousness. This feeling has faded somewhat in time, but has never disappeared.

I can well imagine the emotions that New York’s descendants from slaves must have felt when the remains of perhaps some of their ancestors were uncovered from the site of their deliberate erasure. Groups of individuals came together to return the buried slaves to visibility. A museum at the site of Ground Zero attempts the same for the victims of that man-made catastrophe.

Human being in prior decades opted to erect monuments to the Civil War on sites of battles in the Revolutionary war. They also shoveled mounds of soil over the slave graves. We uncover ancient graves and create painstaking inventories of the bones that remain in those graves. We undertake the same process for the thousands of remains discovered at Ground Zero. What process is undertaken when inevitably the bone fragments of one of the men who may have been in the cave with Bin Laden or commanded by one of these individuals are inevitably discovered? In such moments, the impulse to preserve instantaneously switches to the impulse to erase. As with the past decisions specific to the Battle of Long Island or the African Burial Ground centuries ago, the impulse to downplay, soften and erase reemerges in a radically different context.

Those that turned the top of a palisade into a traffic island with an enormous arch dedicated to the Union army or who built the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument, did so because they felt exuberant pride in the first instance or diffident obligation in the second. As I have been discovering in the years of working on the “Anna Pierrepont Series,” monuments are not reasonable. They manifest as a result of complex and often contradictory and very human passions and convictions. The psychology, ambivalence, and often misguided worldviews revealed in their manifestation fascinates me, humanizing those with sufficient social and political to carve them into my immediate surroundings. As in Ground Zero and the African Burial Memorial, choices of a similar nature and under radically different circumstances are being made by my contemporaries. I am equally haunted by those whom this process reduces to traces. The “Anna Pierepont Series” places a mirror up to these contradictory and painfully mediated choices. The other side of the mirror’s reflects me forcing the “Anna Pierrepont Series” into being. The fact that these efforts are visible to my eye, pencils, chalks, and oil sticks, along with all their contradictions, perversity, and shortcomings, I find profoundly moving. The mirror lacks a third face, and marks remain unmade for the erased, moving me even more.

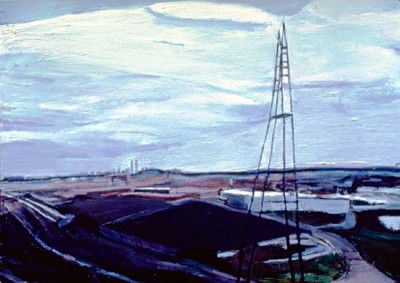

This acrylic painting on canvas is a testament to the once visible and now erased, the Twin Towers as seen from New Jersey in 1995.

Howard Skrill is an artist, researcher, and college professor. He is the principal studio arts teacher at St. Francis College in Brooklyn Heights, N.Y., and also teaches art history lecture at St. Francis and drawing and sculpture at Essex County College in Newark, N.J.

Howard Skrill is an artist, researcher, and college professor. He is the principal studio arts teacher at St. Francis College in Brooklyn Heights, N.Y., and also teaches art history lecture at St. Francis and drawing and sculpture at Essex County College in Newark, N.J.

0 comments on “Nonfiction: Howard Skrill”