The Long Light of Prose:

An Interview with Lee Martin

by Karin C. Davidson

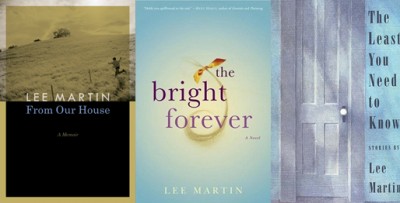

Lee Martin understands the language of landscape: the way light falls over a field with respect to the season, the differing sounds of neighborhoods in a small Midwestern town, the cold snap called blackberry winter, the idea of origins and belonging that all have to do with place. His short stories, novels, essays, and memoirs—“The Least You Need to Know” (Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction winner), “The Bright Forever” (Pulitzer Prize finalist), “Break the Skin,” “From Our House,” “Such a Life,” and many others—transport one to the places of childhood, memory, understanding, misunderstanding, anger, and compassion with the clarity and patience of a man seriously devoted to words. Portraits of farmland and family, of seasons and time passing are revealed in the details: wheat kernels, killing frosts, marigolds and zinnias, the worn arms of a rocking chair, the trace of a smile. These details—perfectly placed, lingered over, returned to—ground us, allow us entry into and passage throughout the story.

Lee Martin understands the language of landscape: the way light falls over a field with respect to the season, the differing sounds of neighborhoods in a small Midwestern town, the cold snap called blackberry winter, the idea of origins and belonging that all have to do with place. His short stories, novels, essays, and memoirs—“The Least You Need to Know” (Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction winner), “The Bright Forever” (Pulitzer Prize finalist), “Break the Skin,” “From Our House,” “Such a Life,” and many others—transport one to the places of childhood, memory, understanding, misunderstanding, anger, and compassion with the clarity and patience of a man seriously devoted to words. Portraits of farmland and family, of seasons and time passing are revealed in the details: wheat kernels, killing frosts, marigolds and zinnias, the worn arms of a rocking chair, the trace of a smile. These details—perfectly placed, lingered over, returned to—ground us, allow us entry into and passage throughout the story.

Just after dawn, the skies opened up, and rain fell. It came in silver sheets, falling straight down. It fell over the cornfields and the wheat fields and the soybean plants in their straight green rows. It fell over the woodlands, soaking down through the canopies of the hickories and the oaks and the sweet gums. It drummed the tin roofs of barns and grain bins. It flattened pastures of timothy and the turkey foot grass on the prairies. It pocked the White River and the lake at Shakamak. It muddied the shale roads and left them slick and black.

–Lee Martin

KARIN C. DAVIDSON: Lee, in your writing there are various kinds of landscapes. The landscape of countryside, of community and family—that which includes farmland, small towns, main streets, schools and dime stores, front porches and backyard gardens, bright kitchens, bedrooms alive with stereos spinning ’70s rock, hallways lined with family pictures. And then there is the more interior landscape, one that reveals the habits and thoughts, the happiness and secrets, the dreams and sadness of your characters.

Would you tell us how you approach the details of place, whether temporal or topographical, within the recesses of a barn or a character’s mind?

LEE MARTIN: Our lives and the stories they tell are in the things around us—in the literal geographic landscape that we occupy and in the ones that we manufacture by the things we choose to buy, choose to keep, choose to discard. I think of myself as part anthropologist, part archaeologist, part geographer as I begin to sketch in a landscape for my characters. I sort through the objects, take note of the terrain. From there, I work my way inside the characters, finding out more about them as I go. “First, notice everything,” the poet Miller Williams says in his poem “Let Me Tell You,” a poem about how to write a poem, but it’s really about how to write anything. “Miss nothing, memorize it,” Williams says. For me, this is where my work as a writer often begins. I catalog what’s there to be seen, heard, smelled, tasted, felt. Gradually, characters emerge from all those details. They move through the world I’ve created, and as they do, they start to reveal themselves.

DAVIDSON: There is a pastoral element to your novels, stories, and memoirs that beautifully opposes the complex lives of those portrayed. In your novel “The Bright Forever,” Mr. Dees reveals layers and layers of himself, each one more surprising than the one laid before. In the story “Light Opera,” elegant afternoons of opera are contrasted to evenings spent in a funeral parlor’s embalming room. The chapters of the memoir “From Our House” deliver an honest and compassionate tale of a boyhood like no other.

How does the natural world play into the design of those portrayed?

MARTIN: As the son of a farmer, I grew up very aware of the way the seasons and changes in weather affected our livelihood. This connection between the individual and the natural world became elemental to me, something that couldn’t be broken. I learned as I aged that I was who I was in part because of where I was. I know there are some people who come from more dramatic landscapes and who think the Midwest has no natural beauty. Perhaps we have to look a bit more closely to find it, say in the subtle nuances of color in a field of corn stubble in winter, but that’s a good thing. It means we see more fully. We pay attention in the same way that we do when we start to think about what it must be like to live inside this or that person’s skin. My characters, then, can never be separated from their landscapes. They define themselves in the way they act within, or respond to, those natural worlds. A man spends his days driving a tractor up and down a field, and he feels every bump and cut of that ground until he takes it in and his living takes on its rhythm. A man like Mr. Dees watches the purple martins swoop and dart above a flat land that stretches out to the horizon, and he starts to think about what holds him in place and what threatens to leave him untethered.

DAVIDSON: John Carr Walker (one of your former students at the Vermont College of Fine Arts Postgraduate Workshop and also interviewed in this issue) writes about relationships, especially sons and fathers, usually from the son’s viewpoint. I’ve noticed your stories and novels share this focus. “The End of Sorry,” in your story collection “The Least You Need to Know,” is such a story, in which the son sees his father ostracized by townspeople for taking on work in a slaughterhouse despite the ongoing strike where union workers are demanding a fair wage. The son is eventually cut off himself, and relentless, the father digs himself in deeper and deeper.

What leads you to these kinds of stories, these kinds of pairings, so tied with the tension of anger and distrust, as well as respect, understanding, and hope?

MARTIN: I’ve always been interested in the fine line between cruelty and compassion and how people negotiate it. After the farming accident that cost my father both of his hands, he became an angry man. My mother was a woman of faith. She was kind, patient, loving, and compassionate. I grew up caught between both of their influences, and for that reason, I suppose I’m drawn toward stories told by young boys who find themselves being a part of their parents’ stories. I’m interested in what happens when the adult world of ambition, deceit, and misinformed love runs up against the child’s world of the earnest and genuine heart. Something gets formed in the friction between the two. I like working with stories that capture that moment when before turns into after.

So often that summer, my father asked me to do something beyond my limits: to loosen a rusted nut on a piece of machinery, to lift a cultivator and pin it with cotter keys to the tractor, to set the steel traps. “I can’t,” I often told him, and he replied, “Can’t never did nothing. Try it again.”

–Lee Martin

DAVIDSON: There are expressions from generations past that you include in your writing, holding each up to the light, catching its sparkle and shine in the phrasing and context, letting your readers fall directly into the moment of that time gone by.

What are some of your favorite expressions from the past and present?

MARTIN: My father was a great one for colorful expressions. I still remember him cautioning me when I was misbehaving: “Mr., you’re breeding a scab on your ass.” Or he’d say someone was “as full of shit as a Christmas turkey.” He also liked to say, “If ifs and buts were candies and nuts, we’d all have a merry Christmas.” When I would ask for something and he’d refuse, I’d say, “But I want it.” He’d answer, “People in hell wanting ice water, too.” I imagine that most of these sayings had been passed down to him from our ancestors who came to Illinois from Kentucky. I’m grateful for the sound of them and others, and every time I use one in a piece of writing, I feel like I’m for a brief moment in touch with all the ancestors I never had the chance to know.

DAVIDSON: Writers are often told to write from what they know, and then there is the moment of curiosity in which a writer wants to write beyond what is known. As someone who writes from both perspectives, you cross from memoir to fiction with grace and ease, the touchstones of language and landscape always present.

Tell us how you prepare and then compose when writing from the viewpoint of a 9-year-old girl, a murderer, a Texas tattoo artist.

MARTIN: I’ve never been one to shy away from writing from the perspectives of people very unlike me. I believe it’s my job as a writer to practice the art of empathy, to be able to dramatize what it is to be that 9-year-old girl, or that murderer, or that Texas tattoo artist. As I move through the world, I listen. I take in the rhythms of people’s lives. I hear their vernacular. I get a feel for what pleases them, what oppresses them, what they long for, and what they fear. Then, as I start to build a character, I find what I have in common with him or her—yes, even that murderer. I find what we all hold in common, and I use that as my controlling principle. The Texas tattoo artist, for example, just wants to feel love and to give love in return. I may not be a Latina, but I know what it is to want those same things. That murderer was once a boy isolated because of difference. I know what that feels like, too. And that 9-year-old girl? Well, I always say I have a little boy who after 59 years still lives inside me. He’s the part of me who collects windup toys and loves corny jokes. He wants to be silly and to feel unadulterated joy. And I’ve listened to women talk about their childhoods. I’ve listened to their stories. Somewhere along the line, what I know from my inside meets what I’ve gathered from the outside, and these characters come to life.

On the night it happened—July 5—the sun didn’t set until 8:33. I went back later and checked the weather cartoon on the Evening Register’s front page: a smiling face on a fiercely bright sun. I checked because it was the heart of summer, and I couldn’t stop thinking about that long light and all the people who were out in it; I’d seen them sitting on porches, drinking Pepsis and listening to WTHO’s Top Fifty Countdown on transistor radios.

–Lee Martin

DAVIDSON: I love that liner notes are listed at the back of “The Bright Forever.” They include songs from the era in which the story takes place: Daddy Dewdrop’s “Chick-a-Boom,” Charley Pride’s “Kiss an Angel Good Morning,” Sammy Davis, Jr.’s “The Candy Man,” and Carole King’s “It’s Too Late.” And then there is the music that inspired the writing: from Joni Mitchell’s “Chelsea Morning” and Neko Case’s “Tightly” to songs by Bob Dylan, Bonnie Raitt, Lucinda Williams, and of course, the hymn from which the novel takes its name, “The Bright Forever.”

As you work on newer projects, whether fiction or nonfiction, does music continue to add another level of inspiration to your writing?

MARTIN: I’m always listening to music and hearing in it something that speaks to me and that demands a response. I can’t sing. I don’t play a musical instrument. So I answer with language.

Karin C. Davidson, Interviews Editor

0 comments on “Interviews: Lee Martin”