Fame and Fiction: A Night

with Frank Bidart and James Franco

Jaime Groetsema

James Franco and Frank Bidart, Off the Shelf

February 19th, 2014

Thorne Auditorium, Chicago

I. Prelude

I. Prelude

I was riding the city bus recently. Not an uncommon occurrence.

I was on my way to a boot store.

I wanted to buy a pair of green goat-skinned cowboy boots.

(Not all of the money in my possession was my own.)

I was reading “As I Lay Dying.”

The bus smelled of urine. What’s new.

A man looked familiar.

I thought I may have sold him books.

He leaned over.

He said what I was reading was his favorite book.

His pleasure made me nervous.

I smiled and said, “Faulkner.”

“Faulkner is great.”

He had been grinning and continued to.

I hid behind Cash and Darl.

I looked and the man still seemed to feel pleased.

I thought about Faulkner drinking.

About Faulkner being old.

About Faulkner in the commercial produced by the Ford Foundation.

About Faulkner winning awards.

About the Pen Faulkner award.

About reading Faulkner in Berlin.

There, I read Faulkner in bed.

Lying, I rehearsed Addie’s lines.

I thought of myself as old.

I thought of winning awards.

I thought of being in love.

I was pleased.

I smiled.

I was on the bus staring at the page.

The lettering on the page became crisp.

I could read it.

The words seemed real.

The man I thought I recognized was getting up.

Was whispering in my ear.

Was whispering and grinning: enjoy the book.

I couldn’t read it anymore.

The book was no longer mine.

I imagined every line whispered.

Faulkner whispering the lines to himself.

Faulkner pressing the keys and whispering.

Someone coming later to take the typewriter ribbon.

And selling it.

And selling it again.

And auctioning it.

And it going somewhere.

To someone else.

To a box. In a temperature-controlled room.

Where later, I imagined, that person I loved would take it out of the box and measure the tape and make notes, personal notes about the ribbons and about what they said, constructing a whole narrative himself of that which was supposedly said.

And that being “As I Lay Dying.”

And that not being whispered.

And me trying to finish the novel.

And finally finishing the novel on the bus.

II. Epilogue

II. Epilogue

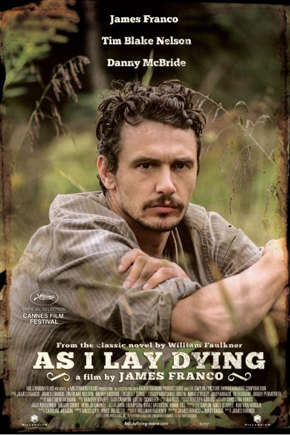

Finishing it, sadly, after watching James Franco’s film adaptation of “As I Lay Dying,” and sadly, returning to those actors cast as Addie and Cash and Darl and Tull and them being all wrong, but stuck in my head as I read along and finished the novel. Addie too soft and too loud, too much a human. In the film, she was much closer to life than to death; and Darl never in a daze, never an artist. He was too crazy to be more than that. The punch line coarse and distracted and separate from the rest of the story because it wasn’t what it had been to me before it was someone else’s.

III. Afterward

James Franco took the stage at the Thorne Auditorium in Chicago and the audience hooted and clapped as if there were no other artists on the stage. Some people laughed at James Franco because he made jokes that were supposed to be redeeming but made him look stupid instead. Some people who had pre-ordered his new book “Directing Herbert White: Poems” (Graywolf Press, 2014) diligently read along as he read his poems aloud: “There is a painting of a blonde sailor / dressed in blue and red and white / a stoic version of myself.” James Franco spent much of the discussion being a boring person, listing the details of his life, but those details eventually added up to what I read as a kind of recognition of himself as a cultural producer. He said that he did what he did—his activities, were done so, because of the mere impetus of—were more or less a product of he being on the inside, having a lot of money and opportunity and connection. This means James Franco is an active cultural producer, which I think many people would not disagree with. That doesn’t mean that what James Franco is producing is good. Good is something different. Good resides in a world that is not solely built with the language: fame and fortune, opportunity and connection.

I watched the ass of James Franco’s personal assistant, wrapped in a tight dress made of yarn, outlined, I imagined, by a secret intent to express a powerful sexuality, prowess, inhabited by what could perhaps be a thong, but never a thong strong enough to encompass the various speeds of that moving ass that shifted and rocked along a tight waist, at a speed unprecedented in the history of the event thus far, for the mere fulfillment of bringing a plastic cup filled with water and ice chips from point A to point B and being satisfied by existence and being and by being close to someone who does things the way that James Franco does things.

I took some images with my cell phone. I like best the one where James Franco is obscured by the hair of the woman sitting in front of me. The strands of her hair drawn out from her scalp move over him and divulge him.

I took some images with my cell phone. I like best the one where James Franco is obscured by the hair of the woman sitting in front of me. The strands of her hair drawn out from her scalp move over him and divulge him.

Frank Bidart is sitting to the left of James Franco in the photographs. He is a poet and has been invited to the event because he has written a poem that influenced James Franco. The poem titled “Herbert White” is about a man who murders young women and has sex with their corpses. The poem seeks to showcase that man’s personal struggles with an affliction that he must keep secret from his family. Frank Bidart read his poem aloud with vigor and ease. He published this poem in 1973 and it is only the third time he had read it in front of an audience.

Frank Bidart is sitting to the left of James Franco in the photographs. He is a poet and has been invited to the event because he has written a poem that influenced James Franco. The poem titled “Herbert White” is about a man who murders young women and has sex with their corpses. The poem seeks to showcase that man’s personal struggles with an affliction that he must keep secret from his family. Frank Bidart read his poem aloud with vigor and ease. He published this poem in 1973 and it is only the third time he had read it in front of an audience.

James Franco wrote and produced an adaptation of Frank Bidart’s poem for his film class. The short film was shot in HD and screened at the event. James Franco uses a crane as a metaphor. Michael Shannon plays the lead. The short film reminded me of James Franco’s adaptation of “As I Lay Dying.”

I think of Faulkner, walking in archival film with stiff thin legs and knees that make a point between two segments of line. I think about Faulkner writing “As I Lay Dying” when he was broke. Faulker writing chapters in between shoveling coal and dropping it into a furnace after midnight—graveyard shift.

He uses a walking stick across a gravel lane, bits of stone beat under his feet, changing the slope of silt and layers of debris; working a new form in path. The grain of the film exposes great explosions of light and dark, shifting sand bubbling around his movements. He speaks through coal and ash and fire, and through sawdust, trying desperately to mask the stench of death.

The duration of the footage of Faulkner walking is 20 minutes long, but I think of it shorter, transferable: an animated .gif looped and made into a meme. The compressed form makes digital bits, small squares that harden his figure and erase him. This fading image of Faulkner is only a whisper: William Faulkner come and gone.

After watching James Franco’s short film, he compares the secret affliction of the murdering necrophiliac with that “secret affliction” that a homosexual male carries: his sexuality.

I balk and scream inside.

What of Faulkner is left to us?

Faulkner bending at the knees.

His body crushing into a fetal position.

Spinning out of time and fading away.

Bidart sitting with his swaging head.

He scrunches into his eternal scissor legs.

A compressed accordion never to make sound.

Next, James Franco and Frank Bidart read aloud one piece of each other’s work. Someone at the event referred to this last part of the event as a “special treat,” though I can’t recall who said it exactly or when.

Then, as a final act, James Franco read his poem that was about making a film based on a poem. The audience clapped. The event organizer, loud, despite her frame, asked that those that desired James Franco’s autograph to please form a straight line. The gentleman sitting next to me started up quickly and said in my direction, referring to the event organizer, “I hate that woman. Let’s get out of here.”

Dazed by the whole evening, I thought for a moment that maybe the man sitting next to me had confused James Franco for a woman and that’s who he was directing his disdain towards. Or, I thought perhaps that the man was upset by the fact that Frank Bidart had been largely obscured though out the event despite the limp reach of the woman’s hair in front of me.

James Franco talked a lot. He did mention that he liked encountering adolescence as a thematic concept, but mostly filled the space with facts about himself and efficient lists of things he had done.

IV. A Note on the Text

In a later chapter of “A Room of One’s Own,” Virgina Woolf considers the prose of a contemporary popular male writer, Mr. A. She begins reading one of his novels in an attempt to analyze the possibilities of the writing containing masculine characteristics, but due to extreme use of the perspective “I,” she finds she is unable to continue and asks herself, “But why was I bored? Partly because of the dominance of the letter ‘I’ and the aridity, which, like the giant beech tree, it casts within its shade. Nothing will grow there. And partly for some more obscure reason. There seemed to be some obstacle, some impediment of Mr. A’s mind which blocked the fountain of creative energy and shored it within narrow limits.”1

James Franco, like Mr. A, spent a negligible amount of time talking about anything that could even slightly be considered an idea or belief. There was no extended conversation that attempted to define what it meant to James Franco when he simply said, “I thought it was great.” There was much of that word “I,” however, to fill up the space.

The successes of the event, if there are any, seemed to have resided in the fact that someone like James Franco exists and what makes his individual existence a special or curious one is that he said something and then he did something. Both the saying and the doing, in this case, come from as he said, his social and financial opportunities.

The persistence of this kind of cultural production leaves interested parties with nothing much to talk about and puts everyone listening in a situation which it seems appropriate to say of James Franco: I hate that woman.

1Woolf, Virginia, “A Room of One’s Own.” Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich, Inc., New York: 1929.

Jaime Groetsema, Reviews Editor

0 comments on “Reviews: As I Lay Dying”