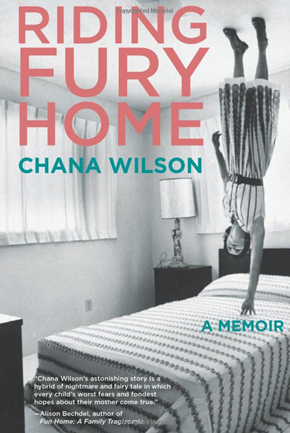

Riding Fury Home: A Memoir

Chana Wilson

During the day, Mom was relatively able—sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on what, I never knew. Her daytime medications, the sedatives and tranquilizers, didn’t knock her down into staggering oblivion like the nightly sleeping pills. She managed to keep us fed. After school, I came home to my mother’s kiss, her welcome of “Hi, darling,” and a snack—apple slices with Cracker Barrel cheddar cheese, Pepperidge Farm goldfish and a glass of milk, or sour cream and blueberries sprinkled with sugar. Then, there was my after-school routine of doing homework and a half-hour of piano practice, after which I would run over to Barbie’s—two houses away— and play until dinner.

During the day, Mom was relatively able—sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on what, I never knew. Her daytime medications, the sedatives and tranquilizers, didn’t knock her down into staggering oblivion like the nightly sleeping pills. She managed to keep us fed. After school, I came home to my mother’s kiss, her welcome of “Hi, darling,” and a snack—apple slices with Cracker Barrel cheddar cheese, Pepperidge Farm goldfish and a glass of milk, or sour cream and blueberries sprinkled with sugar. Then, there was my after-school routine of doing homework and a half-hour of piano practice, after which I would run over to Barbie’s—two houses away— and play until dinner.

When we were alone, the protectiveness I felt toward my mother around others ebbed away. The anger that I tried to bury would erupt, but only at insignificant matters. I hated the noises Mom made when she ate. Her teeth had rotted while she was in the mental hospital, and the dentist there had extracted all her upper and some lower teeth. She had come home, at thirty-eight, with a full upper set of dentures and a partial bridge. The false teeth clicked as she chewed. Sometimes, I’d yell, “What are you, a pig!?” When she simply shrugged, or her eyes got moist with tears, I felt terribly guilty. But I couldn’t seem to stop my nasty remarks.

Sometimes on the weekends, we would go to the movies in Princeton. Once, Mom and I were breezing along River Road, a windy two-lane. It was a crisp fall afternoon and we were going to a matinee. My mother was in a reasonably good mood, and her driving phobia hadn’t kicked in, so I relaxed in the passenger seat of our Hudson and watched the orange and gold foliage pass by, trailing my hand out the side of the car, feeling the rush of air. As always, my mother was smoking a cigarette. When she was down to the filter, she stabbed it in the ashtray with her right hand, her left hand on the wheel; then, flinging her right arm across her chest, she flicked the butt out the window. This interrupted my reverie because I had to dig another Tareyton out of her purse while she punched in the cigarette lighter.

Princeton’s only movie theater stood in the center of the small, neat upper-class town with its Gothic university buildings. It was almost as if a cloak of hush had been draped over the town, an air of restraint epitomized in the muted plaids and dull tans of expensive preppie outfits. It made me feel especially conscious to act right and not stick out.

We parked in the lot behind the theater, stopped in the lobby for refreshments. When the theater lights dimmed, I was swept into the cinema world—the aroma of salty butter, the crunch of popcorn, the sweetness of Coca-Cola, the sound of Raisinets running along their cardboard container into my hand.

After a matinee, there was always the shock to find it still daylight. But that was nothing compared to what Mom and I found when we got to our car. Firemen in their black helmets and yellow raincoats had pulled the back seat onto the parking lot asphalt, and they were just finishing spraying it with fire extinguishers. Stinking black smoke wafted up. The seat was incinerated, and I could see its metal springs poking through the charred padding. Our car was a spectacle, and a cluster of people was gawking in silence.

One of the firemen came over to my mother, as we stood staring at the car seat. “Ma’am, this your car?”

Mom nodded and smiled weakly.

“Did you have a lit cigarette that you didn’t put out properly?”

Shame flamed in me, prickling my skin.

“I thought I had,” she answered. “I stubbed it out and threw it out the window.”

“Well, Ma’am, be more careful next time.” He stated the obvious, like my mother was some kind of simpleton. I wanted to escape, disappear. Here we were again, Mom and me, standing out, looking weird. Is it both of us, or just my mother?

As the spectators began to drift away, the firemen loaded the charred frame of the seat into its place in the back of our car. The one who had talked to Mom raised his hand to his brim, and wiggled his hat at Mom before they left.

“Let’s get the hell out of here,” Mom said.

Excerpt from “Riding Fury Home: A Memoir” by Chana Wilson. Seal Press, Publisher.

©Chana Wilson. All rights reserved.

Chana Wilson is a psychotherapist, former radio producer, and award-winning author. Her essays and stories have appeared in several print journals including The Sun and Sinister Wisdom. She also blogs for the Huffington Post.

0 comments on “Nonfiction: Chana Wilson”