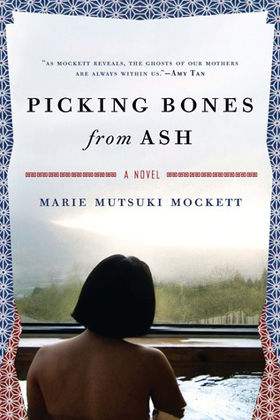

‘Picking Bones from Ash’

Donelle Dreese

Marie Mutsuki Mockett, “Picking Bones from Ash”

Marie Mutsuki Mockett, “Picking Bones from Ash”

Graywolf Press

2011, 320 pages, paperback, $14

Marie Mutsuki Mockett’s “Picking Bones from Ash” is a rich and unraveling novel that spans three generations of women and travels the globe from Japan to France to San Francisco. The story challenges readers to reconsider their perceptions of Japan and Japanese women in Asian American literature, to accept both the beauty and chaos of the nonhuman natural world, and to ponder how far the painful reverberations of sibling rivalry can reach.

Some context: When Mockett set out to write this compelling work, she aimed to offer readers a few narrative surprises while also presenting Japan as more than simply a land of “temples and tea.” She had hoped to offset the dominant Buddhist images that define perceptions of Japan in Western countries, and portray a culture that is diverse and complex. She took the same approach when developing the female characters in the novel. “They would be modeled on the Japanese women I knew,” she states, “and not the flimsy, suffering-but-beautiful stock characters I’d run into in so many historical novels written by Western authors.” Indeed, the three central characters in the novel—Satomi, her mother Akiko, and Satomi’s daughter Rumi—are all brimming with intellect, strength, and astonishing talents. Satomi is a brilliant pianist and Rumi is a sharp and intuitive Asian art dealer who can hear the histories of art pieces just by looking at them.

The novel intrigues readers from the outset as Satomi depicts her childhood in a small Japanese mountain town in 1954. She presents the kind of childhood we might expect—adventurous and spirited—as she describes roaming the forest near her home searching for bamboo despite the warnings that the forests were filled with demons and monsters. But the woods clearly served as a place of beauty, refuge, and curiosity for Satomi. She narrates,

Although I wasn’t immune to the potential terrors of the woods, I thought of nature as being my friend and believed that it would always protect me. I had names for the sparrows who ate osenbei crumbs from my window. In early spring, when the yabutsubaki while camellias bloomed, I made necklaces from their flowers and little whistles with their dark brown seeds. When the other children chased the home from school, I could hide in the tall weeds while they ran past. (7)

In the forest, her imagination would allow her to be anything, including a female ninja stalking the difficult terrain, seeking the bamboo grove at the heart of the forest to save the Moon Princess. After an elderly woman gives her bamboo shoots, Satomi takes the shoots home to her mother who prepares them for dinner. At this point in the novel, readers understand that Satomi’s mother has plans for her daughter that will set her apart from the other children in the village.

For fear that she will damage her fingers, Satomi is forbidden from taking bamboo shoots because she must protect her hands in order to compete in a piano competition. Satomi is told by her mother that she is “unique” and different from everyone else, which isolates her from her friends and siblings in ways that impact the rest of her life. Indeed, the jealousy this attention provokes in her stepsisters unfolds a series of events that impact nearly all of the characters in the novel on some level. Although by the end of the novel she is surrounded by friends, Satomi lives out this destiny of isolation well into old age when she lives in a remote area of Japan with a career, not as a pianist, but as a successful writer.

In a brief essay at the end of the novel, Mockett describes the influence of Japanese stories that inform her work. In many of these stories, “nature was often a powerful character, adding a quality of chaos to the universe.” In “Picking Bones from Ash,” nature is portrayed as both alluring and overwhelming. The bamboo forest in the beginning of the novel floods Satomi with cold as she describes the forest as suddenly “invaded by fog.” This chill weighs heavily on Satomi as she feels “icy pressure” on her neck and a cold hand grip her wrist. A presence from the woods overtakes her body and she felt its “clammy tendrils intertwine” with her own fingers (8). At the end of the novel, when Rumi is traveling to see her mother, Rumi must travel to an inactive volcano that is known as “the gateway to hell, the entrance to the underworld, the place where little children’s souls were trapped, unable to cross to the other side because they hadn’t accumulated enough karma to be completely worthy of rebirth” (229). Rumi is instructed to walk the mountain foothills alone where she ultimately passes out from the smell of sulfur from misting mineral pools. Mockett does not idealize nature in her novel. She presents different forms of wilderness, all of which are inspiring, stunningly beautiful, and perhaps somewhat magical, but they are also places that provoke fear and are dangerous to human sensibilities.

While the novel’s conclusion takes place in a Buddhist temple, a place stereotypically associated with Japan, there is a secret hiding within the recesses of one of the Buddha statues that reminds us of the long-lasting impacts of unresolved familial conflicts. This theme reaches its climax in the novel when Satomi’s friend Masayoshi states: “When parents and children can accept each other—no matter what that means—their relationships with everyone else will change” (272). The implication of this passage is that when we can heal our relationships with our family members, we can heal our relationships with others, an idea that informs the novel’s many dramatic conflicts. Does Satomi forgive her stepsisters for cutting her out of her mother’s will and taking all of her mother’s belongings? Does Rumi forgive Satomi, her own mother, for abandoning her in California for so long that Rumi thought she was dead? Is Satomi forgiven for stealing her mother’s bones?

The great success of “Picking Bones from Ash” is threefold. First, the writing is descriptive in such a way that is poetic and almost dreamlike. Second, the novel is beautifully narrated by the alternating perspectives of Satomi and her daughter Rumi, and through these voices, readers bear witness to generations of characters who are struggling with loss and driven by the ghosts that haunt them. And third, the novel does not glamorize the gift of artistic talent, but in fact suggests that such gifts bring forth as much sorrow and isolation as they do opportunity and accolades. As “Picking Bones from Ash” closes, there are no easy answers to the conflicts experienced by the characters, which makes the end of the novel no less powerful. Though what is left is a small community who has suffered heartbreak and confusion, there is hope in the fact that they are closer to the truth about the past and moving toward psychological freedom.

0 comments on “Review: Marie Mutsuki Mockett”