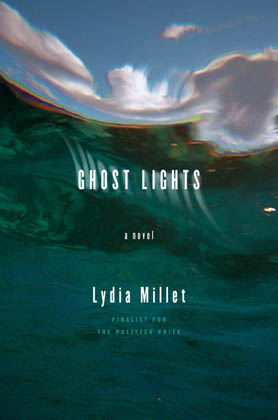

‘Ghost Lights’

Leslie Wolcott

Lydia Millet, “Ghost Lights: A novel”

W. W. Norton & Company

2011, 256 pages, hardcover, $16.47

A friend of mine recently spoke of escaping to “paradise” after a particularly hectic wedding. It bothered me, and after reading PEN-USA award winner Lydia Millet’s “Ghost Lights,” I think I can tell you why.

A friend of mine recently spoke of escaping to “paradise” after a particularly hectic wedding. It bothered me, and after reading PEN-USA award winner Lydia Millet’s “Ghost Lights,” I think I can tell you why.

In the book, as in in her other novels—“Omnivores,” “Everyone’s Pretty,” and “My Happy Life”—a fairly unlikely plot unfolds. The book opens as Hal and Susan, whom we met in her prior novel “How the Dead Dream,” are picking up her missing boss’s abandoned three-legged dog from a vet’s office.

Susan’s boss, T., has gotten tired of running his successful business in the U.S., and without telling anyone, has run away to Belize, leaving business, dog, and employees in limbo. While much of the plot unfolds in the search for the boss, this reader doesn’t really believe that he is dead. Because Hal has discovered that his wife has been cheating on him with the paralegal at her office, he, too, gets the idea that if only he could escape to Belize, he could play hero by finding Susan’s boss and somehow salvage his failing marriage. His real goal, though, is to escape the daily reminders of her infidelity as well as his discovery that his paraplegic daughter is happily employed as a phone-sex operator. Instead of confronting difficult aspects of his relationships, Hal hits the road.

Despite the unlikely plot turns and sometimes overbearing politics, this novel is ultimately about occupation. His wife’s paramour, the sexy paralegal, occupies Hal’s space as the romantic lead in his own marriage; various and sundry men occupy his daughter’s love life; and Hal himself occupies the wife of a German traveler, who is too busy occupying Belize’s military in partnership with U.S. forces to notice. Susan’s boss, T., it turns out, is occupying a now-defunct hotel island, using it to rebirth himself as a free spirited, money-shunning, long-haired hippie, and who, it turns out, is still wanted by the Belize authorities. By the end of the novel, he winds up occupying a local jail cell.

There is plenty of space in the novel devoted to revealing Americans’ blind spots when it comes to re-inscribing visions of paradise or poverty—sometimes simultaneously—over already occupied lands. In discussing her worries about T., and the search for him in Belize, Susan says, “I mean first of all it’s a small village in Central America. They’re poor. And they just got hit by a tornado.” Never mind that the small coastal country had just been hit by a hurricane, not a tornado—the country and the process of how things operate in it are “a big blank” to his wife. Hal, too, sees it as too distant to allow for change, freedom, and heroics, thinking to himself as he decides to travel: “It was settled. He would fly away from all of it and that would leave the field wide open.”

Upon his arrival in Belize, Hal does not meet people native to that land. Instead, he meets a German family: husband, wife, and two tow-headed boys, who are there for an unknown reason but take an unusual interest in Hal’s search. Ostensibly there to solve other people’s problems, conveniently the German husband combines Hal’s search with his own interest in putting his own hand (and that of his native Germany, as well as the United States) in the operations of the local military.

What’s the moral of the story behind all these occupations? Despite Millet’s attempt to tell the reader, word for word, what to think (with way too many suggestions of a Christ-like sacrifice), the real moral comes at the end with the death of the narrator. You can’t occupy a place without consequences, and he pays the ultimate price for his occupation. Street thugs take what they want from him (which, in fact, isn’t much), and leave him to die. While he bleeds, though, he sees his family, his coworkers, and his relationships with a new clarity, perhaps brought forth by his reduction to just another unidentifiable body lying on the street of an unidentifiable town in Belize. Hal abandons the sarcastic and critical commentary that has filtered the world for him until now, and he is left with a different understanding of his relationships. The not-so-subtle slow bleed out as Hal lies on the street allows the reader to absorb the idea that there is no escape in paradise. That, in fact, there is no paradise.

Leslie Wolcott, Staff Blogger

0 comments on “Review: Wolcott”