A Little Girl in a Big, Big Universe

Justin T. Noetzel

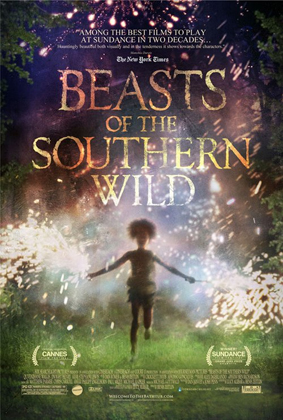

Benh Zeitlin, “Beasts of the Southern Wild”

Fox Searchlight Pictures

2012, 93 minutes

In 2008, writer and director Benh Zeitlin crafted “Glory at Sea,” a story of survival and rebuilding in the aftermath of what we can infer was Hurricane Katrina. The short film won multiple festival awards and now exists as a kind of prelude to “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” an imaginative and visually stunning feature film that chronicles the ramshackle tree houses, secondhand trailers, and oft-flooded landscape of a tiny Louisiana Delta community called the Bathtub. On personal and universal levels both of these films depict the unstoppable and inescapable movement from chaos and imbalance to order. The central character of “Beasts of the Southern Wild” is a young girl named Hushpuppy. Played with fantastic power and emotion by newcomer and Delta native Quvenzhané Wallis, Hushpuppy must learn that sickness often leads to death, ice eventually melts, and water inevitably rises and falls to its natural level.

In 2008, writer and director Benh Zeitlin crafted “Glory at Sea,” a story of survival and rebuilding in the aftermath of what we can infer was Hurricane Katrina. The short film won multiple festival awards and now exists as a kind of prelude to “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” an imaginative and visually stunning feature film that chronicles the ramshackle tree houses, secondhand trailers, and oft-flooded landscape of a tiny Louisiana Delta community called the Bathtub. On personal and universal levels both of these films depict the unstoppable and inescapable movement from chaos and imbalance to order. The central character of “Beasts of the Southern Wild” is a young girl named Hushpuppy. Played with fantastic power and emotion by newcomer and Delta native Quvenzhané Wallis, Hushpuppy must learn that sickness often leads to death, ice eventually melts, and water inevitably rises and falls to its natural level.

The rusty vehicles, driftwood dwellings, and general detritus of Hushpuppy’s coastal existence populate the Bathtub like flotsam and jetsam come to life. Hushpuppy’s narration begins the film by contrasting “the dry world,” with its claustrophobic “things stuck in plastic wrappers, babies stuck in cradles, and food stuck in supermarkets,” with her wet and messy world that is also brimming with freedom and ecstasy. When Hushpuppy and her ailing father Wink go fishing in the Gulf, they see a huge factory in the distance spewing smoke into the air. In this moment of immense intimacy on the open water, Wink tells her that they live in “the prettiest place on earth.” The Bathtub also has more holidays than anywhere else on the planet, and an average celebration features children frolicking, adults playing music and drinking, and everyone parading down the town’s one dusty road and setting off fireworks throughout the night.

While Zeitlin emphasizes the natural beauty and carefree celebration that seem to epitomize life in the Bathtub, he stops short of romanticizing this existence. Hushpuppy charges through life fearlessly and only rarely displays the tenderness typical of a girl her age, such as a brief but loving conversation with a shirt draped over a kitchen chair that stands in for her absent mother. An undercurrent of nobility and utopia exists in the Bathtub, but Hushpuppy’s childhood reveals the gritty savagery that is much more present. Wink raises his daughter to be a fiercely independent person by making her live in her own dilapidated trailer next to his, and he also teaches her to prepare her own meals, care for their chickens and other animals herself, and fish with her bare hands from the back of their repurposed pickup truck-boat. Zeitlin does not shy away from the more brutal aspects of this style of parenthood, as when Wink beats Hushpuppy any time that she shows emotion, or when she destroys her trailer and nearly kills herself after setting a fire in her kitchen.

But Wink raises his daughter in such a brutal and unrestrained manner precisely because he is aware of the world’s chaotic trajectory towards balance. He wants to ensure Hushpuppy’s survival after he is gone, and her intimate connection to the environment as well as her recognition of the interconnectedness of existence makes her a small but mighty survivor. She holds small birds up to her ear and leans in close to her pig and other large animals so that she can hear their heartbeats, and she has an astute understanding of the Darwinian nature of her existence. “I see that I’m a little piece of a big, big universe,” her narration declares twice during the film, and she has firsthand experience with the frailty of life. In a comment that refers to her father’s growing illness and also the harm that humans are doing to the planet, she says that “the whole universe depends on everything fitting together just right. If one piece busts, even the smallest piece, the entire universe will get busted.” Here, in Zeitlin’s tale from the Gulf frontier of America, he invokes a piece of American environmentalism. Hushpuppy echoes the Western naturalist John Muir, who wrote in “My First Summer in the Sierra,” “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” Such fitting together and hitching is an essential element in Zeitlin’s film because he juxtaposes the pollution from the Delta factory and Hushpuppy’s lessons on global climate change with shots of the polar icecaps melting and crashing into the sea below.

With the echoes of Hurricane Katrina still reverberating in the American consciousness, and in the midst of another hurricane season in the Gulf coast, it’s not hard to envision a supreme connection among every thing on earth. As John Muir goes on to say, “One fancies a heart like our own must be beating in every crystal and cell,” and this vibrant relationship between human and animal and land and water is at the heart of Zeitlin’s film. Hushpuppy’s teacher describes the melting ice caps and rising sea levels by saying that “the fabric of the universe is going to unravel,” but this unraveling is really the forceful exertion of balance being restored. This balance has two catastrophic implications for life in the Bathtub—the Gulf waters rise and inundate the ramshackle homes, and the melting ice releases frozen aurochs back into the world. These ancient creatures are the long extinct ancestors of modern cattle, but “Beasts of the Southern Wild” depicts them as ferociously oversized pigs with large horns. This bit of poetic license allows Zeitlin to depict the monsters as the uncanny ancestors of the pig that Hushpuppy cares for in her yard.

It takes courage to persevere amidst the force of a universe hurtling toward equilibrium, but Hushpuppy is no ordinary girl. She is an introspective and self-reliant child, and she is also the descendant of the no-nonsense small-town child characters of the American literary canon. Hushpuppy’s story, like those of Huck Finn and Scout Finch, is one of forging an identity in a sometimes brutal environment, dwelling in and coming to love a particular place, and fighting for survival in the face of cultural and ecological imbalance. The Bathtub is a community that unabashedly celebrates life because they know that their existence below the levee and above the eroding coast is a threatened one. The same water that provides them with piles of shrimp, crawfish, and catfish will also inevitably rise and destroy them. Amidst this conflict, Hushpuppy and her community actively participate in the film’s ecological conflict. After their home is flooded, Wink and Hushpuppy blow a hole in the levee that drains the water north and floods portions of inland Louisiana. With “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” Zeitlin shows that he is still concerned with environmental destruction and human recovery, as was his focus in “Glory at Sea,” but that he is now widening his gaze beyond one Louisiana community to the level of the global.

The Bathtub is temporarily raised out of the flood, but a tone of inescapable apocalypticism pervades the end of the film. Hushpuppy believes that “sometimes you can break something so bad that it can’t get put back together,” and the viewer is forced to confront this fatalism even as drought, rising temperatures and coastlines, and renewed storm activity buffet our own small piece of the big universe. Zeitlin does not explicitly claim that our world is broken beyond repair, but he does provide an exemplar of survival and vivacity amidst such chaos. Near the end of the film Wink’s illness becomes more debilitating as the aurochs charge across barren landscapes and through towns on a crash-course with the Bathtub, two simultaneous events that threaten to destroy a child’s world, but the final scene shows Hushpuppy and the Bathtub’s survivors marching along the road as rising water laps at their feet. Her narration proudly states that she is recording her story for the scientists in the future: “In a million years, when kids go to school, they’re gonna know. Once there was a Hushpuppy, and she lived with her daddy in the Bathtub.” Hushpuppy’s story is one inspired by a stubborn father, a strong mother, and a community that refuses to cede its place in the universe. Neither flood, nor marauding prehistoric beasts, nor even the end of the world can quench Hushpuppy’s insatiable desire to live.

Justin T. Noetzel teaches at Saint Louis University. His research and publications focus on manuscript studies, space and place theory, ecocriticism, monsters, cultural history, and geography and landscapes in literature. He lives in St. Louis with his wife, two children, and two dogs.

0 comments on “Review: Noetzel”