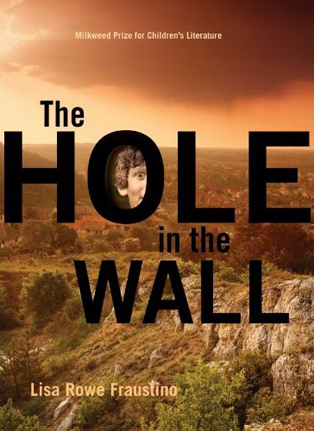

‘The Hole in the Wall’

Meghan McCarron

Lisa Rowe Fraustino, “The Hole in the Wall”

Milkweed Editions

2011, 280 pages, paperback, $17

There is an element in children’s literature that adults often label “fun,” which I would call “immediacy.” At its best, a children’s book dips and soars like a child’s experience of the world. A child-reader finds her experience mirrored and understood; the adult reader re-experiences familiar conundrums as fresh and new, both exciting and frightening. One of the most notable manifestations of this phenomenon is the way children’s books re-define the nature of “home.” As adults, we have learned to imagine home as a static haven. But in children’s literature, it is anything but. “Home” is changeable and unstable, with hidden doorways and secret signs. This paradox, seen in everything from classics like the “Narnia” books to contemporary favorites like “When You Reach Me,” animates children’s literature with a unique sense of place.

In Lisa Rowe Fraustino’s “The Hole in the Wall,” the story is of Sebby, a twelve-year-old boy whose town has been half-destroyed by an unusual strip mine. Many of the town’s residents were bought out to create the mine, and now the runoff is polluting Sebby’s family’s property. The strip mine in “The Hole in the Wall” isn’t for coal; it’s for a magical mineral called adrium. Its properties are never fully defined, but it has the power to inhabit paint, perhaps restore youth, and, in large doses, it turns organic matter to stone. Sebby’s family’s chickens, his older brother, and his father all suffer from serious adrium poisoning. But Sebby has found a bright spot. In the middle of a slag heap, he finds a hidden-away oasis and a cave where colors dance on the walls. He calls it the “Hole in the Wall.”

This summary makes “The Hole in the Wall” sound bleaker than it actually is. In fact, Sebby is an energetic, adventure-loving kid who doesn’t take the portents around him very seriously. He describes a petrified egg he finds thusly: “Instead of going SPLAT! Like a decent egg should, the freak went BUMP!” He and his twin sister, Barbie, hide the eggs away and try to revive them. They sneak into the owner of the mine’s house, and befriend his quirky, elderly mother. They journey deep underground to find more of the sparkling, colorful rock. Sebby steals cookie dough and forgets to turn in his homework and gets into tussles with Barbie.

At its best, Fraustino’s book looks at the cascading effects of strip-mining while still retaining a child-like wonder for the world. The runoff and the secret mineral being mined have myriad bad effects, which are slowly revealed by the damage they cause, from giant killer mold to poisoned groundwater. Furthermore, the mine fractures Sebby’s family. His father, once a master stone mason, can’t find work and takes to drinking. His mother can no longer sell eggs, and she might have to leave the land that has been in his family for generations. His grandmother, called Grum, lives with them now, since her house was bought out by the mine.

Fraustino also does some interesting work with class and how money is used to ease the way for environmentally destructive policies. The mine owner is a childhood friend of Sebby’s Pa, and there is an implication that he discovered the mineral because he spent his childhood exploring the area’s underground caves. His status as a local encourages the townspeople to trust him, but he also offers big buyouts to get people off their land. In one scene, he shows up at Sebby’s house with a pile of cash and offers more if the family wants it. The presence of that money creates a great deal of division within the family, suggesting that the wad of cash will not make them as happy as Pa assumes, especially because they are offered a new house in a development next to the mall, instead of the beautiful land they currently own.

The magical nature of adrium allows Fraustino to create both a more immediate environmental disaster than the usually slow-moving poisoning involved with mines and also a story that feels allegorical rather than preachy. The reader is invited to consider the impact not just of a specific environmental issue but of our general willingness to sacrifice nature and safety in order to extract a “precious” resource. Adrium has some cool properties—the book opens with Sebby’s love for the show of flickering colors it creates along a cave wall—which also complicates the narrative of whether mining adrium is ‘evil’ or ‘good.’ The element can be beautiful, but it also makes an ugly mess.

“The Hole in the Wall” would best suit young readers with a taste for adventure and playfulness who are just being introduced to the concept of environmentalism. The story does have dark elements—the family nearly loses their house, Sebby’s parents split up, and adrium has some frightening side effects—but Fraustino handles them with a light hand, and, at the end of the story, she offers a fairly happy ending. The book, as a result, does not offer the most nuanced look at the long-term effects of environmental devastation, but it offers a playful and balanced introduction.

Meghan McCarron’s short stories have appeared in venues such as Strange Horizons, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, and Clarkesworld. A former Hollywood assistant, boarding school English teacher, and independent bookseller, she is currently getting her MFA at Texas State University.

Meghan McCarron’s short stories have appeared in venues such as Strange Horizons, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, and Clarkesworld. A former Hollywood assistant, boarding school English teacher, and independent bookseller, she is currently getting her MFA at Texas State University.

0 comments on “Review: McCarron”