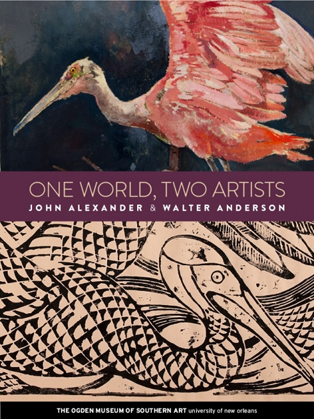

Alexander and Anderson:

The Gulf Coast Seen from Two Perspectives

Emily Howorth

Sue Strachan, Editor, “One World, Two Artists: John Alexander and Walter Anderson”

University Press of Mississippi/Ogden Museum of Southern Art

2011, 90 pages, hardcover, $55

Many say we see what we want to see in the world. Our perceptions and perspectives are inexorably linked. The hang glider’s exhilarating cliff is the acrophobic’s nightmare. The real estate developer’s feast of plenty is the preservationist’s sacred earth. And even two artists born within the same region, within only a few decades of one another, can look across their common landscape and see two wholly different places. Two artists born and raised in the Gulf Coast region, John Alexander and Walter Anderson, reflect this diversity in human perception. At times magical, creepy, holy, and threatening, the Gulf Coast as depicted in “One World, Two Artists”—a collection of their works—is always awe-inspiring.

Many say we see what we want to see in the world. Our perceptions and perspectives are inexorably linked. The hang glider’s exhilarating cliff is the acrophobic’s nightmare. The real estate developer’s feast of plenty is the preservationist’s sacred earth. And even two artists born within the same region, within only a few decades of one another, can look across their common landscape and see two wholly different places. Two artists born and raised in the Gulf Coast region, John Alexander and Walter Anderson, reflect this diversity in human perception. At times magical, creepy, holy, and threatening, the Gulf Coast as depicted in “One World, Two Artists”—a collection of their works—is always awe-inspiring.

Released by the Ogden Museum of Southern Art and printed locally in New Orleans, “One World, Two Artists” includes one hundred and thirty stunning full-color illustrations depicting the wildlife and landscape of the Gulf Coast as interpreted by Anderson and Alexander (as well as related images of flora and fauna). The book also features written contributions from Jimmy Buffet (a collector of both artists and lender to the exhibit), Bill Dunlap, Mark Stevens, Bradley Sumrall, and Annalyn Swan. I recently viewed the excellent accompanying exhibition, also titled “One World, Two Artists,” at the University of Mississippi Museum, in Oxford, Mississippi. (The exhibition will move to the Walter Anderson Museum in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, in January 2012.) Although the book is divided into two sections, with one section devoted to each artist, and although the exhibition similarly displays the work of the artists in separate rooms, as if to resist comparisons, I found it difficult to avoid contrasting the perspectives of Alexander and Anderson when viewing their works.

John Alexander, born in Beaumont, Texas, in 1945, lived in Texas until moving to New York in the late ’70s, where he remains today. The Gulf Coast seen by Alexander is sometimes conveyed through a purely naturalistic point of view but more often is a beautifully dark and somewhat menacing place, filled with interspecies struggle and edgy anthropomorphism. Alexander’s tendency to depict a violent animal kingdom is beautifully wrought in “Herons in Heat,” a spectacularly frenetic and highly linear painting and one that, like most great paintings, carries far more punch in person than in print. But Alexander’s scenes are not always so ferocious. The artist’s sense of humor often comes across in his titles—“Dancing Fool,” “Angry Little Fish,” “Grackle with Blue Balls.” And visual references to Hieronymous Bosch remind us that Alexander sees his world through a very human lens, one versed in history, sensitive to psychology, and aware of nature’s destructive forces. His perspective, one might say, is thought-driven.

Walter Anderson’s Gulf Coast, on the other hand, is a more mystical, spiritual place, alive with brilliant, bright colors and full of patterns—so full of patterns, in fact, that the artist’s devotion to design borders on obsessive. Born in 1903 in New Orleans, and later a resident of Ocean Springs, Mississippi, Walter Anderson was raised in an artistic family and received a formal art education. Struggles with mental illness ultimately led him (with the blessing of his family) to live an isolated life dedicated to the daily practice of his art. Some of the works included in “One World, Two Artists” are artifacts of Anderson’s time spent on the remote Horn Island, a small barrier island about ten miles from Ocean Springs, which Anderson visited almost daily by rowing in a small skiff. One legend has it that, when given a motor for the boat, Anderson used it as an anchor. Another legend recalls Anderson lashing himself to a tree to witness Hurricane Betsy firsthand as it passed over Horn Island—only months before his death. The fearlessness with which he lived and experienced his environment is reflected by the relative tranquility of his perception, such as in the edenic “Father Mississippi.”

Anderson used whatever surfaces he could find to create his watercolors; many of his watercolors included in “One World, Two Artists” are masterpieces captured on simple sheets of typing paper, some of which have burnt edges. It is difficult to resist the conclusion that Anderson was wholly devoted to his personal visual experience of the environment surrounding him, whereas Alexander, perhaps, is more conscious of his audience. Living so close to the muse that was his environment, Walter Anderson was not so much a privileged human observer of nature, but rather viewed his existence as one small link within a sweeping, awesome, natural order.

Emily Howorth lives and writes in Oxford, Mississippi. Her short stories have been published most recently in New Madrid, wigleaf, and in Washington Square Review, as winner of the journal’s 2011 Fiction Award.

0 comments on “Review: Howorth”