Garden of the Goddess:

The Work of Yigal Ozeri

Daniel Levis Keltner

For the last several years, Israeli artist Yigal Ozeri has been painting acclaimed photorealistic works of women in nature. His most recent collection, “Garden of the Gods,” which opened at Mike Weiss Gallery in New York, included more than a dozen such paintings of various sizes, from intimate works displayed in vitrines to large-scale paintings measuring eight feet. Admirers of Ozeri’s work have noted that his subject engages with contemporary theories of femininity and nature. How his work intersects on these fronts is complicated, however, particularly in light of the artist’s intentions.

Ozeri’s aim as a painter is nothing short of idealism, in the most reverent sense of the word. To him, the figures and landscapes that he paints capture the spirit of freedom, and—aided by technique and process—they seek to express true reality. From this vantage, paintings from the “Jessica in the Park” series, for example, serve as character studies that reject interpretation and instead frame a woman named Jessica at transcendent moments, elevating reality from the banal to the romantic. Ozeri’s world is rose-colored.

The artist employs photo-realism to communicate the spirit of the moment—that of a unique person existing at a unique place and point in time—much the same way that film does. In fact, Ozeri paints directly from video stills and photographs that he and his crew take during a shoot with a subject. He performs minor alterations in color and contrast to the snapshots but does not cut and copy elements into or out of a moment. As Shlomi Rabi notes in his essay, “Meditations on the Space in Between,” by re-creating photographs, Ozeri “…breathes life into the fleeting moments that he had captured, challenging the momentary recording of the photograph, turning the temporal to the eternal. The paintings … are not to be read as photorealistic, but rather, as transcending reality, a visual meditation on the soul.”

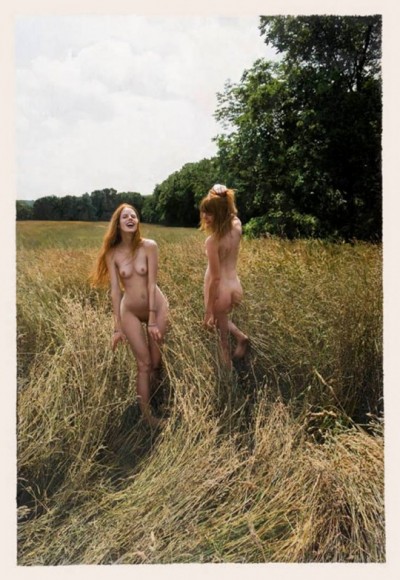

To help capture authentic human experience, Ozeri does not often use professional models. Instead, he paints social wayfarers and other fringe personages met through friends. According to Ozeri, his fascination with the women he paints does not stem from a desire to possess their physical bodies so much as from a desire to convey their spirit. He spends a long time with his subjects, becoming intimate parts of their lives and families as a friend, until he is ready to shoot. Though Ozeri directs his crew at every stage of creation, he never directs models. As he describes his method in reference to the “Jessica and Jana in the Park” series, “I said, ‘OK, I’ll take the camera, and I’ll let you do whatever you want,’ and that’s how we did it. It was very playful. They did what they wanted, what they felt, and it was great. I used a long lens from far away and took thousands of photographs.”

Ozeri sincerely believes in his work’s ability to convey ecstatic human experience. However, by creating such mythic spaces, he perhaps slights his agenda. The world of Ozeri’s paintings, heavenly parks or wheat fields safe enough for young women to lounge around alone either naked or wearing expensive dresses, is detached from a common reality. Instead of portraying the seeming banality of existence like the early photorealists, Ozeri’s technique elevates reality to the romantic, arguably, to the point of being schmaltzy, matching the ambience of a perfume ad. This is because, unlike the world of Robert Betchtle’s “Alamda Gran Torino,” for instance, Ozeri’s world begs us to accept his depiction of the unknown rather than challenge the known.

Ozeri has been greatly influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite painters in both process and product. Not surprisingly, his work has come under fire from critics who view it as continuing a Western tradition of misogynist tropes. The predominantly prostate women of his paintings seem once again to equate femininity with passivity, and their depiction as “desirable (and obtainable)” has been said to align Ozeri’s work with patterns of “male dominance and female submission in which the woman becomes the object of the male gaze. The conjunction of the … Pre-Raphaelite allusions to Ophelia, which represents a weakness in femininity, and the modern high-fashion aesthetic, which connotes women’s objectification, form a structure in which the female is essentially powerless.”

Complicating the politics of his work further, Ozeri effectively genders The World Beyond by intentionally conveying women with mythic qualities. Much like with the romantic-versus-realistic binary, to associate an element with one pole is also to exclude it from another. Therefore, his work’s association of women with transcendence alienates women from the ordinary and leaves the work vulnerable to the same feminist criticisms of Pre-Raphaelite works, regardless of Ozeri’s intentions. In her phenomenology of the art gods of the nineteenth century, Professor Alexandra Karentzos argues that, “In this context [femininity] stands for unfragmented unity, ahistoricity, and timelessness…. The situation of the myth in an archaic primordiality further expands the topographic distance by adding the dimension of time. Through this distance, mythical femininity is marked as the other, the foreign.”

Without intending to condone the implications of these binaries, Ozeri unabashedly plays this card: “I think that two naked women in a big field of wheat is the most complete connection with nature. It’s completely about freedom. It’s completely about celebration.” Ozeri believes that his work is in touch with a true feminine spirit, not creating or alienating it. So much so, in fact, that his 2010 exhibition “Desire for Anima” sought to convey anima, the Jungian concept of feminine inner personality. When asked about the show during an interview, Ozeri said, “People have said for years that the point of view that comes out of my work is that it’s like a woman painted it. … It’s like I come to these girls not like a man with his sexual gaze but as a part of their heads. Like Carl Jung said, there’s a part of a woman in the head of a man. … I really think that it’s happened, after the six or seven years that I’ve been dealing with this subject.” Again, the intentions of the artist become problematic when subjected to a feminist critical reading.

An environmentalist critique of Ozeri’s work lies along similar lines. Because the locale of his photographs is often ambiguous and imbued with a “sense of infinity,” the domain of nature—like that of women—also becomes aligned with The World Beyond, a place that is no place. Much like the Pre-Raphaelites, however, Ozeri’s aim is to celebrate the natural world, not marginalize it. In his paintings, freedom is always the end product of the relationship between a subject and her surroundings—without either, freedom could not exist. It could therefore be argued that Ozeri’s principle subject is neither figure nor landscape but a specific point in time where feminine spirit meets nature.

According to the artist, what he looks for when shooting is “… always the first moment with the model in the natural atmosphere. How the model connects with the natural aspects. Her first interaction with her settings. Her initial timidness [sic], slight reluctant behavior, insecurity, embarrassment, the model’s direct gaze, her openness. Sometimes the model experiences joy from her settings; that is the most important element in my eyes. If it doesn’t happen then the work will never happen.” However, the representations of nature in his paintings seem to argue that such joy and freedom can only be found in un-urbanized arcadia—again, The World Beyond. If so, then nature is consequently robbed of the full breadth of its character, influence, and autonomy in the world of the ordinary, as the aim to elevate and celebrate actually devalues that which is celebrated.

Ozeri’s most pleasantly complicated paintings in terms of environmental binaries are his “Lizzie in the Snow” series. Both Lizzie’s cigarette smoking and the environment’s frigid cold challenge a viewer’s expectations of acceptable behaviors in and by an idyllic natural world. By doing so, the paintings reclaim a unique strength and depth for both Lizzie and her environment. The key difference is that each clearly affects the other—their relationship is two-way, active and not passive.

Yigal Ozeri has grand intentions for his paintings and for art in general. He sees his work as enacting social change, educating audiences by allowing them to experience the antithesis of death and violence. He wants the world to be a better place and sees art as integral to that process. However, no matter how hard the artist strives in his work to convey a subject outside of historical time and space and “… push through to … reality” for the wellbeing of humanity, his gorgeous paintings nevertheless exist in a socio-historical context to which they, inevitably, must account.

Daniel Levis Keltner, Visual Arts Editor

0 comments on “Painting: Ozeri”