Christopher Coake: Polite Midwestern

Hauntings, Tabletop Roleplaying, and

the Nature of Home

Cameron Turner

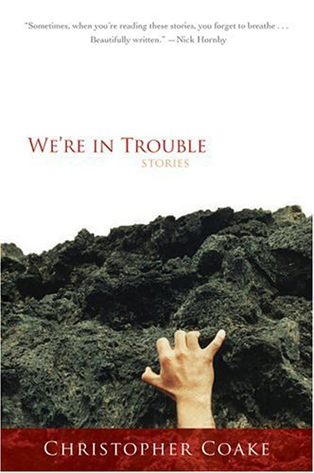

What’s the worst thing that could happen right now? The question followed me around at the heels, rattling like old bones, for weeks after I finished Christopher Coake’s mesmerizing debut collection of short stories, “We’re in Trouble.” Coake’s among the best contemporary writers when it comes to depicting painful baptisms into unexpected (often unwished) clarity and grace. “Abandon,” one of the latter stories in the collection, especially puts its reader through a kind of unanesthetized open-heart surgery as its two characters, outcast lovebirds, face one increasingly dire dilemma after another in a snowbound Michigan cabin as night falls.

But don’t think Coake only writes hyperventilating page-turners: his stories are layered, generous, and human; they speak with conviction and, at times, the kind of wry humor that can arise when confronting death.

Coake, an alum of Ohio State’s MFA program, was awarded the Robert Bingham Fellowship for best debut fiction from PEN American Center in 2006 for “We’re in Trouble,” and Granta named him one of twenty “Best Young American Novelists” in 2007. His writing has appeared in The Gettysburg Review, The Southern Review, Epoch, and Five Points, and was included in “The Best American Mystery Stories 2004,” and he teaches at the University of Nevada, Reno. His first novel, “You Came Back,” is due on shelves in June, 2012.

CAMERON TURNER: Can you talk a little about the process transitioning from “We’re in Trouble” to the project you’ve got on the way?

CHRISTOPHER COAKE: The transition was hell, basically. When I was a teenager, I wrote several novel-length works—fantasy and sci-fi novels, as terrible as can be—so in the back of my head, after I graduated from Ohio State with a book of stories and my MFA, I was sure that I could make the leap from writing short works and novellas (which were what I’d focused on exclusively in my graduate studies) to the Big Project I told everyone (my publisher, my agent, my institution) was just around the corner.

When I sat down to attempt a novel, though, I found out that all my short-story writing habits were inadequate. I was not a write-every-day writer; I also tended, when writing a short story, to produce a lot of pages and then distill them down into the finished work. A novel, though, can’t be written via a few caffeine-fueled all-nighters and a month of revision and prodding. I thought a year or two would be plenty of time … and I was wrong, wrong, wrong. I would have been wrong even if I hadn’t just taken a tenure-track job, gotten remarried, and moved cross-country. But I had done all of those things, and so the first two years of novel-writing were abysmal. I just couldn’t seem to find time or a foothold.

In those years I wrote 100 pages of Failed Novel #1 (an expansion of a story in my collection, about a Slovenian mountaineer and his wife) and 250 pages of Failed Novel #2 (a complex story about a miner in 1890’s Colorado). I did a lot of work toward each that I was proud of, but neither story ever manifested itself in front of me in the way I needed in order to push through to the end. Plus FN #2 required research—much more research than I was comfortable doing at the best of times, and especially while the tenure clock was ticking.

So I abandoned both in favor of the book I did finish. I told myself when I started this third novel that it would be a short project. Then I proceeded to sit down and write the longest work I’ve ever undertaken. The draft Grand Central just purchased is 446 pages long in manuscript form, and I have easily a thousand pages of material I’ve cut from it along the way. Along the way, I turned myself (at least for the sake of this project) into the write-every-day, just-make-the-pile-bigger-no-matter-what sort of writer I never thought I was.

It was tough. The story was tough on me, emotionally and intellectually; and I did the whole thing aware of my institution’s imminent tenure decision. I really and truly hope people love the book as much as Grand Central seems to believe they will, but right now the manuscript seems to me to be soaked in my tears and blood—going into it to make even small revisions feels like visiting an alley where I got beaten up.

TURNER: Are you at liberty to say where it’s set?

COAKE: The new novel is set in Columbus, Ohio, just at the beginning of the current recession. When I moved to Reno, I was excited to begin writing about the West—and then, a couple of years into my stay here, I began to get more homesick/nostalgic for Ohio than I ever dreamed I would when I lived there. Specifically, the setting is my old neighborhood: Victorian Village, just south of Ohio State’s campus, where I rented an apartment during my three years as an MFA student. Every day I’d walk to school past these huge, brick Victorian homes—I spent hours and hours fantasizing about living in one of them. When it occurred to me to write a ghost story, Columbus—and that neighborhood in particular—seemed to be the best possible choice for setting. One, because Columbus—all of the Midwest—has always seemed too polite and boring to be the setting for a horror story, so I thought I’d get some interesting friction out of turning that feeling on its ear; and two, because Victorian Village is so genteel and quiet—and, in certain moods (especially in winter, when my story takes place) spooky enough. The book is trying to subvert certain aspects of the classical ghost story, too—I do get a little kick out of telling my very non-Victorian ghost story in a place called Victorian Village.

I’m not interested in doing what the bioregionalists do. I’m more interested in assessing how place, ‘home,’ affects character. ‘Home’ as defined by human relationships, familial relationships. That’s my material, right there. –Christopher Coake

TURNER: How’s it been to write about Ohio from Reno?

COAKE: It’s not been too difficult or strange. I wrote about a couple of neighborhoods that I knew really well and a city whose layout and character I knew well enough. It’d be one thing, I suppose, if I’d been crafting a memoir set back there; but the fact that I was working with fiction made things a lot easier, just in terms of accuracy. A novelist does get some license, even when writing about a real place. I just wrote an author’s note for the book, though, wherein I tell readers that I took that license—much of the book takes place in a house in my old neighborhood of Victorian Village; but I didn’t have an actual house in mind, so I added a fictional street to the Village and kind of muddled the directions to its door. Another long scene takes place in a real location, the Franklin Park Conservatory, but the characters walk through a kind of alternate-reality version of that building. I’ve been to the Conservatory recently; I took pictures there for reference. But I fudged a little all the same. In the end, I’m not writing about real events, so I felt it was appropriate to place the book’s events in a not-quite-real Columbus that I hope doesn’t piss off actual Columbus residents too much.

TURNER: I wanted to ask about Ohio because, on one hand, among the most zealous of bioregionalists and some environmental writers, even fiction writers, there’s a tendency to glorify writing that’s inseparable from inhabitation. Sending down deep roots in a place and making sure you get all the Linnaean names right. Knowing the geological and biological and cultural history of your place, and so on.

On the other hand, though, I think of Roberto Bolaño’s speech about literature and exile, published in The Nation last January, where he says,

[A] refrain is heard throughout Europe and it’s the refrain of the suffering of exiles, a music composed of complaints and lamentations and a baffling nostalgia. Can one feel nostalgia for the land where one nearly died? Can one feel nostalgia for poverty, intolerance, arrogance, injustice? The refrain, intoned by Latin Americans and also by writers from other impoverished or traumatized regions, insists on nostalgia, on the return to the native land, and to me this has always sounded like a lie. Books are the only homeland of the true writer, books that may sit on shelves or in the memory.Can you speak to the idea of “home” in your fiction—and writing about your own home, however you define it—at this point in your career?

COAKE: Hoo, wow. I love Bolaño, and I love that speech. I don’t know how much I’d like to associate my own writing with its ideas, however. The key phrases for me are “the suffering of exiles”, and “writers from other impoverished or traumatized regions”—which is not referring to me or to Ohio. Bolaño’s making a case—and making it well—for the primacy of the imagination but for reasons that are different and more important than any I’d make, regarding my recent work.

It’s a difficult question. I made my home in Ohio for nearly a decade. I met my first wife there; we married there; she died there, in Columbus, over a decade ago. When I go back to Columbus, I encounter her and our life there everywhere I go; however, when I return to Columbus now, I’m usually doing so in the company of my second wife, visiting her family and our mutual friends and seeing people from Ohio State, whom I met after my first wife died. The book I just wrote deals a lot with this—the idea of having two lives, separated by trauma. My protagonist, like me, built a life for himself twice in Columbus and had to build the second after the destruction of the first. And then I left Ohio for Nevada and built a whole other kind of life here in the West. My protagonist is thinking of doing this, too; and then his first life reappears, in the form of an alleged haunting. I wrote this story in large part because this is a fear of mine, of having to go back, of having to cross the barriers of trauma and relocation.

As a man who’s ‘overcome’ tragedy, all my nightmares are about how I really haven’t. So it’s easy and fair to say the book is about haunting more conceptually. What holds us back? How do we move on? Is our home in place or memory? –Christopher Coake

But I’m dancing around your question a little, and that’s because I’ve never been someone who was sure of what “home” was. I’m American, obviously—an American who until recently had never traveled outside of his homeland. But otherwise I’ve lived the life of a nomad. I’ve changed residences over forty times in my life. My family was always on the move, house to house, state to state (I lived in both Colorado and Indiana as a child). I changed schools every couple of grades until high school. I don’t keep in touch with my extended family, and my close relatives, my mother and sister, have been fairly nomadic too. This makes my reactions to place very different.

Here’s an example. My wife, Stephanie, who was born in raised in the same house and school system and whose family is deeply rooted to Columbus, had a very different reaction to moving west than I did; she found this place kind of fundamentally upsetting, for a while—it was Different. On the other hand, I reacted with more excitement. I’d loved the West as a kid, and wanted to return to it. I was looking forward, and she was looking back; our lives had shaped us to do so.

But then we had to adapt. For the first time, I was looking to settle down permanently. After a childhood of uncertainty and fear and a first marriage full of uncertainty and fear, I wanted badly to be Home. But when I made it—when I was remarried and settled in, when we’d bought our first house—then I became terribly nostalgic for Ohio. Not because we wanted to go back there, but because, for the first time, I could see Ohio as a place I wasn’t dreaming about leaving. I began to get really weirded out by Nevada—maybe because I had no real architecture in place for nesting, settling, being safe.

Stephanie, on the other hand—after some early grief—settled right in. She’s trail-running, she’s engaging with the landscape and community, and so on in ways that I struggled with. (Maybe because, while she was doing these things, I was spending hours every night imagining trauma in Ohio.)

I guess to answer your question more directly: I’m not interested in doing what the bioregionalist types you describe do (though I love writing of that type). I’m more interested in assessing how place, “home,” affects character. I wrote a book that puts a trio of Midwesterners through the wringer, but they’re urban Midwesterners and intellectuals; they’ve grown up inside, in cities, in books. They dream about western landscapes, but it’s all kind of fictional for them. Instead they’re focused on neighborhoods, houses. On “home” as defined by human relationships, familial relationships. That’s my material, right there.

I’m kinda sorta working on a new project right now that’s set here, in Nevada. It will be very intimately about place, but even so, I don’t have any native Nevadans as my protagonists. The character I’m most interested in, in fact, is a Hoosier who finds his way to a very isolated house out in the desert. I’m still nervous about characterizing Nevadans—particularly Northern Nevadans. I live among them, but I’m not one of them. I’ve made a home here, but is it my Home? That I do not yet know.

TURNER: I know what you mean. The average American moves twelve times during a lifetime. I moved constantly as a kid and have spent most of the last few years bouncing from one apartment complex to the next across three states.

And (to make a point that lots of people have made and made much better than I’m about to) many of our most popular “American” stories are about the weirdness of rootlessness and the reinvention of identity. (Don Draper, here’s looking at you.) But, then, this distinct idea of home lends itself easily to disavowing the past, or even suppressing it. Which is one reason I also suspect we’re so culturally enamored with ghost stories.

You brought up your teenage sci-fi and fantasy geekdom and mentioned the haunting in your current book. How do you see your current work in conversation with these “fantastic” genres, or as speculative fiction itself? Was there anything about your physical rootlessness that encouraged you to seek out these kinds of stories when you were younger?

COAKE: I absolutely wanted to be in conversation with some of the books—the types of books—that moved me when I was younger. When I was a kid and an adolescent, I was a complete and utter nerd. I collected (and tried to draw) comic books; I played a lot of Dungeons and Dragons and other fantasy role-playing games; I read shelves and shelves of sci-fi and horror novels (Stephen King and Peter Straub, primarily) and every bulky sword-and-sorcery fantasy trilogy I could get my hands on. It wasn’t until I was in college that I really understood—or even cared—about the literary canon, or about works in a psychological-realist mode. (And the professor who got me to care did so by tricking me into reading Joyce’s “The Dead”—by telling me, truthfully, that it was the greatest ghost story ever written.) When I saw movies, they were made by Stephen Spielberg. When I look back, I can only see how monomaniacal I was about fantasy—I just did not want the real world to intrude on my imagination.

I don’t see much use in distinguishing between genre and literature. A good story is a good story, and a bad one is a bad one. I’ve read ‘literature’ as awful and clichéd as the worst sword-and-sorcery quest tale on the shelves. –Christopher Coake

Certainly, a feeling of personal rootlessness led me to those works—I was struggling to make friends, a lot, or living in isolated parts of Indiana and Colorado where I didn’t have kids my age living down the street, so books were an easy way to engage my brain in play. I have to say, too, that my childhood was pretty fraught—my father and mother were having a lot of trouble, and there was a lot of drink and drugs and violence in the air. Mom took my sister and me away from Dad when I was thirteen, and that was both tough and necessary. So not only did I want and need an escape from my life—I wanted an escape route that bore no resemblance to anything I knew. I remember getting upset when the fantasy I read wandered off the well-trod path into the troubles of the “real” world. (I read “The Shining” when I was twelve, and that book—with its murderous alcoholic and its ghosts and its parental strife—tore my head open in ways I still flinch away from. And there was another book—a fantasy by Katherine Kurtz, I think—in which the male protagonist didn’t get the girl he loved, and I was weepy and depressed about that one for a long time.)

But on the whole, these books still mean the world to me—I can’t think of many books I’ve read as an adult (no matter how brilliant) that have left me as shaken and moved as, say, “The Stand,” or “Watership Down,” or “Dune,” or “The Prydain Chronicles.” Those books set me on my course; and, even if I’ve moved down a different artistic path in my own writing, I don’t see those books as somehow less “good” or “important” than the mainstream-lit stuff I read and aspire to write now. I don’t see much use in distinguishing between genre and literature, either—and in fact I’m amazed at how many people still want to make that distinction. A good story is a good story, and a bad one is a bad one. I’ve read “literature” as awful and clichéd as the worst sword-and-sorcery quest tale on the shelves. And I’ve also read Dennis Lahane and Ursula K. LeGuin and Gene Wolfe and Peter Straub and Guy Gavriel Kay and Richard Adams. Oh, and “The Turn of the Screw” and “Dracula” and “Frankenstein” and “The Handmaid’s Tale” and “1984” and the works of Angela Carter and Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Borges and Cormac McCarthy and so on and so on. So much of what we call “literature” plays with elements of genre that it’s terribly foolish to claim a work that deals with wizards is by its very ambition doomed to failure.

So yes, I’ve been thinking for a long time that I wanted to write a book that hearkened back to the type of stories I enjoyed as a teenager. If anything, I wanted to do something that played with the very sense of a divide between genre and lit because (to shift gears here, maybe paradoxically) even defenders of genre writing tend to read too much within their genre, you know? If you want to claim that genre is literature, great!—but make sure you’re reading books periodically that don’t take place on spaceships, okay? It’s possible to love both Swedish mysteries and “Ulysses.” Anyway—I tried to think of a story that would appeal to people who are distrustful of genre and also to people distrustful of lit. What kind of plot would keep both readers reading?

The new book came together around the idea of a ghost, but my take was that, in my story, the very idea of the ghost would be under attack from its introduction. Whenever I read a traditional horror novel, I always have to suspend my disbelief extra hard when the supernatural makes its appearance—unlike, usually, the characters, who either believe in the ghost kind of weirdly quickly or whose disbelief in the ghost leads them into danger or ruin. I’m an atheist and a rationalist, as much as is possible; and I’ve always imagined that if I was present for some of these plot events, the book would grind to a halt while I kept offering “solutions” that explained the ghost away. So I wondered—how would a ghost story look on the page if one happened to a guy like me?

So then I was off. My book is about a man who has lost his son to a household accident, some years before, and who believes he has overcome his loss (not only of the boy, but also of his marriage, in the accident’s wake). Then, just as the man is getting ready to remarry, he’s contacted by people who live in his old house; and they tell him they believe his son’s ghost is haunting it; and would he please come back and do something about it? The man tries everything he can to disbelieve—but then his ex-wife (whom he still loves and misses) tells him she believes…

It’s a ghost story, and it isn’t. But it is, I think, a horror story more generally—though I’m trying to be subversive, I’m also trying very hard to deal with my own nightmare territory: as a man who’s “overcome” tragedy, all my nightmares are about how I really haven’t. About my first wife showing up at my door, wondering where I’ve been all these years. So it’s easy and fair to say the book is about haunting more conceptually. What holds us back? How do we move on? Is our home in place or memory?

Cameron Turner, Interviews Editor

0 comments on “Interview: Coake”