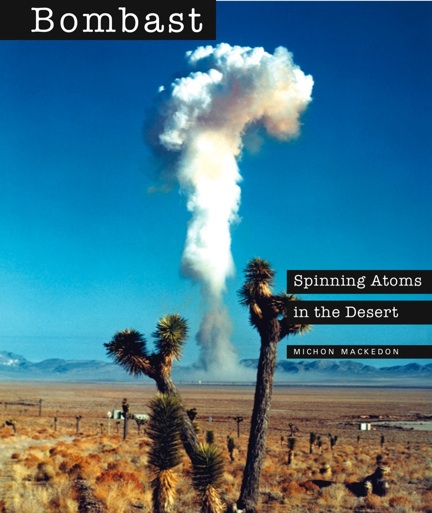

‘Bombast: Spinning Atoms in the Desert’

David Stentiford

Michon Mackedon, “Bombast: Spinning Atoms in the Desert”

Publisher: Black Rock Institute Press

2010, 236 pages, paperback, $30

To spin the atom in the Nevada desert, explains Michon Mackedon—to get people on board with nuclear testing and repository sites—is much more than a scientific endeavor: it’s an art that requires data, predictions, and places to be stitched together with just the right influential language. Part commentary, part rhetorical analysis, “Bombast: Spinning Atoms in the Desert” tells the story of nuclear events related to the Nevada Test Site and the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). The book also explores terrain beyond the NTS to analyze language, cultural artifacts, and other nuclear events that contextualize Nevada’s role as the nation’s principal atomic weapons testing site and, at one point, the potential repository for the country’s high-level radioactive waste. Mackedon, who for twenty years served as a member and vice chairman for the Nevada Commission on Nuclear Projects, tells us how the Nevada Test Site (NTS) and Yucca Mountain were promoted through clever “imagery, euphemism, and promotional rhetoric” that emphasized the naturalness of radiation, touted the clean safety records of tests, characterized the desert as a wasteland, and leveraged the language of “sound science” to achieve questionable ends. This “sound science,” the book argues, masked political interests, and aesthetic and sociological assumptions about Nevada.

“Bombast” shares a lot of information with readers. We learn, for example, how the first American nuclear tests in Alamogordo, New Mexico and the Marshall Islands informed site selection strategies that led to the Nevada Test Site’s establishment. We hear and see how journalists caricatured Nevadans in early reports from the NTS. We learn about the paradoxical job of the AEC: the commission had to pacify atomic testing in the eyes of concerned Nevadans, while at the same time, present a tougher front to the rest of the nation, bolstering public opinion that the atomic weapons detonated in the state could rapidly inflict enough force to destroy people, cities, and the infrastructure of America’s enemies.

In “Bombast,” we’re also oriented to the absurd world of bomb names—for example, Muenster, Colby, and Gouda, from the wine and cheese series of tests—a language game which, Mackedon says, “…distances the object and event from the violent reality of its powers.” We hear how Project Plowshare was used as an innovation (and perhaps propaganda) program to develop atomic explosions for the utilitarian purposes of excavation. We learn about Project Sunshine where radioactive particles were let loose from the Hanford Site in Washington State to track their movements in the atmosphere around the globe. We’re told about Project Plumbbob, a series of civil effects tests where animals (such as Dalmatians), foods (like peanut butter and wheat), and spaces (like the iconic single-family home) were observed to see how nuclear blasts and the resulting fallout might affect civilian life. In a catalogue of cultural artifacts associated with atomic energy and nuclear bombs from the 1960s onward, the familiar day-to-day objects of “Atomic Pop,” the visual centerpiece of the book, remind us how deeply embedded the symbols of nuclear weaponry and waste have become in our consumer culture and material lives. Photographed by Peter Goin, these images show a range of objects and places, from a discontinued Nevada Test Site license plate, Fat Man and Little Boy earrings, and signs for atomic motels, bowling allies, body shops, and laundries located across America to a neutron irradiated souvenir dime from the 1964-65 World’s Fair. “Bombast” also describes how the desert outside the author’s hometown of Fallon, Nevada was used for underground atomic detonations after atmospheric testing was internationally banned in 1963. We hear how Howard Hughes, living on the Las Vegas strip, opposed the NTS; later, we find out, his company became interested in nuclear explosives as a tool for diverting water from Lake Mead to the city. We learn that the original idea for Yucca Mountain was that the region’s geology would sufficiently contain the waste, yet, when this proved implausible, designing safety barriers became the new focus of the project. “Bombast” further suggests that the scientific predictions and modeling done for the Yucca Mountain site—attempts that try to envision geologic scenarios several hundred thousand years into the future—are scientific shots in the dark. And, finally, the book guides us through a brief history of cultural productions—from candy to films to literature and atomic tourism—that express an odd American fascination with the lethal power and toxicity of atomic bombs and nuclear waste.

Who might find “Bombast” interesting? Nevadans, certainly. While the scope of this book goes beyond the state, its points of inquiry remain strongly connected to the region. “Bombast” works to investigate how Nevada’s deserts came to be connected with nuclear projects, and ultimately, how “official rhetoric [was] used to pull the wool over our eyes,” as Mackedon puts it. The book has a vested interest in Nevada, to be sure, and I think many of its readers will share that interest. The book will also appeal, from my view, to those interested in environmental history, language, and pop culture. For those concerned with the future of the modern American West, “Bombast” deals with some of the fundamental perceptual issues faced by this vast arid region. This book isn’t an exhaustive history nor is it a quantitative discourse analysis of policy documents. It’s written in language that makes complex ideas available and clear.

“Bombast” faces a few challenges, however, when reaching out to its audience: How does one make serious rhetorical analysis appealing to a general readership? How does one refrain from turning a discussion on such loaded topics into a polemic? To the first question, this book has a good answer. Mackedon foregrounds events in her story, providing readers with a narrative through-line to contextualize the language work she does. Mackedon also draws on cultural theory in practical ways, applying a range of interesting ideas (from thinkers such as Michel Foucault, Jürgen Habermas, Edward Said, and Elaine Scarry) to help readers consider the often-overlooked relationship between language and power. The book’s approach to the second question, however, is less deft, and understandably so. The tone of “Bombast” is frequently tongue-in-cheek, and, from this reader’s view, the defensible arguments and definable positions implicit in Mackedon’s work get cloudy in literary metaphor and turns of phrase coated with sarcasm. In places, the arguments of “Bombast” remain just a few words shy of full articulation. The book’s strength is a sharp eye for the ironic events in the atomic history of Nevada; its weakness, I think, is that it responds to the fallacious rhetoric it finds with a counter dose of wittiness rather than plain-language reasoning.

“Bombast” appears sixty years after the first atomic weapons were exploded in the Silver State and comes out alongside two other notable books on Yucca Mountain and nuclear testing in Nevada: John D’Agata’s About A Mountain (2010) and Ann Ronald’s Friendly Fallout 1953 (2010). Mackedon brings to this conversation the dismantled remnants of euphemism and the deadly images that remain alive in our visual sphere. “Bombast” is a necessary reminder of how these words and images made such a history possible, and it’s an unsettling reminder of what it means that this language and these symbols live on every time we pop an Atomic Fireball jawbreaker into our mouths.

David Stentiford teaches developmental writing at the University of Nevada, Reno.

0 comments on “Review: Stentiford”