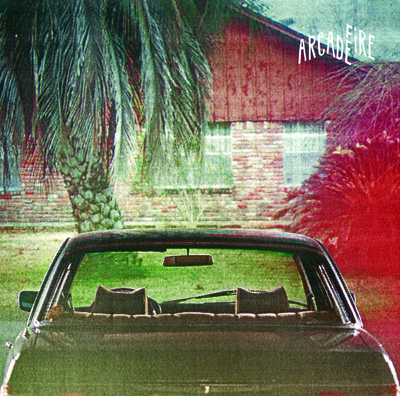

‘The Suburbs,’ Revisited

Daniel Levis Keltner

Arcade Fire, “The Suburbs”

Merge Records

2010, 16 tracks, multi-format

Among intellectuals and high school nonconformists alike, the suburbs, as a physical and cultural entity, have received a pretty bad rap. For as long as they’ve been around, the ‘burbs have suffered critiques by high art as breeding grounds of conformity and complacency, their streets sans inspiration, their denizens sans depth.

Responding to renewed anti-suburbanism in 2009 that followed the release of the film adaptation of “Revolutionary Road,” Lee Seigel documented the history of American suburb bashing in his article “Why Does Hollywood Hate the Suburbs?” According to Seigel, these portrayals hinge on the belief that for anguished suburbanites the “environment has played in the disintegration of their lives.” The principle argument? That suburban living—prefab housing, auto-friendly roads, and strip malls—leaves people confused, emotionally hollow, and grappling with inauthenticity.

So, how do you grow up in such a place and win the Grammy Award for Album of the Year?

Arcade Fire’s acclaimed album, “The Suburbs,” captures both the tragedy and splendor of growing up in a place that is at once everyplace and no place. The album trumps a mere collection of clichéd anthems of malcontent by forgoing pure critique and staying focused on the honest evocation of physical and psychological suburban landscapes.

Mike Diver, writing for the BBC, compared “The Suburbs” to Radiohead’s “OK Computer,” stating, “It’s arguably better.” Whether or not it’s a better rock album misses the heavier question (yes, “heavier”—we’re talking about life in the suburbs here) of whether the message of “The Suburbs” differs any from similar albums that, as one reviewer described, make “epic outpourings of modern disillusionment and disappointment for people who can commiserate and return to fretting about their jobs and bank accounts once the house lights go up.”

Short answer: Yes. Long answer: No, but ultimately Yes. As Arcade Fire front man Win Butler has been quoted, the album “is neither a love letter to, nor an indictment of, the suburbs—it’s a letter from the suburbs.” In short, the record avoids a purely bitter portrayal by expressing what many suburbanites know and feel, both those moments that exalt the place they were born and those moments that make them wish they were born elsewhere. To achieve this, the band wields four cliché-kickin’ techniques.

The Good Old Days

The emotional landscape of “The Suburbs” avoids solely relying on stock feelings of emptiness, social disconnection, and general malaise that records like “OK Computer” brilliantly capture. The mood is not stricken, isolated, defeated, but instead youthful, kinetic, and striving. Arcade Fire largely avoids a one-note portrayal, however, by remaining, what reviewer Vish Khanna calls “cynically nostalgic” of urban sprawl.

Throughout “The Suburbs” we do bear witness to the discontented suburban consciousness: Kids are prisoners on busses by day, free only on their bikes in the streets by night, warring along lines of musical taste, and “[w]ishing [they] were anywhere but here” (evoking cool kid favorite, Pink Floyd). But in the recollection of these moments there is no blaming of “the system,” no desire that childhood be any different (although there’s fear it’ll change), no regrets. In fact, the band makes nostalgia the overarching theme through the framing device of entitling two tracks “The Suburbs.” The first introduces motifs that the bulk of the album then defines, analyzes, and complicates. The last track concludes our trip down memory lane. The final word on growing up in the ‘burbs? Nostalgia. Butler sings, “If I could have it back / All the time that we wasted … You know I’d love to waste it again / Waste it again and again and again.”

What Big Ideas You Have

That’s not to say that “The Suburbs” does not wield any stock criticisms of suburbanism. The most prevalent is the belief that the environment’s design negatively impacts the quality of one’s life. As Butler says on more than one track, “First they built the road then they built the town / That’s why we’re still driving around and around.” Again, the argument is that place has psychological repercussions.

Arcade Fire rises above reiterating such clichés by relying on greater depth of observation. These remarks reflect on the effects of living in a place where driving around an ever changing hometown is the norm and the streets seem to change while we sleep. Lyrics like, “This town’s so strange / They built it to change,” most directly recall Win Butler and Régine Chassagne’s attempt to revisit their childhood neighborhoods, which inspired the album. They discovered that the places where they had grown up were no longer there. In a recent interview with the Montreal Gazette, Butler described that moment: “My hometown left with the people. It’s someone else’s town now … it’s not my town.” As this album consistently reminds us, due to the fact that the suburbs often do not retain a rigid, and so memorable, shape due to constant development and redevelopment, memories are all that remain of these childhood spaces, and even they fade with time. These sentiments are ultimately truer than the communiqués of more socially conscious albums because they are the result of maturity, not idealism.

Tempering the album’s more bleak observations are those of hope and healthy self-doubt, also made possible with age. The track “We Used to Wait” expresses discomfort with the speed of modern life compared to the languidness of the past—a point that, handled by a lesser band, might turn into a good deal of bitching about the good old days. Instead, the speaker becomes aware of and focuses on an unfulfilled, lifelong desire for authentic connection. Allowing oneself to remain paralyzed (recalling T.S. Elliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”) is then forsaken when Butler sings, “Like a patient on a table / I want to walk again / Going to move through the pain.” The speaker hopes that despite the fact times are changing, something vital will endure on into the future. Interestingly, the speaker’s “Hope that something pure can last” also remains non-accusatory, despite the sense of impending doom by forces seemingly outside of one’s control: “So can you understand / Why I want a daughter while I’m still young? / I want to hold her hand / And show her some beauty / Before all this damage is done.”

In addition, Arcade Fire curbs its didacticism in “Modern Man,” which again expresses a dissatisfaction with modernity, with a healthy dose of self-doubt: “You never trust a millionaire quoting the sermon on the mount / I used to think I was not like them but I’m beginning to have my doubts / My doubts about it.” In moments like these, Arcade Fire allows for the possibility that they may not have all the answers, which prevents them from singing the same old song (Radiohead’s “No Surprises” comes to mind) and exhibits a more mature point of view.

The Wilderness Downtown

Whether you like it or not, the album’s trash talking of city kids also helps save “The Suburbs” from advancing the stereotype of its namesake as the most wretched place on Earth. By poking fun at The City as a place of affected depth, Arcade Fire avoids the creation of binaries; i.e. the ‘burbs equal suffering and the big city equals salvation. The band’s criticism of The City smites the trope of cities serving as refuges for individuality and high-mindedness, as noted in Seigel’s Wall Street Journal article. Arcade Fire portrays The City as a place of “modern kids” with their own brand of hipster conformity, their minds filled with faux intelligence, their hearts full of faux passion. Such criticisms are far from being “bitter and deeply resentful,” however, and manage to remain as cute as they are biting: “So much pain for someone so young well / I know it’s heavy I know it ain’t light / But how you going to lift it with your arms folded tight?” Such remarks also reflect back positively on suburbanites—well, other than being jerks in this instance—who must, by contrast, live in an environment that is less affected, less adverse, and less pretentious, regardless if those values are culturally reinforced or not.

The Last Defender of The Sprawl

Similarly, tracks like “Ready to Start” and Empty Room” highlight the gains, albeit meager, of growing up in the ‘burbs. Despite the isolation, meaningless feuds, boredom, and “Dead shopping malls [rising] like mountains beyond mountains,” angsty suburbanites are portrayed as possessing perseverance and, in the act of persevering, fortitude.

This theme culminates in the last major song of the album, “The Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains).” The electro-pop energy of this track combined with Chassagne’s impassioned vocals lend the lyrical image of a young Chassagne being lectured “to stop singing,” a strength beyond strength, especially considering her band’s success. When she sings the final line of the chorus, “I need the darkness, someone please cut the lights,” it’s enough for listeners to believe that it just might happen, the song’s dark and glittering finale that full of power, inspiration, and brilliance. That is how suburbanites win Grammy Awards.

Not all praise or all burn, “The Suburbs” defies stereotypes and expectations while reclaiming the worth of the suburbs as a place where monotony urges one to true existential crisis. As Exclaim! writer Andrea Warner said, the record is “a perfect actualization of the suburbs as metaphor for the classic North American dream: a smoothly perfect veneer covering up the lush complexity of motivation.” According to “The Suburbs,” at the core of this motivation exists a need for authenticity, individuality, and fellowship. Arcade Fire reminds us that, if it is not the transitory environment itself, it is the seriousness of the angst instigated by the place that allows the suburbs to rival any other place on Earth.

Check out the “We Used to Wait” video that costars your hometown: http://www.thewildernessdowntown.com/

Daniel Levis Keltner, Visual Arts Editor

0 comments on “Review: Keltner”