Reality, Surreality, and the

Limitlessness of a Limited Form:

An Interview with Tara Isabel Zambrano

by Margo Orlando Littell

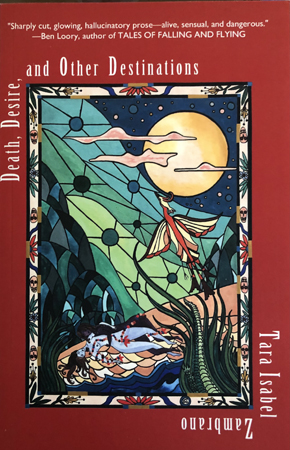

Reality and surreality, the world we know and worlds we’ll never know—the tactile and the fantastical play out across the stories in “Death, Desire, and Other Destinations” (Okay Donkey, 2020), Tara Isabel Zambrano’s debut collection of flash fiction. The stories may be short, but their impact is deep, and Zambrano propels her characters through dreamscapes without pausing for breath—forgoing meandering explanations in favor of dropping readers in and trusting them to find their footing, quickly. This sense of masterful authorial guidance gives the fifty stories in this collection energy and surety. Love, sex, death, grief, motherhood—this collection confronts these and other subjects without flinching, and even the wildest tales are grounded by attention to the earthy, domestic details that unite us all.

Reality and surreality, the world we know and worlds we’ll never know—the tactile and the fantastical play out across the stories in “Death, Desire, and Other Destinations” (Okay Donkey, 2020), Tara Isabel Zambrano’s debut collection of flash fiction. The stories may be short, but their impact is deep, and Zambrano propels her characters through dreamscapes without pausing for breath—forgoing meandering explanations in favor of dropping readers in and trusting them to find their footing, quickly. This sense of masterful authorial guidance gives the fifty stories in this collection energy and surety. Love, sex, death, grief, motherhood—this collection confronts these and other subjects without flinching, and even the wildest tales are grounded by attention to the earthy, domestic details that unite us all.

Tara Isabel Zambrano moved from India to the United States two decades ago and works as a semiconductor chip designer in Texas. “Death, Desire, and Other Destinations” is her first collection. Here she talks with Margo Orlando Littell about the boundaries and freedom of flash, and the particular obsessions that fuel this collection.

We are ready to be startled by the void, the cramped spaceship, to be together on something so far removed from remembering to put the trashcans out on Wednesdays, hating neighbors who didn’t approve of us as a couple, alternating between CBD and Melatonin, waiting for IVF to work.

—Tara Isabel Zambrano, from “Lunar Love”

MARGO ORLANDO LITTELL: The worlds of your stories aren’t limited by any earthly boundaries—“Lunar Love” is even set on the moon. And yet the actual space your stories take up is bound by the parameters of flash fiction. Can you speak to the contrast between the vast landscapes of your subjects, and the constraints of their form? How do you use this disjunct to create the emotional punch of your stories?

TARA ISABEL ZAMBRANO: Margo, thanks for taking time to read my flash collection and crafting these wonderful questions.

I think the limited space of flash establishes the exciting contrast that impacts the expansive worlds in my stories—to enter the grandeur of a cosmos and make your way into the most delicate moments of love and loss. This exercise requires me to pick up details that matter and transport the readers to the right space-time coordinate of heart and body, of experience and imagination. I use the techniques of contracting and expanding the landscapes depending on the central theme of my story. For example, in “Lunar Love,” the title has the moon and the emotion of love in it, so it sets the location and the scope of this piece—but that’s only the background. At its heart, this flash is all about feelings/memories of attachment, belonging. In some ways, you can interpret the travel to the moon as a metaphor for discovering the boundaries and limits of a relationship beyond a physical body. That is the underlying punch.

LITTELL: With stories like “Lunar Love,” which involves travel to the moon; “Scooped-Out Chest,” featuring a disembodied heart; and “the shrinking circle,” in which God plays video games with the narrator, your stories don’t have a lot of time for staid domesticity. Yet in many cases the trappings of domestic life anchor your stories, sometimes absurdly, sometimes powerfully. A woman thinks about putting out the trash and mowing the lawn as she journeys to and from the moon. The disembodied heart is taken to the grocery store. While God sits nearby, a character microwaves ham and cheese. How do you approach the interplay of bland reality with the speculative elements of these stories?

LITTELL: With stories like “Lunar Love,” which involves travel to the moon; “Scooped-Out Chest,” featuring a disembodied heart; and “the shrinking circle,” in which God plays video games with the narrator, your stories don’t have a lot of time for staid domesticity. Yet in many cases the trappings of domestic life anchor your stories, sometimes absurdly, sometimes powerfully. A woman thinks about putting out the trash and mowing the lawn as she journeys to and from the moon. The disembodied heart is taken to the grocery store. While God sits nearby, a character microwaves ham and cheese. How do you approach the interplay of bland reality with the speculative elements of these stories?

ZAMBRANO: Speculative elements in my stories are hooks to pull in readers, offering them the possibility of encountering the bizarre, to pique their curiosity. But, like all good stories, they need gravity; they need strong stakes in the ground to hold the tent that’s flapping in a strange, uncertain wind. And that’s where the mundane intersects with the bizarre. Lots of editing and reworking the sequence of such pieces is required to give them the seamlessness they need, to make them believable, to let them sink and then emerge as something new yet familiar.

LITTELL: The title of your work, “Death, Desire, and Other Destinations,” specifies two “destinations” but leaves the rest to our own interpretations. What other destinations do your stories explore? Might you argue that some of these stories offer the very opposite of a finite arrival?

ZAMBRANO: The other destinations reveal the distance and the milestones, the inchstones between desire and death. Some of the stories feature physical destinations and hence a journey, such as in “Lunar Love” and “Alligators.” In “Wherever, Whenever,” the search for a destination is still ongoing. That state of mind is a pause, a time when you wait for something to arrive in your life—a place, a person, or a clarity that gives your life a location of some sort. It’s an affirmation: yes, I am here, and I will be here for a while. And to answer your second question, it is that clarity I am after more than anything else. Yes, you are right, there are no bounds to it. My stories often reflect an understanding of a destination rather than a destination itself.

Abandoned, I hold on to the shape her body has left behind in me, part home, part grave.

—Tara Isabel Zambrano, from “Alligators”

LITTELL: The dead are often present and animated in your work, either as “a hungry shadow” in “Alligators” or, more dramatically, as a group of dead girls in “Girl Loss,” who wrestle with the fact of their own death as they roam. Death is an end point, these stories suggest, but the dead don’t simply disappear. What does the persistence of the dead say about the living in this collection?

ZAMBRANO: I have been curious about death for a long time now, and I have investigated many questions in my head over the span of several years: What does it mean to die? Is it to disappear, is to linger in the background, is it to be transformed into another form even if it means causing someone’s loss and grief? So far, I’ve found that all of the above are correct. I don’t think the disappearance of a physical body is an end point, even though it might seem so. The longing to have a physical body might sharpen the pain and, eventually, require the understanding to move on, but those are mechanisms to deal with the loss as we comprehend it with our five senses.

I have tried to keep the dead as alive as I can, and I have tried to push the living toward death, because I want to blur these lines of finality. I want to explore the duality in our existence. By “existence” I don’t just mean breathing; I also mean living in someone’s memory. After all, we can only say, with certainty, we are alive in this moment. The past is a memory, and the future is a figment of our imagination.

I have never seen this side of night when you were around. We always slept early, got up early. Yoga, meditation retreats. Understanding the way to live, to die. Now, here on the sidewalk, is a world I haven’t witnessed in a long time. It’s careless, alive.

—Tara Isabel Zambrano, from “Spaceman”

LITTELL: Grief is a recurring theme in this collection, as characters in stories like “Spaceman,” “Whatever Remains,” and “Between Not Much and Nothing” mourn and question and exhibit their grief in ways that make others uncomfortable. Indeed, the grieving people in your stories seem mired in this fraught state, unable or unwilling to see beyond it. Grief seems, perhaps, like one of the “other destinations” of the title. Can you speak to this idea of grief as a distinct mode of existence?

ZAMBRANO: I have known grief for a while now; it’s an old friend. “Other destinations” could certainly apply to it. Years before my father’s death, if someone had told me about the weight of grief, I would have laughed it off. After all, death is a natural phenomenon. We all know we are born to die, so what’s the fuss? But after my father’s demise, I understood what loss meant, and how personal it was. My mother, my brother, and I were all going through the loss of that same person in our lives, simultaneously, but we could realize only our own grief. That’s when I realized the uniqueness of grief, its extent, and its ability to transform each of us distinctly, based on our experience and understanding of it.

And like a torn page from a history book, I try to anticipate what might come after you. It’s like watching dappled sunlight play across a dense forest floor, not knowing which leaf will blaze and which will stay in shade, hoping to be discovered.

—Tara Isabel Zambrano, from “What Might Come After You”

LITTELL: The desire for motherhood is threaded throughout these stories, from the women anticipating IVF in “Lunar Love,” to the woman in “Piecing” whose desperation to get pregnant leads to gruesome, anxious dreams, to the woman in “Spawn” whose longing for a child compels her to push a bunny in a stroller. For some of your characters, motherhood is a destination that seems impossible to reach, and the journey itself holds a kind of permanence. Why do you think your stories explore the longing to be a mother, more than actual motherhood and mothering?

ZAMBRANO: I am so glad that you observe the subtle yet important distinction between longing to be a mother and motherhood. There was a time when I desperately wanted a child, and it didn’t happen right away. Some of this longing is a translation of that feeling I held so strongly, even if it was for a short period of time. The desire to be a mother is still focused on the mother, but motherhood, I believe, takes away a large part of that focus to the well-being and care of the child. I wanted to explore the former in “Piecing,” “Spawn,” and “Lunar Love.” There are other stories in this collection where motherhood is explored, but as expected, it’s on a different spectrum, with a different focus.

Fidgety in their skin, they conclude they’ve died without living. They’re still dying. They call out their names, watch the dust bury their words in the hungry earth.

—Tara Isabel Zambrano, from “Girl Loss”

LITTELL: Sex and love are all-consuming in stories like “In Its Entire Splendor,” “The Moons of Jupiter,” and “Poison Damsels in Rajiji’s Harem,” resulting in women and men who are physically subsumed or diminished, even killed. Yet this seeming violence isn’t always completely negative—in the aftermath, there is also revitalization, safety, and warmth. In many ways, sex and love are related to both death and desire, as though the act of partnering brings its own kind of finality. Has this theme always been a focus of your work?

ZAMBRANO: I have been intrigued by the finality of death, and as a result I have become warmer, softer in my relationships after the hurt, the understanding. That warmth in living has brought forth the revitalization and safety of a moment, of a memory. I see every action converging toward the goal of going back to the basics and starting over, so that has become an integral part of my work.

LITTELL: My favorite story in this collection is “We’re Waiting to Hear Our Names.” I love the easy and swift movement of time; the laser focus on domestic wonder; and the way the very smallest moments, rendered line by line, build an entire life for this couple. So much of their life involves waiting and dreaming, yet there are agency and action too, as the couple create and care for a family and each other. Would you talk a little about what inspired this particular story?

ZAMBRANO: Thank you. Several readers have said the same thing about this story. It’s inspired partly by my life and the lives around me, their domesticity and what it means to be in love and watch its evolution. Even after attaining whatever you want in this life, you feel a prick of that loneliness, that absurd longing for the past and youth and what it should be versus what it is. In some ways, it’s a struggle to live, to strive for happiness and be bombarded with disappointment because you haven’t come to terms with reality, which is often a steady, mundane flow of events rather than something exciting or devastating.

LITTELL: Tara, can you tell us how you came to fiction writing, and what drew you—and continues to draw you—to the flash form? Can you tell us about your journey to publishing these pieces as a collection? And I’d love to hear what you’re working on now.

ZAMBRANO: I started writing poetry in Hindi when I was about nine years old and slowly drifted to stories thereafter. I stumbled upon flash fiction on a workshop site called Fictionaut, and I found this style super convenient given that I work as an electrical design engineer as my day job. I started writing fragments of what could have been longer stories, catching on an emotion, exploring its causes and effects. When I started gathering them in a book-length collection, I interrogated what my stories were about. Longing, love, loss. And once that was established, it wasn’t hard to sequence them. These are stories that have been published from 2014 until early this year. For now, I am writing a lot of flash, some poetry, and thinking about maybe expanding some of the published flash pieces into short stories and coming up with a collection. Maybe a novel.

Margo Orlando Littell, Interviews Editor