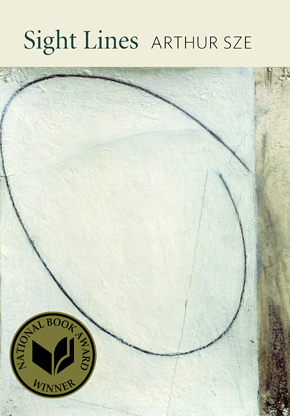

‘Sight Lines’

A review by Deborah Bacharach

Arthur Sze, “Sight Lines”

Copper Canyon Press, 2019

67 pages, softcover, $16.00

Arthur Sze’s National Book Award winner, “Sight Lines,” leaps between images to ask fundamental questions: where are we and what can we can see from here? The work to go on the journey with him, to be summoned by the long lines, long poems, dashes, and cross-outs, is well worth it. In just one poem, I found myself in downtown Shanghai, an arroyo in the desert, and a Spanish forest. Sze takes us to where fires rage and where plutonium lies perhaps not buried well enough. And while we are there, he asks us to consider the power of changing perspective and the lines of sight that can lead to revelation.

Arthur Sze’s National Book Award winner, “Sight Lines,” leaps between images to ask fundamental questions: where are we and what can we can see from here? The work to go on the journey with him, to be summoned by the long lines, long poems, dashes, and cross-outs, is well worth it. In just one poem, I found myself in downtown Shanghai, an arroyo in the desert, and a Spanish forest. Sze takes us to where fires rage and where plutonium lies perhaps not buried well enough. And while we are there, he asks us to consider the power of changing perspective and the lines of sight that can lead to revelation.

Juxtaposition serves him well to create that sliding vision, to show how perspective changes the entire meaning of what you see. In the very first line of “Water Calligraphy” the ten page, seven sectioned poem that starts the book, he writes:

A green turtle in broth is brought to the table—

I stare at an irregular formation of rocks

above a pond and spot, on the water’s

surface, a moon.

So, from one perspective the rocks are just rocks in a pond, but by putting them next to the turtle soup, they are also that which is fragile in our world, that which we so obliviously consume. And then by bringing in the moon, the perspective changes once again. So, what is beautiful and in peril extends to the cosmos. By using a dash between one image and the next, Sze implies that some connective tissue has been left out. He asks the reader to make the leap and see the abutting images as analogy and trusts the reader to draw connections without lots of piddling words like “in the same way as.”

Sze ends many lines with dashes, sometimes every line in a section as in “Python Skin” where each line is also a stand-alone stanza:

flitting to the honeysuckle, a white butterfly—

when she scribbles a few phrases by candlelight, a peony buds—

two does bound up from the apple orchard—

The dash with the accompanying white space creates a big pause, an empty space so the lines cannot blur into one another, and as he says of ants in “Python Skin”: “their channels of empty spaces extend vital breath.” So much breath in these lines. They make me feel unsettled, like there is more to come, more unsaid like a “and yet” moment. The book in fact ends with a dash, so it really doesn’t end. His dashes ask the reader to live with mystery and create connection.

Sze also asks us to play close attention to make those connections. The five sectioned poem “Python Skin” ends “in the sky, not shred of cloud.” The lovers are happy. Everything in the natural world is happy. Except, four pages earlier in the poem we learned “seeding a cloud / is never a cure,” so, in fact, a rainless sky is a serious problem. We are not happily ever after. We are in grave danger. I got strong images and a whole world from a first reading of these poems, but I got a much bigger philosophical discussion from slower careful readings.

Big philosophical questions like how should we live on this earth or as he asks in “Westbourne Street,”: “but what line of sight leads to revelation?” In “Cloud Hands,” the poem that directly follows this one, Sze offers one answer. The woman doing t’ai chi focuses “in the near distance, on the music / of sycamore leaves.” She changes her focus, looks out, looks at nature and by doing so, she is calm and centered even as so much complex life happens around her. Sze returns often to this theme of anchoring yourself and looking out at and through nature as he says in “The Far Norway Maples”: “If you inhale and spore this moment, / it tumors your body, but if you exhale it, / you dissolve midnight and noon; sunlight” I love this promise that you don’t have to hold on to the worst moments. You can exhale them. You can find the sight line to the sunlight, which bursts free at the end of the line.

But, I have to go back to the verbs. Every time I read “spore this moment,” I choke as I feel the fungi like growth spreading through my lungs. He constantly uses verbs in powerful and unexpected ways. In “First Snow” he tells us “a carpenter scribed a plank along a curved stone wall.” Oh, laying the board down with craft and care of a storyteller. When he writes of a beloved, “I’ve listened to the scroll and unscroll of your breath” the lines carried so many connotations—the she as the holder of wisdom, the she as the font of knowledge, breath and book knowledge tied—all brought forth by verbs.

I’ve often read books that felt like a story where each poem added characters or plot, and I’ve certainly read books where the poems flowed into each other making a cohesive whole, but I don’t think I’ve ever read one where I so clearly felt the book was one big poem. Sze encourages that understanding by making really long poems (two are nine pages) using dashes to extend the line into infinity, and spreading lines from the title poem throughout the book. So, the line “—During the Cultural Revolution, a boy saw his mother shot by a firing squad—” stands alone on page eighteen, and from its positioning and how it is written in italics in the table of contents, it seems like a section header. The dashes on both sides of the line (as well as the entire page of white space) highlight the line and position it both as important and a brief interruption. However, the line reappears in the first section of the title poem “Sight Lines,” this time with only a dash at the end. It is embedded in a series of lines that were on their own but now coalesce into one poem, as does this whole visionary book.

Deborah Bacharach is the author of “Shake and Tremor” (Grayson Books, 2021) and “After I Stop Lying” (Cherry Grove Collections, 2015). She received a 2020 Pushcart honorable mention and has been published in journals such as The Adroit Journal, Poetry Ireland Review, Vallum, The Carolina Quarterly, and The Southampton Review, among many others.