Somehow We Control the Narrative:

An Interview with Hayley Krischer

by Karin Cecile Davidson

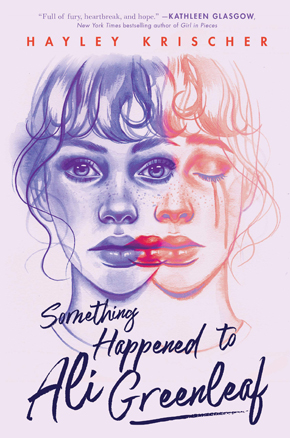

Hayley Krischer’s debut novel, “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf” (Razorbill, October 2020), is a phenomenal look inside the minds of two high school girls—Ali, who has been sexually assaulted, and Blythe, who makes her way into Ali’s world with the intent of protecting the assailant. Straightforward and unflinching, the story leaps into emotional territory, traversing a landscape of best friends, high school cliques, crushes, drugs, parties, bullying, and outright sexual violence against young girls. In a voice that is searing, honest, and original, Krischer has arrived inside the world of YA novels with a topic that deserves serious attention.

Hayley Krischer’s debut novel, “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf” (Razorbill, October 2020), is a phenomenal look inside the minds of two high school girls—Ali, who has been sexually assaulted, and Blythe, who makes her way into Ali’s world with the intent of protecting the assailant. Straightforward and unflinching, the story leaps into emotional territory, traversing a landscape of best friends, high school cliques, crushes, drugs, parties, bullying, and outright sexual violence against young girls. In a voice that is searing, honest, and original, Krischer has arrived inside the world of YA novels with a topic that deserves serious attention.

A journalist for the past 20 years, Hayley Krischer has contributed to The New York Times, The Atlantic, Marie Claire, Lenney Letter, and elsewhere. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from Lesley University.

Some nights it seems like the world has its arms wide open, that the future sizzles with possibility.

—Hayley Krischer, Blythe in “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf”

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: The opening line of “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf” is an invitation to a dangerous place, and yet comes across as intriguing, dazzling, filled with hope. There is a sparkling energy in the language, one of youth and what this night might bring. Here, we are in Blythe’s viewpoint, and soon that perspective will shift to Ali, the novel pared down to these two voices.

Tell us about these two voices and the decision to create an entire novel around them.

HAYLEY KRISCHER: Originally my book started with one voice. That was Ali. I started writing this back when I was in college, over 20 years ago. It started as a short story about a girl who was raped. The scene was very similar to the one that is in the book now. And over the years I kept coming back to the story. I was still drawn to it so many years later that I thought I owed it to the story to explore it more. So I did. I turned it into a novel and then very luckily found an agent who loved it and became a huge champion for me. Someone I really trusted. Still, something about the novel wasn’t working. I had written Blythe as this one-dimensional villain and it wasn’t sitting well with me. This was around the time R.J. Palacio’s “Wonder” came out, which my son was reading and loved. There was an accompanying piece about Julian, the bully of the story, called “The Julian Papers,” which explored what would spur Julian to bully a boy with an eye deformity. And guess what? Julian had a lot of problems! Then I had an epiphany. What if I gave Blythe her own story? That way we could really understand why a girl would try to convince another girl not to report her rapist. All of a sudden, Blythe came through with her own story of sexual assault and her own problems and complexity. The book took on a whole new life then.

She’s the kind of girl who doesn’t realize how pretty she is. I can see it in her eyes. That scared look. One more oblivious girl who has no idea what’s coming to her.

—Hayley Krischer, Blythe in “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf”

Sometimes I wonder what it’s like to be her. In the hallway at school, she’s always staring straight ahead, like there’s a light at the end of the hall, or a camera, or else something else, much further away and superior. As if she’s looking anywhere other than here.

—Hayley Krischer, Ali in “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf”

DAVIDSON: While there are many personalities and overlapping friendships coursing through this novel—the Core Four of Blythe, Donnie, Suki, and Cate, and the trio of Ali, Sammi, and Raj, as well as friends Dev and Sean—the two central ones are Ali and Blythe. With the two quotations above in mind, tell us about the tangled relationships, to each other and beyond, of these high school girls.

KRISCHER: In many ways, Ali and Blythe are similar, and in other ways they’re extremely different. Blythe has been jaded for so long. First, she has serious issues with having a mother who is bi-polar and a father who is completely detached. Blythe’s whole life has been defined around her mother’s illness and what she doesn’t have. She’s jealous of Cate’s mother who is very loving. She’s jealous of Donnie’s mother who is very successful. She longs for a mother figure in her life, someone who can just be. Not someone she has to worry about all the time. Second, Blythe partook in this sexual “initiation” when she was only 14. Now she’s 17 going on 18. Her world has been filled with all kinds of trauma. So when she sees a girl like Ali—who seems oblivious—Blythe feels envious of it.

As for Ali, she sees Blythe as someone who is unreachable. Everyone does. She’s beautiful. Confident. People are afraid of her. That quote that you pulled starts out as Ali fantasizing about what a “popular” girl might think. That she’s staring into a camera. But Ali gets it more when she comes to the end of the paragraph: “As if she’s looking anywhere other than here.” That’s where Blythe wants to be. Anywhere, but here.

After Ali is raped, she detaches from herself as many rape or trauma victims do. She’s fascinated by Blythe because Blythe is so detached. Blythe doesn’t pepper her with questions. Blythe doesn’t expect anything from Ali, which is what Ali likes about her. And then a friendship starts to bloom. It’s a bit of a deranged friendship, but Ali likes that Blythe is messed up because Ali feels messed up too. It’s why Ali is able to stop talking to her best friend Sammi. Because Blythe’s detachment, while toxic, is also liberating. That way Ali doesn’t actually have to think of what’s happening to her, which is that she’s going through Post Traumatic Stress.

DAVIDSON: From classic literature to film—from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” to Olivia Wilde’s “Booksmart”—crowd scenes challenge writers and directors to navigate an enormous number of characters at once, while providing a specific perspective or lens through which to view the scenes. The shifting viewpoint between Blythe and Ali guides us through the party scene, deftly introducing each character and group of characters, and defining them by traits, attitudes, whispers and shouts. And then the structure swings hard. From chapter two and onward, Ali and Blythe’s viewpoints remain inside their own spaces, not shifting within chapters, but contained within them, separate and distinct. From here, there are closed doors upstairs, and the rape of Ali Greenleaf, and the aftermath that flies forward in each girl’s voice.

DAVIDSON: From classic literature to film—from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” to Olivia Wilde’s “Booksmart”—crowd scenes challenge writers and directors to navigate an enormous number of characters at once, while providing a specific perspective or lens through which to view the scenes. The shifting viewpoint between Blythe and Ali guides us through the party scene, deftly introducing each character and group of characters, and defining them by traits, attitudes, whispers and shouts. And then the structure swings hard. From chapter two and onward, Ali and Blythe’s viewpoints remain inside their own spaces, not shifting within chapters, but contained within them, separate and distinct. From here, there are closed doors upstairs, and the rape of Ali Greenleaf, and the aftermath that flies forward in each girl’s voice.

How did you decide on this structure and this entrance into the story, and what was the writing process like?

KRISCHER: The party scene, which is where the book starts, began as a much later chapter. I had written a lot of background scenes to start the novel originally. But as I kept doing revisions, and as other people kept reading it, everyone agreed that the book really started at the party. So I lobbed off the first few chapters. You have to be able to kill your darlings and see what operates for the book. The book needed to just START. I didn’t need to linger. I needed to linger in the middle and towards the end, as these girls began to understand themselves and act out because of their trauma. I think I also learned this trick in grad school. The first chapter usually gets cut. In my case, it was the first three.

Thoughts race in like thunder … how Sean had been so eager to be around me, touching me and whispering to me … Now I can’t help but wonder if he did all this to get to this moment. If he knew he had to get me on his side…

—Hayley Krischer, Blythe in “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf”

DAVIDSON: The idea of masculinity among teenage boys in the novel is approached within the environment of “conquests.” As the lead character in this high school world of sexual victories, Sean Nessel is envisioned as intriguing, the muscular soccer player with shoulder-length blond hair, and until the night of the party, Ali’s subject of infatuation. Sean’s manipulative, forceful, violent personality comes to the forefront quickly, while his best friend and Blythe’s boyfriend, Dev Strong, is revealed as compassionate and caring.

What are your thoughts about this kind of masculinity in terms of the novel and of the larger world?

KRISCHER: Toxic masculinity has been so pervasive for so many years! Look, I grew up in the ‘80s. Just take a look at some of the movies from that time and the girls are typically portrayed as objects without feelings and emotions, only to serve the needs of the teenage or college boy. Even “Sixteen Candles” is problematic. Jake Ryan! The hunk! The nice guy! He sent his drunk girlfriend off with a guy he didn’t even know, who didn’t even know how to drive, in his dad’s Bentley. I think the exact words are “I’ll give you my girlfriend.” For years and years, Jake Ryan was the “sensitive” guy everyone wanted. But then about five years ago, that started to change. It became cringy. Molly Ringwald wrote a great piece on it for The New Yorker. But there are so many examples. Endless examples of that kind of behavior where the man is somehow excused for being a perpetrator because his life matters more. Or that it’s so funny that a hot guy like Jake Ryan would give his bitchy girlfriend to a guy he doesn’t know and then that guy would have sex with her … even though she doesn’t remember the next morning. It’s unfathomable.

Anyway, I was a senior in high school when the Glen Ridge, N.J. rape case was in the news. (In an ironic twist, I currently live in Glen Ridge.) A group of high school athletes raped a low-functioning teenage girl in someone’s basement. They tried to cover it up. A person in charge came out and said, “Boys will be boys.” A girlfriend of one of the boys tried to get the girl to change her story. But the whole thing came out. A female detective (who is now our Chief of Police) kept on the story and the boys were arrested and went to jail. I grew up only a few towns away from Glen Ridge, and this was the kind of story that sticks in your mind. That you just don’t forget. It really changed how I looked at masculinity from an early age. That “boys will be boys” adage was so disturbing to me then. And it’s disturbing to me now. Despite the strides of the #MeToo Movement, we still have a very long way to go.

For five years all these girls—or maybe not all these girls?—are walking around traumatized, believing that somehow we could “deter” sexual assaults. That somehow we control the narrative.

—Hayley Krischer, Blythe in “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf”

DAVIDSON: Two different moments of sexual assault are addressed in “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf”: the nonconsensual violence against Ali and the bizarre, brutal manipulation against Blythe. As shown in the novel, these stories are important to expose, so that other young women know they are not alone, and how to protect themselves.

What led you to this subject, and how do you think this environment can be changed?

KRISCHER: Ali is definitely not alone, but she couldn’t have protected herself against Sean. They were having fun. She was drinking, yes. She was flirting, yes. She had a massive crush on this guy. And then he raped her. Blythe was manipulated not just by senior boys, but by senior girls who were convinced that they could take control of the sexual assault problem in their school by giving the boys “what they want.” Which was oral sex. She naively believed that if she chose to give a boy oral sex in a sterile environment, it would leave her in control.

So neither of the girls is the perfect victim, and I really wanted to delve into that area. We have so many stories about sexual assault. So many women and girls who are in these situations that aren’t so black and white. Ali was drinking too much. Blythe agreed to be there. But does that make them any less of a victim. No. Not at all. As a society we need to get out of our heads that a victim looks a certain way. No tight skirts. No makeup. No drinking. No desire. No flirting. No dancing. No talking. And guess what? Even if you follow all those rules, you can still get raped.

I really wanted to explore that idea of consent. There’s nothing either of the girls could have done to protect themselves. The boys on the other hand, if we had consent education across the country that really delved into what consent is, that’s the only way we can help our boys and help our girls.

DAVIDSON: In thinking of the last question, are there YA author/novel influences that led you to write “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf”?

KRISCHER: Of course, Laurie Halse Anderson’s “Speak.” Without “Speak,” there are no young adult sexual assault books. She opened the door for women and girls to talk about assault in YA literature. I’ve been very influenced by Megan Abbott’s books. Even though she’s a crime writer and I’m not, she takes on teenage girls with so much raw emotion that it pushed me to be that raw in my own work. And of course any books that dealt with teenagers and women in pain: “An Untamed State,” by Roxane Gay; “The Bell Jar” by Sylvia Plath; “Bastard Out of Carolina” by Dorothy Alison; “Birds of America” by Lorrie Moore; “Eleanor & Park” by Rainbow Rowell; “A Complicated Kindness” by Miriam Toews.

But I’m also drawn to the visual so there are a lot of movies about girls that have influenced me as well: “Little Darlings,” “Foxes,” “Heathers,” “Gas Food Lodging,” “Thirteen,” and yes, even “Maleficent.”

I want to be the girl who says what’s been done to me. To record my story. Without anyone holding my hand. Just me … My story. My words.

—Hayley Krischer, Ali in “Something Happened to Ali Greenleaf”

DAVIDSON: The way that Ali expresses herself by novel’s end is weighted in empowerment. She is direct, trying so hard to be strong, and every second of the final act of the novel, she is clearly stronger, through anger, insight, deep thinking, and the language she chooses to tell her story.

How do you see the process by which girls and young women can become empowered and hold onto the confidence and strength that ultimately could prevent violence against them?

KRISCHER: Again, prevention doesn’t have anything to do with girls or women. They can’t prevent it. Only men can. It’s about consent. We have to teach boys and men about consent. It’s about looking at your partner. It’s making sure your partner is “enthusiastically consenting.” It’s about being on the same level with your partner. Michaela Coel does an amazing job portraying all of the different layers of consent in her HBO series “I May Destroy You.” I highly recommend watching it.

As far as Ali’s empowerment. Yes, Ali is healing at the end of the story because she has control over the narrative. It’s not being done to her. She is making the choices.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor