How I Was Taught to Love:

An Interview with Eloisa Amezcua

by Karin Cecile Davidson

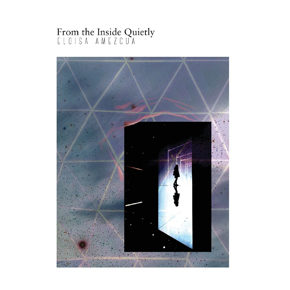

Eloisa Amezcua’s debut poetry collection, “From The Inside Quietly” (Shelterbelt Press, 2018), the inaugural winner of the Shelterbelt Poetry Prize selected by Ada Limón, cracks open the concepts of identity, language, perspective, persona, and voice with a blend of observation, confession, reflection, and a fierce gaze on the world. There is a curious lens in these poems that creates distance and, simultaneously, invitation. Observe, but don’t touch. Get closer, but understand, the universal leans toward what is specific, private, cautious.

Eloisa Amezcua’s debut poetry collection, “From The Inside Quietly” (Shelterbelt Press, 2018), the inaugural winner of the Shelterbelt Poetry Prize selected by Ada Limón, cracks open the concepts of identity, language, perspective, persona, and voice with a blend of observation, confession, reflection, and a fierce gaze on the world. There is a curious lens in these poems that creates distance and, simultaneously, invitation. Observe, but don’t touch. Get closer, but understand, the universal leans toward what is specific, private, cautious.

Originally from Arizona, Amezcua earned a BA in English from the University of San Diego and an MFA from Emerson College, as well as fellowships and scholarships from the MacDowell Colony, the Fine Arts Work Center, Vermont Studio Center, the Bread Loaf Translators’ Conference, and elsewhere. She is the author of three chapbooks and her second collection of poems, “Fighting is Like a Wife,” is forthcoming from Coffee House Press. A visiting faculty member for the Randolph College Low Residency MFA Program, founding editor-in-chief of “The Shallow Ends: A Journal of Poetry,” and Associate Poetry Editor at Honeysuckle Press, Amezcua is the founder of Costura Creative.

the world knows of her

what she does not know of herself—Eloisa Amezcua, “E Goes to the Museum”

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: In each of the four sections of “From the Inside Quietly,” there lives a delicate strength in the introductory series of the E poems. Introducing as well as anchoring the sections, the E poems lead us from childhood into adolescence into adulthood, each reflective of the voice—shy, confessional, achingly open—that guards them.

Eloisa, tell us about these poems, their placement and, therein, their implication.

ELOISA AMEZCUA: Originally, the “E” poems were mostly fragments I had in a word doc and I wasn’t too sure what to do with them when it came to compiling the manuscript. I picked out some favorite moments and shaped them into poems but then the poems became a real struggle in the editing process when put next to the other poems in the book. They went through many revisions from first person to second to third and back to first many times over. It wasn’t until I figured out the sequencing for the collection that I realized they could serve as anchors. I settled on third person—the book needed a speaker that wasn’t “I,” that functioned more of a birds-eye-view on E and served as premonitions for the poems that were to follow in the sections respectively.

This was how I was

taught to love:

to silence yourself

is to let the other in.—Eloisa Amezcua, “On Not Screaming”

DAVIDSON: Identity is recognized throughout the collection; women as bodies, silenced, “not a person, but a body is she.” “She,” “On Not Screaming,” “Boy,” “Autocorrect: No Sorrows,” and “Self-Portrait” vibrate with expectations and self-examinations of identity: “Call me what / you’d like; / in my own mind / I’m a mirror. / I see everything / except myself.” This theme is shared among the community of women poets. Ada Limon, Tracy K. Smith, Natasha Trethewey, Diannely Antigua, Megan Fernandes, Jenny Molberg, Kathryn Nuernberger, Paisley Rekdal, and Yolanda J. Franklin come to mind.

Speak to us of identity in these poems and of how you consider your creative role inside the collective realm of women poets.

AMEZCUA: I think the role of identity in my poems is largely rooted in the insecurities and self-consciousness that came from being a young girl who found herself in a woman’s body. I was over five feet tall with large breasts and curves in fifth grade. I noticed and observed the way boys, other girls, men, and women looked at me. And beyond that, I internalized what I thought those glances said about me, what they meant about the person I was and could be. I think this experience of being sexualized and objectified at a time when the brain isn’t capable of knowing what to do with that information is unique to female-bodied people. It shapes how we see ourselves and how we imagine ourselves in the eyes of those around us. I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to turn off that voice inside my head and I think I owe it to myself and other women/femme-identifying poets to put that voice down on the page.

DAVIDSON: Inside the series of poems about mothers and daughters lives a sense of duty, family history, disappointment, honor, burden, love, judgment, and belonging. “Teaching My Mother English Over the Phone,” “E Does Ballet,” “My Mother’s Been Trying to Kill Me Since the Day I Was Born,” “E Watches Mother Primp,” and “Waiting with My Mother in the Calimax Parking Lot” all reveal the bond and the binding complications of the mother-daughter relationship.

DAVIDSON: Inside the series of poems about mothers and daughters lives a sense of duty, family history, disappointment, honor, burden, love, judgment, and belonging. “Teaching My Mother English Over the Phone,” “E Does Ballet,” “My Mother’s Been Trying to Kill Me Since the Day I Was Born,” “E Watches Mother Primp,” and “Waiting with My Mother in the Calimax Parking Lot” all reveal the bond and the binding complications of the mother-daughter relationship.

How would you describe this relationship and the strength and frailty of the connection?

AMEZCUA: I think the relationship between a mother and daughter is extremely complicated. Thus far in my life, I’ve only been on one side of it (as a daughter) and I imagine being on the other end of it (as a mother who is also someone’s daughter) is even more difficult. Writing about this relationship wasn’t easy but I knew that in the writing process, in order to write the best poems I could, I had to be as hard on the speaker as I was on the mother-figure in the poems. I had to acknowledge and lean into the limitations of the speaker. For every poem in the book about a mother, a mother (my mother) has their version of that memory or experience or emotion.

careless undoers

untanglers of threads

we mend the frayed edges—Eloisa Amezcua, “Aubade”

DAVIDSON: In The Paris Review Spring 2019 Art of Poetry interview, Carl Phillips responded to a question about his “intensely lyrical” work: “I tell people … it’s okay to let the words wash over them, the way one experiences abstract art … I believe strongly in emotional and psychological narratives. I think of many of my poems as emotional gestures. Context isn’t always essential—or maybe it’s that I resist context as an absolute. I like what happens when context begins to wobble a bit.”

How would you respond to this with poems of “From the Inside Quietly” in mind: for example, “Incident,” “After Sylvia Plath,” “Self-Portrait,” “Suppose,” and “Aubade”?

AMEZCUA: I love this idea of poems as emotional gestures. Sometimes I hear a song or look at a painting and think I want to write a poem that makes someone feel the way I feel in this moment. And so it becomes a translation of emotion, of intensity. I’m not trying to mimic sound or image, but through sound and image, I hope to approximate a certain sensation or response. Those poems you mentioned are my attempts at translating feelings and less about describing moments or experiences.

I teach you Spanish

over the phone

calling that love, patient

when you confuse mouth

with tongue.

—Eloisa Amezcua, “Long Distance”

DAVIDSON: The connection and disconnection of language is explored in “Teaching My Mother English Over the Phone,” “Long Distance,” “Faint,” and “ Autocorrect: No Sorrows”. The difficulty of learning a foreign language, how teaching a new language is a form of love, that “sound does not translate meaning,” how there are multiple meanings to many words, how “nosotros” becomes “no sorrows”—all of these are approached, considered, examined.

Since the days of quarantine in spring 2020, have you begun to think of language differently? In terms of communication, creativity, conversation? Have connection and disconnection eroded or evolved in the way you think of language? In what you’re reading? And in what you’re writing?

AMEZCUA: This year. What else is there to say. This year has been so many things all at once. I didn’t know I could hold so many feelings simultaneously at a single moment in time.

My relationship with the production of language has changed a lot this year if for no other reason than I find myself unable to create language, or verbalize my thoughts and emotions and experiences right now, but still have an urge to create. This has shifted my work towards more visual places where I find myself attempting to evoke emotion through form instead of through content. My love for language has always been more rooted in the “how” than the “what” so I’m examining my own relationship to how I use words (on the page) and not what I am trying to say (because if I’m being honest, I never really know what I’m trying to say).

DAVIDSON: You have a collection of poetry coming out Spring 2022 from Coffee House Press. Tell us a little about “Fighting Is Like a Wife”—how it resembles or differs from your earlier work, what it reveals.

And ideas for the future? A hint for us of things to come, in terms of theme, fascination, or obsession? And also in terms of past and recent outcries for justice—the protests against police violence met with more police violence—and in terms of the Black Lives Matter movement?

AMEZCUA: The title “Fighting Is Like a Wife” comes from an article on two-time world boxing champion Bobby Chacon (the subject of my collection) written by Ralph Wiley for Sports Illustrated. When I finished “From the Inside Quietly,” I was tired of writing in the “I.” I wanted to move as far away from myself-as-speaker as possible. My parents were boxing fans and I grew up sneaking glances of the Pay-Per-View fights they would watch with their friends on Saturday nights. As an adult, I found myself drawn to boxing but more so to the stories of boxers’ lives—what lead them to boxing, what kept them fighting, why they would sacrifice their bodies in this particular way.

There is a longstanding relationship between boxing and poetry that goes back to ancient times and my hope is that this collection speaks to and expands that history to include Chacon who, like many boxers, had an extremely complex and often overlooked life and career both in and out of the ring. My obsession with Chacon stems not only from his life story, but also from his syntax. The phrase “fighting is like a wife” comes from a quote in the Wiley article. I remember reading it for the first time and thinking “THIS IS POETRY!” The book is an exploration of language, love, death, how all of those things are connected.

In terms of the future, I’ve had a difficult time these past few months thinking of anything beyond tomorrow or the day after. I feel like this pandemic and the ongoing visibility of protests against police violence have forced me to be hyper-aware of the present. I think looking too far into the future can begin to feel like escapism, like avoidance. Does my thinking too far ahead into an imagined future create harm in my present? Am I trying to absolve my past (and present) self of the ways I’ve perpetuated (am perpetuating) harm and violence by thinking things will just magically be better at some point in the future? Every day, I am trying to imagine a better now and hopefully a better tomorrow for myself and the people I love. It’s a daily task. And maybe all of these days together will eventually create a better future. But for now, I’m obsessed with the present.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor