Black Women, Front and Center:

An Interview with April Sunami

by Karin Cecile Davidson

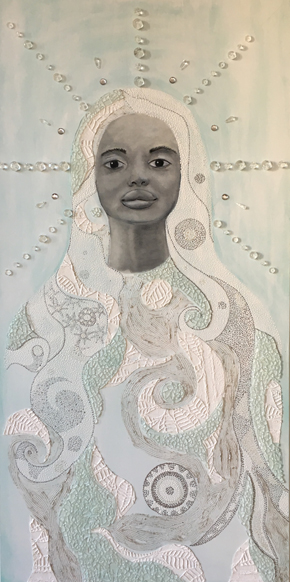

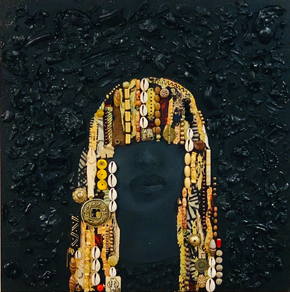

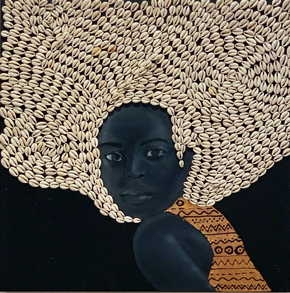

April Sunami conveys a warmth and generosity, a depth and brilliance that carry into her art. A visual artist, focused on mixed-media painting and installation, she is attentive to the world around her and to the world within. The palette she draws from is ever-expanding, whether in response to those nearest to her, the art community, or the greater Black Lives Matter movement. Her attention to black femininity and strength, and her use of oil and acrylic paints, textiles, maps, seashells, and shattered auto glass, create powerful and majestic works of art. From life-size canvases to diminutive studies, her paintings have a presence that calls forth, that summons and then demands consideration, reflection, and awe.

April Sunami conveys a warmth and generosity, a depth and brilliance that carry into her art. A visual artist, focused on mixed-media painting and installation, she is attentive to the world around her and to the world within. The palette she draws from is ever-expanding, whether in response to those nearest to her, the art community, or the greater Black Lives Matter movement. Her attention to black femininity and strength, and her use of oil and acrylic paints, textiles, maps, seashells, and shattered auto glass, create powerful and majestic works of art. From life-size canvases to diminutive studies, her paintings have a presence that calls forth, that summons and then demands consideration, reflection, and awe.

In Sunami’s own words:

For over a decade I have considered myself a cultural producer, contributing to the ongoing conversation of race, identity, and representation through the creation of paintings that place Black women front and center as the subject of my work. I deliberately create images of strong, spiritual women of color as a means of proclaiming my personal identity and providing a different lens for the social perception of black women. Many of my works are titled after West African queens and deities forgotten or ignored by Western historians. Through excavating these names, I feel I am remembering a marginalized past. It is also important to me that the woman is portrayed as an active and powerful subject instead of a passive object.

As a foundational base of my paintings I utilize oil and acrylic mediums. I render the faces and flesh in oil and I use acrylic to paint the ground palette of the body, clothes, and background. I build up the surface of my canvas and create texture by utilizing everything including paper beads, maps, wood, fabric, broken mirrors, bullets, stones, breakaway glass from car accidents, and anything else I acquire. Mostly these objects that I use in my paintings come to represent specific themes in my work such as spirituality, history, and mythology of the African diaspora, ancestral ties.

—April Sunami

Sunami earned her Master’s degree in Art History from Ohio University and her Bachelor’s degree from the Ohio State University. An award-winning installation artist through the 2012 Columbus Art Pop-Up Project sponsored by the Greater Columbus Arts Council, she has also been featured in various juried group exhibits, galleries and museums including the Columbus Museum of Art, the National African American Museum and Cultural Center, and a solo exhibit at the Southern Ohio Museum in Portsmouth, Ohio. Her art has been exhibited internationally, including at the National Theatre in Accra, Ghana, and in the Cuba Biennial exhibitions in Mantanzas. Her work is represented in private, corporate, and public collections throughout the country including Equitas Health, the King Arts Complex, and the Greater Columbus Convention Center.

Sunami teaches art to children in after-school programs in addition to serving as a resident artist in schools throughout Central Ohio. Sharing the joys of artistic expression with young people and creating collaborative work with her students and fellow artists is of utmost importance. She lives in Columbus, Ohio, with her husband, writer and philosopher Christopher Sunami, and their two bright and imaginative children.

KARIN CECILE DAVIDSON: Tell us about the women in your paintings. Their beauty, essence, and majesty suggest strength and stories. Speak to us, too, about scale, the process of creating larger than life-size images to small studies.

APRIL SUNAMI: My work is a corrective. I depict women to highlight the power they possess. To quote poet R.H. Sin, “She’s everything, even when she is treated like nothing.” Throughout history, women, especially black women, have borne the pain of giving life to both children and civilizations, and yet we are treated as secondary to men. In my work, women are primary; they are front and center; they are subjects with agency and power.

In terms of scale, I love to work at all sizes. Each allows for a different type of expression and each has its own specific challenges. I treat my smaller work as studies or experiments for the larger pieces that come later. Yet, the irony is that even the small pieces demand a lot of time.

“Make Your Peace II”

DAVIDSON: From the luxuriant colors and textures, to the central figures, your artwork is rich with messages and symbolism. What leads you to the utilization of such an array of materials? Cowrie shells, metal washers, lava beads, city maps cut into delicate lacework patterns, and so much more.

SUNAMI: My earliest paintings were done in oils. They can be toxic, however, so when I started my family, I switched to acrylics. It was a happy discovery that acrylics can be manipulated in many ways, which ultimately led to my exploring mixed media. At first, I just liked the challenge of seeing what could adhere to a surface. Later, however, I began finding deeper meaning in my materials. As I collected them from different sources, they came with stories attached. For example, my car was broken into twice. I ended up using it not only as a textural element, but also to tell a story about something broken and violated that was made whole again through my art.

Some materials have taken on a sacred symbolism to me. Whenever I utilize cowrie shells I’m referencing the African diaspora by way of the Middle Passage. Maps, in my work, are about a sense of place or the lack thereof. Other materials have been donated by friends and acquaintances. They all come with stories that get incorporated into the paintings.

“I create images of strong, spiritual women as a means of proclaiming my personal identity, and empowering marginalized voices.”

—April Sunami

DAVIDSON: Are there women in your life who influence the visions of your artwork?

SUNAMI: Definitely. I often use images of my friends as models in my work. My daughter and my nieces are also among my muses and I use their images a lot. I’m most inspired, however, by someone whose portrait I don’t paint often. My mother is my ultimate example of strength, empathy, beauty, generosity, and the kind of gentleness that exudes real power. She worked for 911 for nearly 40 years, as the person who people would talk to on the worst day of their life. She was the one who would talk them through life or death situations until help arrived. As serious as her work was, however, and as crazy as was her schedule, she always was there for me. She was our “room mother” all throughout elementary school. She carried around joy, pain, love, and humility at a level that I could never understand. That complexity and humanity is what I strive to bring to my subjects.

DAVIDSON: “Non Avere Paura II” arrives before us as an altar, a figure with whom to spend time, to pause and reflect, even pray. Are there moments of clarity that guide you to the spirituality so beautifully portrayed in many of your paintings?

SUNAMI: I consider my studio time sacred and guard it fiercely. My art is a spiritual practice. This is how I process things, and how I pray.

Seh Dong Hong Bey”

DAVIDSON: Funk and majesty, power and not at all aiming to please. All this, all at once. To me, these images have incredible personality, musical, defiant, curious, resistant. Tell us about this.

SUNAMI: In art, as in music, the most interesting work plays with contrasts and expectations. When I collect art, I’m most drawn to pieces that “hit me in the jaw.” As in funk music, there is something at a visceral level that you can feel physically. If I can achieve this in my own work, I will consider myself accomplished.

DAVIDSON: You’ve mentioned your grandmothers and family in Alabama. Are there stories and twists of memory that call to you from those relatives who inspire you to honor mothers and daughters, sisters, and aunts?

SUNAMI: Yes, my maternal grandma had so many stories about growing up in the rural South and living close to the land. I’m interested in exploring more of what her life was like, and learning about the complexities of what black womanhood meant in that time and place. My aunts, sisters, daughter, and nieces are the legacy of women who survived the Great Depression, Jim Crow, the Great Migration, redlining, wars, civil rights movements, and so much more.

Most of my work is a presentation of history, and less about personal narrative. I think, however, that may change soon.

DAVIDSON: The women and girls in your paintings have a presence that seems to arise from heritage and history and also comes across as contemporary. Within your process, do you have faces and narratives in mind? Is there a central image that you envision and create first, and how do you proceed from there?

SUNAMI: All of my work begins with a face. Whether someone I know or not, I have to feel a personal connection with the face. It becomes, for me, the embodiment of a historical figure, a feeling, or a state of being. In the Twi culture of Ghana, there is a term called Sankofa, which means, “Go back and get it.” This means that one must look to history to understand the future. Many artists within my circle have found our own ways to honor this concept in our work.

downtown Columbus, Ohio

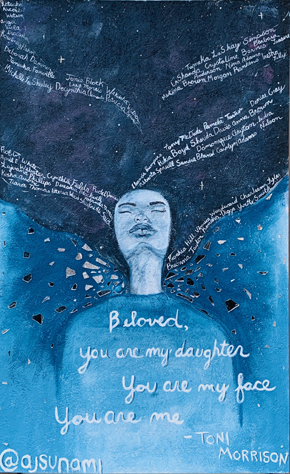

DAVIDSON: When I first viewed this #sayhername mural on social media, with its homage to Toni Morrison, its shattered mirror pieces flying from the figure’s upswept hair, the intertwined names of women taken from this world in violence, I imagined the image covering the entire side of a building. In reality, like the women to whom she pays tribute, she is life-sized, at street level, her eyes closed to onlookers, her face tilted to the heavens.

Tell us about the “Beloved” mural, and about the “Ella Baker” mural, how these figures came to you, about the art that bloomed on Columbus’s streets in response to the Black Lives Matter protests, in terms of community, our nation, the world, and in light of moving forward.

downtown Columbus, Ohio

SUNAMI: When the stay-at-home orders began, I was not motivated to create at all. My studio at the King Arts Complex was locked off, and I had set up a makeshift studio in my basement. To help ease my anxieties around the situation, I painted ten small abstract pieces.

It was around that time that deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd ignited the nation. At this point I knew artists were needed to be the eyes through which people would see the moment. Like so many others I felt overwhelmed by emotion. I felt infuriated, numb, sad, despairing, anxious, incredulous, and yet unsurprised. It was another senseless death at the hands of the entity sworn to “Serve and Protect.” This became the first time in months that I engaged with other people, and it was because I had something to say.

I wanted to highlight quotes from literature and the past. The “Ella Baker” mural was inspired by one of her most powerful quotes: “Until the killing of Black men, Black mother’s sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s son, we who believe in freedom cannot rest until that happens.” I thought about the tradition of social justice that grew out of the 60s, and how we can still lean on it today.

The other piece, “Beloved,” is a quote from author Toni Morrison. I felt that as an artist who exclusively portrays women as subjects, I needed to pay homage to the women and girls that have died at the hands of police. In essence, all of my work is about the women whom I see myself in, because I want them to be made visible.

Karin Cecile Davidson, Interviews Editor