That Sad Little Oboe

Note: Reading Mary Ruefle’s

‘Dunce’ on New Year’s Eve

A review by Amanda Rybin Koob

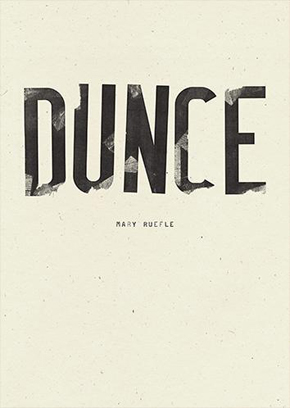

Mary Ruefle, “Dunce”

Wave Books, 2019

120 pages, hardcover, $25.00

What better way to enter 2020 than by already accepting my failures? I’m reading Mary Ruefle’s “Dunce,” and it helps: “at once I felt / there are so many years to fail / that to fail them all, one by one, / would give me a double life, / and I took it.”

What better way to enter 2020 than by already accepting my failures? I’m reading Mary Ruefle’s “Dunce,” and it helps: “at once I felt / there are so many years to fail / that to fail them all, one by one, / would give me a double life, / and I took it.”

This double life unfolds in multiple directions throughout Ruefle’s latest book of poetry. Or put another way, it is tempting to equate the double life with fake binaries that recur and dissolve in the book: memory and nothingness, companionship and isolation, life and death, love and loss. The absurdity of these doubles is key. In one poem, Ruefle poses these contemplations for Solomon: “Should he cut the baby in half / lengthwise or sidewise? // Each mum have an arm and a leg / or arms to one, legs to another?”

In the absurd there are satisfactions, small miraculous jokes: “Do you want I should make / some rapt contemplation / descending into useless particulars?” As for resolutions, next year I will probably try and fail to be something other than myself, then retreat back into my imagination: “Who won? I said. / The game’s tomorrow, he said. / And I became the snail I always was, / crossing the field in my helmet.”

In the world of “Dunce” there is always the taste of something dark, even in the poems that feel easy. In the opening poem, “Apple in Water”: “I was swimming / with the taste of apple / in my mouth / a shred of appleskin / between my teeth I guess / It doesn’t get any better than this / said the water / These are troubled times / said the shred.” And then other mundane moments are unexpectedly gutting. Fast-forward to “Halloween,” the fourth-to-last poem: “The corpse had a motion detector / and when you approached it / it sat up and stretched out its arms… / and then the most peculiar thing—it turned its head around… / then said something stupid… / and reminded me of my mother / and at the thought of my mother / there was a corpse in me.” Of course mothers continue to live somewhere.

Ruefle revels in simultaneity. Simple thoughts expand in puzzling or confounding ways, becoming strange as they layer, mummifying into some sort of bizarre papier-mâché. One of the only conclusions in the book is: “I am going to die.” And then: “No such thought has ever occurred to me / since the beginning of my exclusive time / in air when I, having made up my mind, first began to wrap it, slowly and continuously, / in strips of linen soaked in a special admixture / of rosewater, chicken fat, and pinecones / studded with cloves to stop them from dripping.”

The thought “I am going to die” must coexist with all in life that negates it. The rosewater, chicken fat, and pinecones. Lucky me: as a reader I have never been fond of conclusions. I invite all the other pleasures in when reading these poems, like looking up words to make sure I know their exact and double meanings (“lacuna,” “dunce,” and the Old English “warmship”), interrupting myself to re-read the work of other poets (Ruefle’s “The Butter Festival” reminding me of Andrea Cohen’s “Butter” and the saddest cow eyes imaginable), and searching for images and videos of the unfamiliar things Ruefle mentions (for example, a jewelweed pod, which I find on YouTube. A child’s hand touches it with reservation and then an adult voice says “perfect!” when it bursts, another adult saying plainly, “that was fun.”)

So much is bittersweet. Another double. My favorite poem in the book, “Maria and the Halls of Perish,” says: “And when her heart made / that sad little oboe note / she wanted to know where / the mind came from.” The mind in the poem remembers “the time / the toy factory blew up / and she found a little clown / on the shore, and then another, / until she was determined to find / them all, the whole shebang, / though she never did.” Determination breeds failure. In what world could we ever find all the clowns? There’s still something nagging my spirit to find one last Bozo under a rock.

Near the end of my reading, I flip to the bio on the dust jacket, and am reminded that Ruefle has long been an erasure artist. I’m tempted to say that reading this book of poems, maybe more than some of her others, is an experience that echoes reading her erasures. Not because “Dunce” refuses to be a rally against death, though it does. But because reading erasures requires belief in the blankness and delight in what discoveries are found there, which is also true of these poems. I disagree with my temptation, though, because “Dunce” is not even half blankness. It’s too full-to-the-brim for that. “Night falls / and the empty intimacy of the whole world / fills my heart to frothing.”

Here in this empty intimacy of the whole world, in our double lives, there are gnomes and cakes and berries and birds and diapers and rain, and pins held in the teeth, making a sound like rain. It might seem cute, and it is, and it isn’t. We are of it and apart from it.

Amanda Rybin Koob is a poet and librarian. She lives in Colorado.