Symphonies and Sweet Potatoes

John Linstrom

“L. Batàtas, Poir. Sweet potato. Creeping: leaves heart-shaped to triangular, usually

lobed: flowers (seldom seen) 3 or 4, light purple, funnel-form, 1½ in. long. Tropics;

grown for its large edible root-tubers.”

—L. H. Bailey, from “Botany: An Elementary Text for Schools” (1900), Second Edition,

1911, p. 380

▱

I used to kiss my grandmother goodnight. I’m not sure who started, my brother Ben or I, but one of us and then the other started going to bed regularly without kissing our parents because we thought we had outgrown it, and then, the next time we visited Elgin, Ill., to stay with our grandparents, we hugged Grandma and Grandpa goodnight without a kiss. I remember noticing Grandma furrow her eyebrows and Dad issue an apologetic explanation. And then my brothers and I walked off to the bunked beds upstairs.

The experience had always been strange. I’d purse up my lips into a tiny soft beak and press them into the adult’s larger beak, and then, in the awkward release, our lips would smack. It was a formal, not terribly sensual, intimacy. With Grandma, the kiss came with an over-the-top smile that she reserved for grandkids, and that we appreciated for its gratuitousness. Mom had never kissed them goodnight—she had rarely hugged her own parents growing up, let alone kissed them, so it wouldn’t have made sense with Dad’s parents. Dad continued to kiss his parents goodnight, despite the boycott Ben and I had begun, but he didn’t make Grandma smile the same way we did. And of course, it wasn’t long before Sam would discontinue the kisses and Dad was the only one.

▱

—From L. H. Bailey, “The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture” (1901), Vol. III,

1947, p. 3291

▱

I remember the Linstrom Thanksgivings like this. It happened every year. From separate satellite points scattered over the Midwest, we’d wake early, eat breakfasts calculated to fill without stuffing, and pull on buttoned shirts, black shoes. Nine o’clock church, with no lunch afterward. Our fathers would nervously hurry us to our minivans as we packed the old black bags; our mothers would put in a CD or change the radio. We would nap when we could. We would turn on our GameBoys, slap on our cheap headphones, try to draw shapes into the window’s condensation without our parents noticing. We’d leave marks. We’d smell the stale car-trip smell of the old Dodge Caravan, some combination of long-escaped French fries and the desiccated remains of lake water deep in the floor fabric, and remind each other, “Look out the front window. Don’t throw up.”

In our cars, we knew the landmarks. From the Caravan, Michigan’s frequent stands of maples, oaks, and cottonwoods would gradually thin. We’d pass the pair of cylindrical blue metal towers of the chemical plant with the strings of Christmas lights on top, descending conically from the antennae; the rust-belt fire-belching steel mills of Gary; the acrid smell when we opened the doors to use the McDonald’s restroom at the entrance to the Illinois Tollway. When we’d drive over the limestone quarry, gaping on either side of the freeway, we’d know we were getting close, and we’d compete to see who could spot the Sears Tower first. Dad would often take us through downtown Chicago, right past the base of Sears, and then the buildings would thin like the forests in Michigan, everything spread out and paved over, and eventually the one-car basket tollbooth that, after Dad appeased it with a toss of change from Mom’s purse, would spit us into Elgin, “The City in the Suburbs.”

Elgin meant Thanksgiving. It meant food—so much food consumed that fellow turkey-sedated relatives sometimes seemed to resent when Mom wanted to go for a run in the afternoon. It also meant the musty smell of the old basement, the scratchy carpeted floor over which we ran generations of Matchbox and Hot Wheels cars, some metal, some with opening doors. Elgin meant we’d go out for a movie later with our cousins, that we might stop at the Toys R Us on the way back home.

Elgin meant our grandparents, and our grandparents meant all of these things. They meant gatherings: the only time we saw our entire paternal family assembled. They meant power and continuity. Grandma would speak to us of symphonies—she had spent years working as executive director of the Elgin Symphony Orchestra, and she loved classical music—Grandpa would tell stories of the Nebraska farm and the Ogallala Aquifer, and they would reminisce about our father and his brothers as children. They told us they loved us, even though we only saw them a couple times a year. And somehow, they meant the words they said, the kisses they gave before bed. The house in Elgin swirled with signifiers that spun in the carpeted den and shot from eyes that tended to look like our own.

▱

“The sweet potato plant is a vine bearing purplish flowers like small morning-

glories. These flowers are not often produced in this country. The sweet potato is

probably native to tropical America, but its origin has not been traced. Some

authorities think that it does not occur truly wild, but has developed in the course

of centuries from another species.”

—L. H. Bailey, from “The School-Book of Farming: A Text for the

Elementary Schools, Homes and Clubs,” 1920, p. 195

▱

My grandmother died seven years ago, and the only electronic trace she left me was an email with a recipe. I never delete emails—I always archive them, keep them searchable—and of the twenty-some brief email conversations between my grandparents’ shared email address and my own, only one seems clearly written and signed by Grandma Linstrom.

November 17, 2008. I was a junior and studying abroad in Windhoek, Namibia. By November, homesickness had seeped into most of the twenty-two of us American students, so in a strange act of collective nostalgia we decided to throw the biggest Thanksgiving dinner of our lives in the packed house we had been sharing for months, a great potluck with each person taking responsibility for an iconic dish from our different families’ traditions. The starchy smells of baked mac and cheese and turkey stuffing would blend with the oily aroma of fried chicken and a tart-but-sweet undertone from the cranberries, we told ourselves as we planned it, the day after Halloween—in our minds we could each smell a certain room of a certain house, thousands of miles and a month away. A day and time had been set to meet in the living room to parse out responsibilities, and I remember being there early, sitting cross-legged on stiff carpet. I fidgeted, smashed the ends of my fingers into the carpet while others discussed logistics. As soon as the floor was open, I blurted.

“Sweet potatoes. I’ve got to do the sweet potatoes.”

Great-Grandma Ida Larson’s candied sweet potatoes. Her death represented a new kind of loss in my life when I was about nine years old. My memories of her house consist of three locations—the living room (with its toy closet), the seemingly exotic lattice-work archway in the small backyard, covered in roses, and the dining room/kitchen complex, for the two rooms seemed to share a certain kinetic energy, a mutual exchange of bustle. Great-Grandma Larson died at the age of 100, and she lived by herself in that house until the last couple months. She lorded over the living room, but the kitchen was her domain of glory—an old black-and-white photo that my dad took depicts her with a large fork lifted high above her head as she squints, her large nose pulled up between her eyes, at a massive, hanging sausage, the meat of which she had no doubt ground herself in the crank grinder bolted to the end of the counter. The smells of her kitchen I can’t recall distinctly, but they were domestic in the most comforting way; they emanated as if directly from the small, mysterious old Swede. She functioned as the symbol for me (engrained by my father’s devotion, no doubt) of wisdom and hard-to-catch wit. My father continues to evoke the memory of Grandma Larson every Christmas—whenever possible, our Swedish cooking recipes and techniques derive either from her kitchen or from one that lies beyond the reach of existing memory. Swedish meatballs, potato sausage, the doppa i gryten feast. After Grandma Linstrom’s death, the only one who could go back to the early days in Ida Larson’s kitchen was the surviving daughter, my Great-Aunt Lois, who survived her sister for several years in a nursing home. Eventually she stopped coming to Thanksgiving, her estranged children always far away. When she died a generation of Larsons ended. It was Lois who always brought the sweet potatoes to Thanksgiving throughout my early memory.

Thanksgiving sweet potatoes are not the first food that my family would want me sharing publicly. They’re not gourmet. They are treated differently than the rest of the dishes on the Thanksgiving table, most of which carry some representation on every adult’s plate, if not on every child’s. The turkey, which comes out of the kitchen in a pile of frayed, steaming strips, must be sampled by all—Grandma and Grandpa Linstrom have taken turns tending it all day, and it is understood to deserve respect. If it is tender to the point of falling apart, we praise the chefs at the far ends of the elongated table, all the leaves out (Grandma at the kitchen end of the dining room and Grandpa at the other end, halfway into the living room, with twenty or more of us in between); if it is a little tougher on a given year, we eat up gratefully. We comment less. We stifle children who complain, pretend it didn’t happen.

Then there is the stuffing, that curious and softly chewy, simple amalgam of ripped up bread, celery, and onion, which the turkey’s juice alone grants flavor. We do cook it in the bird, but we do not buy the premade packets. The cranberries are real, not the canned-jelly kind, and come from berry farms near my family’s home in southwestern Michigan, prepared with orange zest and juice by my mom, along with her small loaves of made-from-scratch fresh bread, baked the day before and heated in the oven before dinner so that they steam when you open them and the butter melts in seconds. As a rule, the cranberries’ tartness means they are eaten up by most adults and generally not touched by the younger kids. Mom’s rolls are always a hit. Someone brings green bean casserole, another brings a “fluff salad” that adds dubious nutrition and usually too much Jell-O. So the dishes travel around the table, hand to hand among as many as twenty of us, and we eat more than we need and then some.

At the end of the meal, out comes Grandma’s much-anticipated pumpkin pie. Everyone looks down to the end of the table where she sits, waiting for her to take the first bite.

“Oh, come on,” she’d say, turning her chin down and looking at us imploringly, and then, with mock-meekness and exasperation, taking her time and milking the moment for all it’s worth, she’d take the tiniest bite from the tip of her slice—and the meal’s final course would commence.

The sweet potatoes, though, are a point of pervasive contention. Among adults and kids alike, they have their detractors as well as their enthusiastic supporters—I would count myself and a number of the kids in the latter category. When Aunt Lois brought them, she followed her mother’s “candied” recipe, and candied meant sugar—and apparently lots of marshmallows. There are two layers to the dish, as experienced in the eating of it—the actual candied sweet potatoes, which form a sugary-sweet orangey semi-mush throughout most of the pan (but are not mashed, meaning the texture of the tuber remains), and then the layer of marshmallows, expanded and lightly browned over the top. Because the marshmallows melt slightly in the oven, they form a layer of chewy resistance that works well with the softness of the sweet potatoes below. My imagination loses itself in the warm, deep dish, swimming laps in the sugary syrup. The dessert-like quality of the whole thing will make some adults turn away, and the mushiness itself is a little too gross for some of the kids, but sweet potatoes have always been my absolute favorite Thanksgiving dish, and I have staunchly supported them through the years, taking much more than my fair portion to the objection of no one.

Eventually, however, something had to give. Over the past few years, my godparents, excellent and professional caterers from Wisconsin, have brought an alternative sweet potato dish, which involves a caramelized nut topping and possibly less sugar and butter. It’s great—probably an improvement—but it lacks the utterly sweet abandon of the old dish, the silly Scandinavian indulgence of simple staples, sugar and butter, and the strange postwar flair of marshmallows.

Sitting cross-legged in Namibia, I had never made them, but I figured they couldn’t be too hard; I thought I’d introduce Grandma Larson’s sweet potatoes to southern Africa. I emailed my grandparents later that week, and now my grandma’s response has become a sort of ethereal, electronic relic. She wrote it; the amazing thing in the age of the internet is that she clearly did not look it up on a website to copy and paste it—I’m not sure she would have known how to—and each fumbled letter refers back to her own fingers, at a time when they were warm and none too familiar with a computer keyboard. The details she may have looked up on a 3×5 note card somewhere, but I like to think she remembered them offhand, recording them in the language of cookbooks, of spells.

Hi John,

It has been so good to hear from you. We think of you often and are waiting to

hear about your months in Africa. We were just watching the Today Show on TV

and Ann Curry is with a group climbing Mt.Kilimangaro.

I’m feeling pretty good except for the coughing. I’m still taking tests but hope to

get going on the chemo soon. I still can’t believe this is really happening to me as

I feel good but now just hope they can get on top of it. We have a top of the line

lung specialist from Rush in Chicago so that should help. We’re looking 6orward

to Thanksgiving but wish you could be here too. I guess the best we can do is to

send you the Sweet Potato Recipe – good luck. Love you’ dear grandson.

Grandma

Candied Sweet Potatoes

6 medium Sweet Potatoes

1/3 cupmelted butter

1/2 te4aspoon salt

1 fup brownsugar

1/4 cup Water

Wash and cook sweet potatoes until tender. Peel and cut in halves length ways

and arrange in shallow pan or baking dish. Cover with the melted butter and a

syrup made by cooking the brown sugar and water together for five minutews.

Sprinkle with salt and bake in a slow oven 350 f. for 1 hour basting frequently.

The potatoes should be transparent when done. cover the top of the potatoes with

marshmallows and return to the oven until soft and slightly browned (short time).

▱

“What is a sweet potato? One is shown in Fig. 381. It has no ‘eyes’ or scales. It

produces roots. It is a thickened root.”

—L. H. Bailey, from “Lessons with Plants,” p. 363

▱

When a person dies, her body parts into so many organs, strung together by a little thread here and there and gathered tightly in a package—bundles of tendons, mysterious sinews. There’s not much there, certainly not quite what you recall, and you must again readjust yourself to what a body is, maybe give up guessing.

I would not understate a body’s legitimate power after death. There seems to be an aura that hangs around her still as you look down to the closed eyelids, the relaxed forehead. You recall her last words. You imagine how she’d react if she woke. Maybe you reach out and touch her cold forehead or kiss her one last time, and you feel that odd solidity that the dead carry, and you think, maybe there is something, maybe there is essence here still. But you must step politely aside, let the next mourner approach.

We’re never left with much. But we look for it. We finger through domestic relics, hoping to catch something; we poke around in little boxes, plastic photo sleeves, glowing screens. We bind up what’s left by bodies long buried. And later, we’ll need a little food, a little sleep.

Grandma’s hair—short, curly, and yellow—looked so perfect. She would spend some time every morning sitting in her burgundy leather La-Z-Boy with curlers in, which always seemed like a strange ritual to me. I’ve heard it said that she had to dye it to keep it yellow, that it had actually been white for some years. During the last year or so of her life, it became less common to see her with her hair done. At the funeral, the undertaker had done an impeccable job, we all agreed, getting Grandma’s hair the way she’d want it.

When I saw her in the casket, I did reach out and press her folded fingers with my own. Then, a little worried that no one else would (though they soon did), I leaned over and kissed her forehead. It was cold.

▱

“Propagation [of sweet potatoes] is mostly by means of ‘draws’ or ‘slips,’ which

are sprouts removed from the tubers. For this purpose the tubers are placed in a

bed (as a hotbed) and covered with loose earth. The slips are removed as they

grow and form roots. Two to four crops of slips may be taken from the tuber. The

tips of the young vines also make good cuttings, and the late or main crop may be

grown from them.”

—L. H. Bailey, from “The School-Book of Farming,” p. 198

▱

I like to remember my grandma’s sharpness of attention, the way she could zero in and focus all of her perception onto a single grandchild, erasing whatever uncertainties hovered around a room of extended family. Conversation she treated with all the concerted dignity of high drama. Sitting in my grandparents’ den with uncles, aunts, and cousins—on the couch, the extra folding chairs, the floor—someone might make a joke she found distasteful, about Beethoven, say, or Bach. She would work her face into a massive, over-exaggerated scowl and shake her head toward the ceiling, saying with breathless emphasis, “I don’t know how, but this is the family I raised …” An uncle might then try to throw a joking comeback, but Grandma wouldn’t acknowledge it. She’d flip her expression upside-down into a beaming grin, hunch her shoulders as if trying to make a secretive aside, and whisper, “At least my grandkids came out okay,” making eye contact with each of us in turn. It was as if no one else had said anything worth hearing. She had an impressive ability to make certain people feel important, but more than that, I think she knew that we felt excluded from the adult-dominated conversation, and she was the one who always made an effort to bring us in to a special inner circle, with her, one in which none of our parents were quite allowed.

She was a powerful woman, a strong-built Swede who spoke her mind, but I think the very locus of her power may have been in her famous “Linstrom Nose” (technically, of course, a Larson nose). Aside from occasionally scrunching it up into an expression of mock-disgust, her nose served generally as the solid resting-place around which her elastic facial features danced. And it held considerable prominence, a solid inch-and-a-half’s worth. She would pass the Linstrom Nose on to all four of her sons, and with it, uncanny powers of olfactory perception. Without fail, when the Linstrom Nose comes into conversation, my father will recall the day he and his brother Tim snuck a bag of forbidden potato chips from the snack closet when they were kids. They were sitting in the den when they heard their mother unlocking the door. My dad flung the bag under the couch well before the door creaked open. It reportedly did not take Grandma more than one step into the house before she boomed, “Who’s been eating potato chips?” Hers had always been the archetype of the Linstrom Nose, the first that we knew of and the greatest. A regal nose, as my father sometimes describes it (to my mother’s amusement); it seems to have skipped my generation altogether.

I flipped through a few photos of myself the other day, looking for traces of Grandma in my face. If I look carefully, I can see a similar sharpness to the contours of my eyebrows—mine are lighter, though, and fade into my forehead more. The mouth seems to bear some similarity, but I think it has more to do with the alacrity of my cheeks and forehead, the quick transitions between expressions. Maybe that’s what I inherited: something about the movement of muscle between the pictures, the ability to express thoughts and emotions in rapid succession. It’s not solid, not definable—it’s intangible, nebulous, somehow marginal. In my case, it leads to a lot of bad photos, mid-expression misses. But that Linstrom Nose, that rudder of purposeful directness with which she could command and navigate the emotions of a room, I certainly lack.

▱

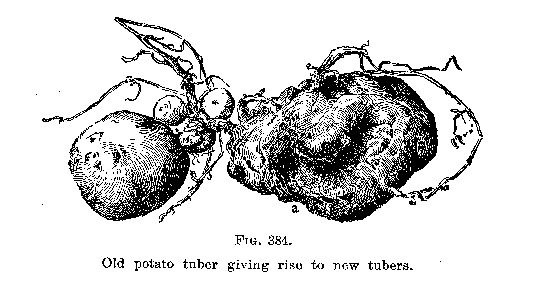

“A forcible illustration of the fact that bulbs, corms, tubers, and the like are

storehouses of plant-food is suggested by Fig. 384. This represents an old potato

tuber (a), from which new tubers have grown, while it was still in the bin. This is

a frequent occurrence in potato bins in which there are tubers a year or so old. The

tuber endeavors to grow, but finding neither light nor soil, it makes new tubers out

of its own substance.”

—L. H. Bailey, from “Lessons with Plants,” pp. 365-6

▱

I heard about the cancer over the phone, in one of my weekly international calls in Namibia. My only phone connection to the States was the landline in the kitchen, so I heard about it while surrounded by people who were walking around, chatting, eating. That memory is completely blank; I don’t remember what was said or by whom. I believe I slumped against the wall. I remember “thyroid.” “Advanced.”

We didn’t know until later, still during my semester in Namibia, that it was actually metastasized stage 4 lung cancer that had spread to the thyroid. I remember the absolute despair. I remember imagining the black tendrils reaching through her—Grandma, my grandma, the strong one, in the grips of some unfair curse of nature, eating her from the inside. She had never smoked, never lived with a smoker. She wouldn’t have tolerated such behavior. I wanted to reach into her and rip out those evil choking fingers in her lungs, bite them out with my teeth, swallow the mash down sweetly, take part of the load. I wanted to choke.

At some point after I hung up, I found myself in the compound’s library, a small shed disconnected from the house where we were staying. I stepped up to a built-in bookshelf that was at about waist-height. I remember breathing heavily, swinging my head. I gripped the shelf with my fingers and heaved up, with all the strength of my legs and back, and snapped the shelf from the nails that held it down. My fingers blistered, and white paint stuck to them in patches. Slowly, I began to cry.

▱

“Sweet-Potato. BLACK-ROT (Ceratocystis fimbriata, Ell. & Hals.).—A dry-rot

of the tuber, and a black rust upon the stems. Upon the tuber it appears in

large scab-like patches, and is usually evident at digging time. It may

appear upon the young plants in the hotbed and persist upon them

throughout the season.

Remedies.—Rotation of crops. Spray the young plants, if attack is feared,

with copper fungicides.

DRY-ROT (Phoma Batatæ, Ell. & Hals.).—The upper end of the tuber becomes

dry and wrinkled and bears a multitude of pimples, and its flesh becomes

dry and powdery.

Preventative. —Destroy all affected tubers.

LEAF-BLIGHT (Phyllosticta bataticola, E. & M.).—Produces white, dead

patches upon the leaves.

Remedy.—Spray with some of the copper fungicides.

SCURF (Monilochætes nigricans, Ehr.).—The tubers rot with a soft and putrid

decay. It is most destructive after the potatoes are stored.

Preventatives.—Store in a well-ventilated, artificially warmed room, at a

temperature of about 70°. Store only sound and perfect tubers, and remove

at once any which are attacked.

[etc.]”

—L. H. Bailey, from “The Horticulturist’s Rule-Book: A Compendium of

Useful Information for Fruit-Growers, Truck-Gardeners, Florists, and

Others,” New and Revised Edition, 1898, pp. 73-4

▱

Grandma struggled with the cancer for about two years, with about a year’s good remission; in the spring semester of 2011, my first year in graduate school, I got another call from my father, this time on my cell phone as I sat in my girlfriend’s apartment in central Iowa. Dad sounded tired. “Your grandma’s taken a turn for the worse,” he said. “She’s in a lot of pain, and Grandpa’s driving her to Rush. It’s hard to know whether she’ll make it through the week. You might want to make it over here this weekend.”

It was Friday afternoon. I considered briefly the pile of fifty-two student papers I had to grade for the two composition classes I was teaching, and the couple books I needed to read for my own graduate classes. “Okay, I’ll be there,” I said.

I told my girlfriend Rachael I was going, and she told me she’d go too. She started boiling eggs and gathering other food for the road while I tried to figure out how much work I’d need to bring with me and looked up directions. I had never driven from Ames to Elgin before. The week before, I had visited my grandparents on the way to Ames from my hometown in Michigan.

On that visit, when I walked into the den with Grandpa, Grandma sat in her burgundy leather La-Z-Boy, as she always had since I’d been alive, and she stood up to hug me when I walked in. Grandpa sat down in his blue leather La-Z-Boy, just on the other side of the end table from Grandma, as he always did. I sat on the couch across from them and asked how she was doing. Her hair gave her a frazzled look; it was generally reined-in and combed, but not curled, and little tufts sprouted out here and there, signs of where her fingers had run. A machine stood against one wall, from which a plastic tube descended into a pile on the floor that trailed to Grandma’s chair and ended around the back of her neck and into her nose. The machine whirred constantly and sent a regular pissh of air every couple of seconds. She was not fond of it, and her smile flipped into a scowl when she spoke of it.

“It makes me feel so weak,” she said. “I don’t feel bad, mostly—but I hate being connected to this tube all the time—I really don’t think I need it! But I don’t know what I’m doing wrong … it seems like I should be getting better, but then I go and get these reports, and Dr. Benomi—he’s wonderful—but I just don’t want to go back. I don’t want to hear about what’s wrong anymore—can’t they tell me something good?”

We reminded her that she had gotten a lot of good reports from the doctors, that she was doing exceptionally well for someone her age (you’re a fighter, we’d always remind her, the words increasingly desperate). This was just another rough spot between remissions.

“I don’t want another rough spot.”

Later in the visit, Grandma needed to lie down in my Uncle Steve’s bedroom, just off from the den. She could only maintain a sitting position for so long before it became too painful. Grandpa went to fix some food in the kitchen, so I stuck around in the bedroom and talked with Grandma. She apologized for not being a better host, and I told her she was being silly. The oxygen machine pished along.

Eventually her experiences with the MRI came up in conversation. “I just hate going in there,” she told me. She furrowed her brows and shook her head while she described it, not making eye contact. “It’s so noisy … They send you down this tunnel, and it’s cold, and the noise, like so much crazy metal spinning all around you …” It wasn’t how she normally talked, not how one typically talks, and the poetry of it scared me. She trailed off and looked back at me. “I hate it.”

Grandma and Grandpa sent me on my way with a box of cookies they hadn’t made. They were a gift from friends of the family, probably church members from the parish where Grandpa served as pastor. I didn’t eat any on the road. Instead, I plugged in my MP3 player and switched to Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony,” a favorite of Grandma’s. The first movement is full of descending lines, culminating in a driving, incessant downward motif from the basses that made me think of crevices opening in the frozen Illinois countryside, the whole state slipping into them like a tablecloth. I gripped the wheel hard, imagined cornstalks vanishing downward into the crevices. The first gives way to a more fevered movement, which Beethoven labeled molto vivace, a tempo marking that I remembered in my childhood piano teacher’s translation: “much life.” The sky was the cold gray of brittle January, and I wondered at the two-year-long holding pattern that our family had been in. Two Thanksgivings before, while I was absent and across the world in Namibia, Grandma had announced to the family from the head of the dinner table that it was her last Thanksgiving. After that she went into a long remission, and many of us stopped thinking about her temporality. It seemed like she was beating it, although we all knew that was statistically impossible.

The third movement of Beethoven’s symphony is the slowest—adagio molto e cantabile, indicating “much slow smoothness and a singing quality.” It struck me then as strangely out of place after the previous, more torturous movements, slowly building over the course of 20 minutes into a long climactic swell that then slowly fades again into a soft warbling. The clouds over Illinois parted early in the movement, and I watched them move, letting down sun rays onto the cracked farmland where I had envisioned cataclysmic fissures. Then the final movement, split into four different tempo sections, vacillating constantly at first between major and minor keys, revealing snatches of its famous melody tune bit by bit until it finally takes over, and the symphony culminates by breaking, for the first time, into sung poetry, the choir emerging from the texture like wheat bursting into the air—“Ode an die Freude,” Ode to Joy.

▱

—From “Cyclopedia of American Agriculture: A Popular Survey of

Agricultural Conditions, Practices and Ideals in the United States and

Canada,” edited by L. H. Bailey, Vol. II—Crops, 1907, p. 619

▱

The weekend that I got the call from Dad, Rachael accompanied me to Illinois. She would accompany me again, the following weekend, for the funeral.

Grandma looked small and baggy. In her hospital gown, we could see how the skin sagged away from the bones in her arms when she lifted them to hug us. Sometimes she seemed aware of everyone in the room, but typically she’d focus on one person at a time if she wasn’t lost in another morphine-induced nap. When she had to move, she’d scrunch her brow and go wide-eyed in pain. We would take turns feeding her ice cubes with a spoon, as her appetite for anything but hydration dwindled. At one point she asked for music, so Sam went and found his headphones, connected them to Rachael’s iPod, and set them on the pillow next to Grandma’s head. She could hear George Winston’s soft piano playing, an album called “December” set on repeat, as she slipped in and out of our conversations.

Only a certain number of people were allowed in the room at a time, so family members would come and go, sometimes hanging out in the lounge or the hallway talking about what we were all up to, as if nothing were different. One time I remember standing next to Grandma’s bed with only a couple of other people in the room, gently wiping her forehead with a damp washcloth to cool her. Her hair stuck out in every direction, and this made it worse, but she didn’t seem to care anymore. I wasn’t sure how to describe to Rachael how different she was. They had not met before. When I introduced them and told Grandma that this was the Rachael I had told her about, Grandma reached out and hugged her and said, “Oh, she’s so beautiful.”

The family spent that night at the house in Elgin, sleeping in guest beds, on air mattresses, on the basement floor, and on couches. In the morning, we left at different times by the carful to head back to Rush Hospital in Chicago, where we repeated the ritual of the night before. Rachael and I had a six-hour drive ahead of us, so we were the first to leave that afternoon. I hugged my grandmother and told her I hoped to see her again soon. She shook her head and said, “I don’t think so.” Then I leaned forward and kissed her, like I did as a child, a shy Scandinavian peck on the lips. She smiled, gripping my hand hard, and said, staring straight at me, “Don’t get into trouble.”

▱

“Here is the whole philosophy of the contented festival,—the fruit of one’s labor,

the common genuine materials, and the cheer of the family fireside. The day is to

be given over to the spirit of the celebration; every common object will glow with

a new consecration, and everything will be good,—even the mustard will be good

withal.”

—L. H. Bailey, from “The Holy Earth” (1915), 2015, p. 62

▱

After Grandma died that February, I worried about our next Thanksgiving. She had always been the axis of the event, seated during the meal at the head of the table nearest the kitchen, partially to allow her to get up and pass around another set of seconds or thirds or fourths whenever the spirit moved her. She linked us directly to Great-Grandma Ida Larson’s recipes and traditions. She maintained the sweet potato recipe, and she made the pumpkin pie.

When Thanksgiving finally came, we were a small group. Two family clusters could not make it, but the thirteen of us who were there managed to prepare all the traditional food. The table was set as Grandma had always set it, with the old china and silver. We did not leave a gap at the end of the table, which I had feared. Grandpa sat in Grandma’s place. He stood and said a few words before the meal, emphasizing how fortunate we were to be together and how blessed he felt. He said he knew that Marcene’s influence was guiding him. His voice was shaky and his eyes wet, but when he sat down Uncle David and my cousin Victoria got up and immediately began passing the food. Their action relieved the rest of us.

Cranberries, rolls, stuffing, corn pudding, and asparagus all made the rounds. The turkey was especially tender, we agreed. David and Heather did the cinnamon-nut version of the sweet potatoes, which met with great approbation, but we remembered the marshmallow recipe in passing and laughed a bit about how several of us missed it.

If I were to make more of Grandma’s absence that year, I might be lying. Everyone, of course, felt it. Conversations sometimes lagged when she might have picked them up. Our banter occasionally picked up a sense of formality and sometimes felt a little less dramatic and fun. Her magnetic presence may not have lured us into the den between meals to enjoy each other’s company, but her absence did, as well as our heightened concern for each other. Our own “Ode an die Freude” filled the fissures in the house’s landscape. Our best moments that year, though, were the ones when we did not try particularly hard to compensate for the loss, but simply did what we knew to do. They were not moments of innovation or especially emotive expression. The kinetic energy that had been set in motion decades, generations, in some cases centuries before, had been intentionally directed to adapt to these tragedies. I envisioned the dramatic shift the family must have felt when they stopped having Thanksgiving at Grandma Larson’s house, years before my time, and moved into my grandparents’ house, back when my dad was young. I thought about those Linstroms and Larsons I had never met, and their parents dying, their shifting of tradition. I wondered who first began making those candied sweet potatoes.

Much of the three-day reunion’s success had to do with certain family members’ specific efforts to make it go as smoothly as possible. Over the phone, in the months preceding the gathering, Grandpa impressed upon his sons that we would do everything as it had always been done. He reorganized the den, moved the two upholstered leather chairs away from the wall where they had always stood and set them at angles on opposite sides of the room. Different people filed through them over the several days we were there. Those chairs were the only things that had become less sacred, or differently so. The chairs, and maybe the sweet potatoes.

Grandpa took his seat in Grandma’s old place at the table. At the end of the meal, after we passed around the pumpkin pie (which my godparents replicated beautifully with same recipes Grandma used to combine), a couple people started whispering. “Don’t touch the pie!” one younger cousin scolded another. “Grandpa gets the first bite!”

When Grandpa stepped in again from the kitchen and sat down, we all looked toward him. I worried that this would be another difficult speech. The room was silent for a moment. “Many of the tasks that fall to me are difficult responsibilities,” he began, and lifted up a corner of pie on his fork. “This, however, is not one of them.” He smiled, and we laughed as he lifted the bite to his mouth.

▱

—From “Cyclopedia of American Agriculture,” p. 613

John Linstrom’s poetry has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Cold Mountain Review, Vallum, Atlanta Review, Writers Resist, and Valparaiso Poetry Review, and his nonfiction was included in “Prairie Gold: An Anthology of the American Heartland.” He is series editor of The Liberty Hyde Bailey Library for Cornell University Press, and is currently a doctoral candidate in English and American Literature at New York University.

John Linstrom’s poetry has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Cold Mountain Review, Vallum, Atlanta Review, Writers Resist, and Valparaiso Poetry Review, and his nonfiction was included in “Prairie Gold: An Anthology of the American Heartland.” He is series editor of The Liberty Hyde Bailey Library for Cornell University Press, and is currently a doctoral candidate in English and American Literature at New York University.